Coalition Building

Schuylkill River Trail | Photo by Laura Pedrick/AP Images

RTC’s TrailNation™ Playbook curates case studies, best practices and tools to accelerate trail network development nationwide. Explore each section for lessons learned that can support trail planners, municipalities, states and regions working to advance trail network projects.

Project Vision | Coalition Building | Mapping and Analytics | Gap-Filling Strategy | Investment Strategy | Engagement

Coalitions are critical to the success of trail networks. Designing an inclusive process to engage a broad network of partners can help to channel the energy, expertise and influence needed to grow support for and implement regional trail networks. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach to coalition building, this section of the TrailNation™ Playbook outlines some key factors to success and project sustainability, including the diversity of coalition partners, a strong and clear vision for the project, a governance structure and strategic plan that guide the work of the coalition, mutual benefits and shared participation among coalition members, and the ability to generate political, financial and community-based resources to implement the trail network agenda.

Why Coalitions Matter

“We all do better when we all do better.”

— Paul Wellstone

In a coalition, a group of people are united by a shared vision, harnessing the power of collaboration and diversity of thought, skill set and expertise to achieve significant goals. The success of a trail network demands this type of partnership, calling for a broad-based coalition of people and organizations from diverse sectors to generate the political will, technical expertise and sustained funding necessary to connect trails within and between communities—sometimes across county and state lines.

Why Coalitions?

Coalitions are an essential tool for generating the political, cultural and financial support necessary to advance trail networks from concept to reality, while also serving as critical engines of public engagement. Building trust and community support is fundamental to the success of any trail network, and a strong, effective coalition can play an important role in this effort.

Collective action, across ideologies, geographies and sectors, is a powerful component that propels advocacy movements and projects, such as trail networks, that can deliver transformative outcomes for people and places at regional scale. Often, this work can face difficult odds as communities prioritize trails alongside other public funding needs, deal with political differences that are critical to decision-making, and respond to local residents who may be afraid of change, have competing priorities or represent the “not in my backyard” mentality. Diverse coalitions are important to addressing many of these challenges and can deliver the most effective messengers and advocates to build support for the trail network.

High-functioning coalitions create a collaborative web of working relationships, breaking down boundaries between the public and private sectors, grassroots movements, local residents, nonprofit organizations and advocates, corporate interests and more. Coalitions build the framework for collective thinking and action, establishing clear and consistent channels for communication, collaboration, goal and vision setting, and work planning to achieve results. Coalitions can work to overcome challenges and adversity by pooling resources, developing shared advocacy and outreach strategies, and advancing trail networks—elevating the message that trail networks are not only essential to healthy communities, but are also entirely achievable in a pragmatic and fundable timeline.

Organizing a Coalition

When you begin building your coalition, the most fundamental question is whom it should include. A coalition that represents diverse stakeholder interests will deliver enhanced resources to your trail network implementation strategy while bringing credibility to the endeavor. What’s more, a coalition has the power to shape trail network development to foster social, institutional and economic stability by giving people an investment in local or regional outcomes.

As you consider the composition of the coalition, think about those who may be opposed to the trail network vision—and which messengers would be most effective in bringing them along. Think outside of the typical trail-building community: Trail networks bring direct benefit in myriad areas of focus, from housing to commercial real estate development, from small-business growth to regional economic incubators, from quality of life to climate protection and active transportation. Consider the power dynamics in the coalition, and ensure balance between those who represent the neighborhood and community that will be served by the trail network project and those who may be perceived as outsiders. Consider the balance of grassroots and grasstops participation. By expanding beyond the “trail-friendly” audience of planners, advocates, and bicycle and pedestrian groups, you can build a powerful coalition that will carry a range of perspectives, expertise and influence.

Consider expanding the tent to include:

- Economic development professionals

- Chambers of commerce

- Business improvement districts

- Public health agencies

- Community development corporations

- Land use planning and community design professionals

- Social equity community organizations

- Local and regional anchor institutions (e.g., major corporations, universities, hospitals, etc.)

- Major employers

- Real estate developers

- Environmental and watershed advocacy organizations

- Public agencies (e.g., parks, public works, transportation, water and sewer districts, transit, housing, etc.)

- Elected officials and appointees representing local, municipal, state and national government

As your coalition evolves over time, so will the needs of the project. Coalition members who were essential to delivering project credibility may not be as critical to the work once the project gets rolling. A healthy coalition should be designed to ebb and flow, evolving over time to best serve project needs. Planning for this evolution is important. Factors to consider may include:

- How much overlap exists between each member’s interests and the overall trail network strategy

- The quantity and types of resources a partner can mobilize and how resources can be shared among partners

- Key issues that require resolutions as the trail network is built and whether coalition stakeholders can be effective in the process

- A partner’s ability to broaden the reach of the coalition among key audiences

- A partner’s ability to leverage philanthropic, public and other sources of funding to advance coalition goals

Coalition checklist—do you have your bases covered?

