Mapping and Analytics

Wisconsin’s Oak Leaf Trail | Photo by Ken Mattison

RTC’s TrailNation™ Playbook curates case studies, best practices and tools to accelerate trail network development nationwide. Explore each section for lessons learned that can support trail planners, municipalities, states and regions working to advance trail network projects.

Project Vision | Coalition Building | Mapping and Analytics | Gap-Filling Strategy | Investment Strategy | Engagement

Developing and maintaining a geospatial dataset that identifies open trails as well as undeveloped segments—or gaps—is critical to understanding the scope of a trail network. Ultimately, this process allows a coalition to define the trail network based on its collective vision. By analyzing this geospatial data, coalitions can map the current status of the network and project its future evolution and growth. This is a fundamental step in prioritizing projects within the network and developing an implementation plan that will accelerate trail network completion. It is also a powerful tool in building political and public support for a trail network vision, aligning projects with funding opportunities, and understanding the potential economic and social impacts of the trail network.

Mapping to Define the Trail Network

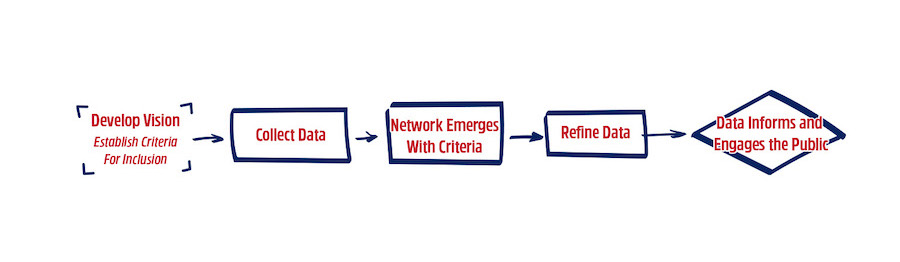

Mapping is the process of gathering, analyzing, refining and maintaining geospatial data so that it visualizes the scope of a trail network and provides direction for prioritizing projects and targeting investment over time. Leveraging data to understand the relationship between the trail network and the people it serves can be powerful for elevating disparities in trail access and building a trail network strategy that emphasizes equity and inclusion. The process to map a trail network begins with establishing criteria, followed by a comprehensive and collaborative data collection process, analysis of the emerging trail network, data refinement and maintenance, and finally leveraging the data visualizations and mapping tools for public and political engagement (Figure 1).

Developing Criteria for Trail Network Inclusion

Through the visioning process, coalition members begin to define desired characteristics of trails that will comprise the network as well as features of the network itself (e.g., interconnectedness, ease of access to community assets and destinations, or other local priorities). These characteristics and features, or “attributes,” should be established early on as a set of criteria for including an open or planned trail as part of the trail network.

Criteria may include considerations for:

- Geographic boundaries, the trail network footprint, or “trailshed”

- Trail use and surface types

- Connections to other bicycle and pedestrian facilities

- Connections to other open-space assets or networks such as parks, beaches, greenway, etc.

- Social and demographic data

- Timeliness of ongoing trail projects and existing planning work

- Topography

- Property ownership status and land-use zoning

Developing criteria for inclusion in the trail network may be especially useful for regional trail visions that include multiple jurisdictions that have not formally collaborated on connecting trails between their municipal, county or other regional boundaries. This process can provide additional focus for a newly formed collaboration and can help ensure early buy-in from partners.

One example can be seen in the Capital Trail Coalition, which is working to establish a regional trail network in the Washington, D.C., metro area. The coalition’s criteria for network inclusion was initially used to identify which of the hundreds of trails within the region would be included in a trail network that reflects the coalition’s vision of a “world-class network of multi-use trails that are equitably distributed throughout the Washington D.C. metropolitan region.” Now, the criteria serve as a decision-making tool, guiding the integration of existing and planned trails as the network evolves.

Lessons Learned

Developing network criteria for trail network inclusion can provide focus for coalitions as they set goals. Eventually, the criteria can also aid in the process of gap filling.

The process of mapping and analytics brings the trail network vision to life. Mapping demonstrates what the vision will achieve, and analytics helps inform decision-making by demonstrating why the vision is important—a clearly defined vision is essential to creating the criteria for network inclusion.

Data Collection and GIS

After the coalition establishes criteria for including existing and planned trails in the network, gathering existing and planned trail data from within the defined footprint will be the first step in creating a trail network map and GIS (geographic information systems) dataset.