As you map out the stakeholders you’d like to include in your coalition, consider if you have participation from people who can contribute to all the elements of the TrailNation Playbook. Consider who can manage a strategy and workplan associated with:

Consider this example from the Capital Trails Coalition, a TrailNation project that illustrates varying levels of engagement and participation needed for the coalition to thrive.

What Brings the Coalition Together?

Many factors help shape a coalition and bring coalition partners together around a shared project vision. These factors may include common goals, overlapping missions, overlapping project implementation interests or workplans, transactional relationships, or general agreement that collaboration can be powerful in achieving transformative impact for people and places.

While a coalition is likely to come together around a shared project vision, the work will be defined by a strategic planning process that will set measurable project objectives, establishing roles and responsibilities for coalition partners. The strategic plan will identify the strengths and weaknesses of the coalition to be addressed as the coalition works to build out the trail network.

As with any activity, participating in a coalition can bring benefit to the participants as well as risk. As you shape your invitations, consider some of the questions potential coalition partners may be asking themselves, such as how they can best serve the group, what will be expected of them and whether they have anything at stake in participating. Defining the value proposition for potential coalition participants will be a helpful recruiting tool.

Themes of Effective Coalition Building

- Understand the value proposition of the coalition.

- Agree on a shared project vision.

- Develop measurable project objectives and goals.

- Ensure the representation of diverse stakeholder groups.

- Define clear roles and responsibilities.

- Plan to leverage coalition relationships.

- Anticipate and be transparent about leveraging coalition members’ resources.

Power Mapping Your Way to a Superstar Coalition

Relationship dynamics are the building blocks of successful coalitions. As we seek to bring influence on issues that will fundamentally shape community design, our personal, professional and political network of relationships—and the relationships each coalition member brings to the table—can be invaluable. Power mapping is a visual tool used by advocates to understand these relationships and identify the most impactful relationship-driven strategy to promote change—such as a new paradigm for trail networks.

Ideally, power mapping can be used to target coalition growth in ways that foster diversity of participation, identifying influencers who can advance the project effectively and efficiently and in ways that are representative of and appropriate for the local community. Power mapping will also identify how best to align coalition members’ interests, technical skills and relationships in support of project goals.

RELATED: NATIONAL EDUCATION ASSOCIATION POWER MAPPING 101

Power mapping can help a coalition identify where relationships and collaborations are strongest, and where there is room for growth. A power-mapping exercise may help your coalition decide where outreach is needed to establish stronger relationships in a particular sector, geography or community. For example, through power mapping, you may discover the coalition is not connected to the anchor institutions that are critical to a particular corridor gap, yet a member of the coalition has a direct relationship with a decision-maker at one institution that could be leveraged for a meeting. The exercise may also help the coalition identify general strengths that can be leveraged to develop new relationships or land easy wins that parlay into momentum for the trail network. For example, your coalition may include a number of supportive neighborhood groups along one particular corridor. By focusing your energy with these partners and along this corridor, you can make early progress for trail network development, demonstrate community enthusiasm for the project and build momentum that can carry the project vision to the rest of the region.

Begin your power-mapping journey with the following questions. Consider using a visual tool such as a whiteboard or Google’s digital Jamboard to illustrate the discussion. Invite a facilitator or a key convener from within the coalition to lead this exercise.

- What are the strengths of the current coalition makeup?

- What are the weaknesses of the coalition?

- Where are there areas for growth?

- Who needs to do something differently for the coalition to be successful? Who can engage them?

- What sectors or industries are missing in the coalition?

- Who or what group, specifically, is missing?

- Who is best suited to reach out as an ambassador of the coalition to invite the missing links to become part of the process of building a vibrant coalition?