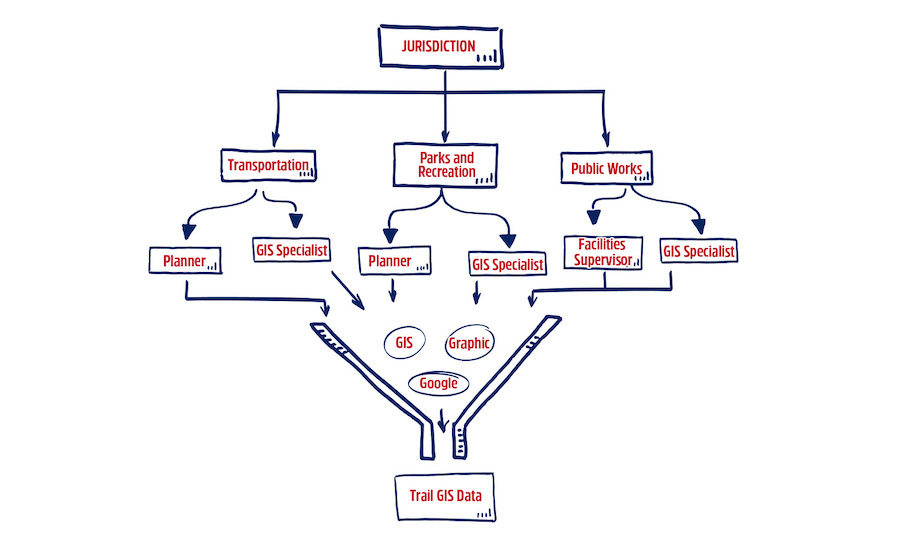

This process will require the input of many individuals within the coalition and communities the trail network serves. For trail networks that extend across multiple jurisdictions, engaging relevant planning and GIS staff from each jurisdiction to discuss existing trail plans, maps and data will yield more comprehensive outcomes. These initial discussions will help members of the coalition (who may also be staff or representatives of the jurisdictions) begin a conversation around the culture of trail planning and development, establish relationships between the jurisdictions and the coalition, and begin a discussion about which data will provide helpful metrics to track the success and impact of the trail network (e.g., trail user counts, safety and crash data, etc.).

Metropolitan Planning Organizations (MPOs) and Trail Network Planning

In many regions, the Metropolitan Planning Organization may lead or support regional trail planning and will be the best entity to collect trail data and develop the trail network GIS and mapping.

In the Greater Philadelphia region, for instance, the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission (DVRPC) has partnered with a coalition of dozens of organizations and agencies, including Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC), to develop and manage the mapping for the Circuit Trails, a planned 800-mile network of multiuse trails in the region. In addition, DVRPC leverages its unique structure and large professional staff to help ground the coalition’s work in policy, build political will and source funding.

This collaboration between multiple jurisdictions may seem intuitive, but often silos exist between neighboring jurisdictions and even between agencies within the same jurisdiction. Trail planners, trail network coalitions and advocates are in a unique position to help improve collaboration in pursuit of shared goals for the trail network. Setting up data-sharing agreements or even regular check-ins on geospatial data updates and cross-jurisdictional initiatives are strategies that can help advance trail network collaboration.

Collecting trail data from multiple jurisdictions and distilling it into a single regional trail network dataset may be challenging. The process will take time and coordination for a trail network that spans several jurisdictions. Even in a single jurisdiction, the input of many individuals and partners can be needed to flesh out a comprehensive dataset (Figure 2). There are common elements that factor into the complications of data collection. For example, a comprehensive and authoritative dataset or layer for trails may not exist for each jurisdiction. Data may exist in various forms (e.g., as a part of bicycle facilities GIS data) and in various locations (e.g., county parks department, planning department). In addition, there may not be consistency or standards for collecting trail data across a region, or even across agencies within a single jurisdiction. A jurisdiction’s transportation agency might include certain types of trail facilities in its plans and data, while the parks and recreation department might include other types of trails that also meet the criteria for trail network inclusion.

A thorough “plan review” for trails at the local, regional and state levels may also be a necessary exercise as part of the data collection and mapping process. Planning documents may include:

- Comprehensive plans

- City, county or regional bicycle, pedestrian and trail master plans

- Long-range transportation plans

- Business improvement district plans

- Multimodal transportation plans for a single corridor

- Jurisdictional, regional or statewide bicycle or trail plans

- Tourism strategic plans

- Parks and recreation master plans

Referring to authoritative, publicly approved plans will help identify where to access GIS data, which public agency staff may need to be involved in the mapping process and how certain planned trail projects are being prioritized. Including trail projects from publicly approved plans (perhaps as part of the effort to define the criteria for trail network inclusion) may also ensure some level of community engagement and public input, although this will vary greatly from plan to plan. Community engagement will need to be prioritized during the mapping process, especially if the trail network is not largely derived from plans that included strong, equitable planning practices.

Lessons Learned

Bringing many stakeholders together to map the trail network helps build and strengthen the trail coalition by encouraging collaboration across jurisdictions and across agencies and departments within jurisdictions. Plan to meet one-on-one with each jurisdiction and include different agencies that may be responsible for GIS data and trail management. Build time into the process for jurisdictions to meet among themselves before and during the process to address discrepancies in data and priorities that are likely to emerge.

Visiting corridor gaps with local partners and ground truthing the information being collected is an important data-gathering exercise. This process can also help with advocacy and coalition building, providing an opportunity to explore the project’s exciting possibilities.

Recognize that this is a highly skilled exercise, and ensure that GIS expertise exists to manage the process. It is useful to have access to cloud-based mapping software such as ArcGIS Online, which provides a suite of tools for shared data collection, map creation and data-driven storytelling to promote the trail network vision.

Analyzing and Visualizing the Emerging Trail Network

Once comprehensive data collection is complete, use the criteria for trail network inclusion to filter the data. This may occur as a series of spatial data queries that help identify which trails meet the criteria and should be included as part of the network. For example, if trail interconnectivity is a criterion, then any open or project trails that do not connect to another trail or trails within the network footprint would be excluded. Filtering the data with other criteria, such as trail surface type, trail width or other factors, may require a visual analysis via aerial imagery or on-site investigation. It may also call for additional consultation with the jurisdiction’s managing agencies to understand factors that are more difficult to visualize or quantify, such as understanding what uses are permitted on the trail.

After the data is filtered and a draft of the trail network emerges, verify with the key partners and local jurisdiction agency staff that the trails included in the final-draft trail network layer are appropriate. If available to partners, using an ArcGIS Online web application to edit trail data and information can be an effective way to capture feedback and make changes in real time during face-to-face and virtual meetings.

A final trail network layer can be used to promote the regional trail network vision and to encourage support and investment for completing planned segments or filling gaps within the network. Many coalitions use a combination of online, interactive maps as well as graphic maps to help decision-makers and the public understand the regional impact and community benefits of being connected by a robust trail network. An accurate spatial dataset will be the foundation for analytics that will help communicate the vision and build momentum to advance its progress.

TrailNation

Through the TrailNation initiative, RTC works in close partnership with dozens of local, regional, and state governments and organizations to lead or support the visioning and mapping phases for several regional trail networks across the country. These online, interactive maps and graphic maps are examples of ways GIS data can be visualized to bring the trail network vision to life.

- Baltimore Greenway Trails Network: MD

- Bay Area Trails Collaborative: CA

- Capital Trails Network: MD, VA, DC

- Caracara Trails: TX

- Circuit Trails: PA, NJ

- Great American Rail-Trail: DC, MD, PA, WV, OH, IN, IL, IA, NE, WY, MT, ID, WA

- Industrial Heartlands Trails: NY, OH, PA, WV

- New England Rail Trail Network: CT, MA, ME, NH, RI, VT

- Route of the Badger: WI

- The Miami LOOP: FL

Refine Data

The trail network will change and evolve over time as planned trail projects are constructed, alternative routes are considered to close network gaps, and development priorities change at the local and regional levels. Maintaining accurate trail network data and updating associated maps will be an iterative process. New datasets will be discovered, versions of existing trail data owned by trail network partners will be updated, new criteria and desired attributes will likely emerge, and GIS technologies will continue to advance. The entity responsible for collecting trail network data should also be prepared to take on the responsibility of updating and refining the data.

For example, the Capital Trails Coalition goes through an annual trail network data-update process. Each jurisdiction is asked to review the existing spatial data and attribution and provide edits and changes. This process allows the coalition to update the status of the trail network and closely track the percentage of trail completed while also providing opportunities to re-engage with each jurisdiction. Staying in close contact with the jurisdiction encourages consistency in data collection and management, and helps foster the relationships needed for the coalition to stay connected with jurisdictions through potential staffing and local administration changes. Additionally, as the coalition evolves and new people are involved, it will be important to refer to the criteria for trail network inclusion for clarity during data updating.

Project Prioritization and Gap Filling

A mapping process that produces accurate spatial data and attributes will allow the trail network coalition and its members to leverage that data for analyses to help advance the trail network vision. A collaborative and systematic mapping process will provide a solid foundation for performing analytics that guide project prioritization and gap filling and support equitable trail development planning practices. Additionally, accurate spatial trail network data can be a necessary foundation to understanding or estimating the cost of the network and developing an investment strategy.

RELATED: LEVERAGING DATA TO ADVANCE EQUITABLE PLANNING AND DEVELOPMENT

Project Prioritization and Impact Reporting

The Capital Trails Coalition in the Washington, D.C., metro area used an analytical process to prioritize new trail projects using threefold criteria. The criteria required that the trail network intersect the boundary of areas with high population density with low-income communities of color that are also designated Metropolitan Washington Council of Governments (MWCG) Activity Centers, where MWCG recommends that growth be concentrated. The coalition also asked each member jurisdiction to submit its own top trail-development priorities. The coalition then overlaid the two lists. This process yielded 40 featured trail projects, some of which are “Stated Jurisdictional Priorities,” “Planned Trail Analysis Priorities” or both.

RELATED: THE ECONOMIC, HEALTH AND ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFITS OF COMPLETING THE CAPITAL TRAILS NETWORK

Connectivity Analysis to Determine Low-Stress Bicycling Routes

Milwaukee’s exemplary trails, including the Oak Leaf Trail and Hank Aaron State Trail, serve as critical infrastructure for city residents, connecting communities and offering transportation and recreation benefits to those who use them. But the benefits that trails bring are not equitably shared among the people who live there.

An RTC BikeAbleTM study leveraged the trail data collected by the Route of the Badger coalition to understand access to trails and bicycle connectivity throughout the city. The study found that neighborhoods experiencing inequality in Milwaukee—those where a concentration of the population live under the poverty line, are unemployed, do not have a high school degree, do not own a vehicle, and are either African American or Latino—disproportionately lack access to biking and walking facilities.

Using BikeAble, RTC’s GIS-modeling platform that analyzes the bicycle connectivity of a community to determine the best low-stress route for bicycling between a set of user-specified origins and destinations, the study demonstrated that the completion of two key Milwaukee corridors that are part of the Route of the Badger network would increase trail access for more than 200,000 people in the city.

RELATED: RECONNECTING MILWAUKEE—A BIKEABLE STUDY OF OPPORTUNITY, EQUITY AND CONNECTIVITY

Integrating Concepts Across the TrailNation Playbook

Project Vision | Coalition Building | Mapping and Analytics | Gap-Filling Strategy | Investment Strategy | Engagement

Each element of the playbook to build trail networks is integrated. While the process is not linear, each aspect plays an important role. When mapping your trail network vision, consider the following points.

- Mapping and analytics bring the trail network vision to life. Mapping is the “what” and analytics is the “why.” The vision is fundamental to creating the criteria for trail network inclusion.

- The exercise of bringing many stakeholders together to map the trail network helps build and strengthen the coalition by encouraging collaboration across jurisdictions and across departments and agencies within jurisdictions. Make sure there are coalition members with the technical GIS expertise that can help with this process.

- By establishing and defining a trail network, and having an accurate and robust geospatial dataset, the coalition can develop a comprehensive gap-filling strategy. Data can be used to prioritize projects and bolster more in-depth planning and design work on gaps.

- Having a comprehensive trail dataset makes it possible to match gap projects with funding opportunities—aligning priority projects with the investment strategy and applying a geospatial lens on assessing available public funds.

- The trail network map, defined by robust and accurate geospatial data, is essential to any engagement strategy. By visualizing the scope and impact of the trail network, mapping is an important tool for building the political will and public enthusiasm needed to advance the vision.

Resources

Explore more resources to guide your thinking around building coalitions:

RTC’s Trail-Building Toolbox: Working With Metropolitan Planning Organizations

RTC’s Trail-Building Toolbox: Leveraging Data to Advance Equitable Planning and Development

Pennsylvania Environmental Council’s Inclusionary Trail Planning Toolkit