Sustaining a Coalition

Over time, coalitions will have to adapt. As project needs evolve, the challenge is building a coalition that is resilient and able to respond to changes on the ground. A thriving coalition course-corrects and recalibrates in response to internal and external changes. While change is inevitable, you can prepare. As your coalition grows, anticipate how you will manage the following:

- Political changes and changes in elected leaders

- Budget changes that affect trail funding, either reducing or increasing resources available

- Changes in staff and leadership among coalition organizations

- Progress being made along the trail network—trail miles being built or not being built quickly enough

- Disagreements among coalition partners

- Cycling through the phases of trail network development, from making the case and building the vision to implementation, trail building, trail management, and trail promotion and programming

As projects evolve, so do coalitions. The focus and composition of a successful coalition on day one of a trail network project is likely to look much different than a successful coalition several years into the effort. For example, a coalition may be focused first on advocacy, building the vision and formalizing buy-in for the trail network. Once that buy-in is established, the coalition’s work may shift to communications strategy, fundraising, trail building, trail use, advocacy, or programming and maintenance—complementary but distinct technical skills required in the first phase. It is common for coalitions to shift from a grassroots or nongovernmental beginning to more formal public or quasi-governmental groups as work needs shift from visioning to implementation, or as the trail network shifts from concept to funded, shovel-ready projects. In this scenario, early grassroots supporters and visionaries can stay involved by the formation of a working group within the coalition focused on programming, engagement or trail management.

While the coalition’s journey is unlikely to be linear, you can prepare for changes that may happen concurrently or in fits and starts. These transitions can occur in multiple ways. Examples of practices that coalitions have employed to encourage evolution and endurance include:

- Evolving the coalition into a standalone organization to ensure the necessary resources and staff to advance project goals

- Establishing agreements between partners to formally provide staff to support and manage the coalition

- Having a municipal planning organization or council of governments adopt the trail network as an official regional priority, allowing that entity to act on behalf of the coalition through local governments

- Forming a working group of the coalition made up of public agency partners to liaise between the coalition and the trail-building municipality

Keep in mind that no matter how you design the coalition or establish the strategic plan, building trail networks takes time. Keeping stakeholders and coalition members involved over the long haul requires coalition maintenance. Anticipate the need to focus on the health of the coalition so that members remain motivated and engaged, even as the project transitions from the visioning stages to implementation.

Coalition Philosophies

The organization and structure of a coalition can take many forms, depending on the needs of the project and the resources available to support the coalition’s work among other considerations. Here is a selection of coalition philosophies that can be effective in the work to build trail networks.

Consultant Led

Many coalitions formed to advance trail networks are considered “consultant led.” This typically means that a group of coalition partners engages with a professional facilitator or consultant to lead the strategic planning, vision setting, power mapping and structure of an emerging coalition. This can also lead to the consultant’s becoming the organizing convener or facilitator of ongoing coalition meetings, planning sessions or working groups.

It takes a highly specialized skill set to work in this capacity. Consultants who are successful in leading this type of work have a background in facilitating groups of people, management theory and practice, coaching, nonprofit leadership, and government and policy experience. In addition, they often possess proven technical capabilities in regional planning, geography, environmental conservation, community development, economics and relationship building.

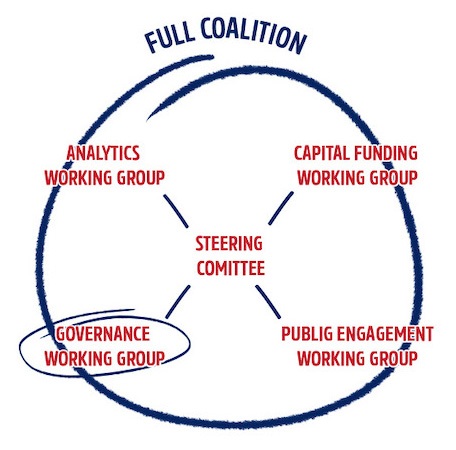

Governance on the Circuit Trails

The Circuit Trails coalition is working toward a vision of an 800-mile trail network that connects across the nine-county region in Greater Philadelphia and South Jersey. The coalition has a clearly established governance framework and strategic plan to guide member participation.

Collective Impact

“Collective impact” describes an intentional way of working together and sharing information for the purpose of solving a complex problem. Participants are likely to include individuals, organizations, grant makers, and even representatives from the business community and government. Proponents of collective impact believe the approach is more effective than if a single organization tackles the issue independently. Research illustrates that key characteristics are present in a successful collective impact initiative. An additional condition—inclusion of the community’s voice—is particularly important to collective impact initiatives focused on the process of trail network development:

- Participants share a vision of change and a commitment to solve a problem by coordinating their work; they agree on shared goals.

- Participants agree to measure or monitor many of the same things, so that they can learn across the initiative and hold each other accountable.

- A single organization, a single person or a representative steering committee serves as the backbone of the coalition. The backbone is often most responsible for “building public will” and making sure the initiative stays focused and moves forward. The backbone also focuses on building a culture that encourages information sharing and candor, and typically plays an administrative role such as convening meetings, coordinating data collection, connecting participants with each other and facilitating the activities of the initiative.

- Activities of the initiative are described as “mutually reinforcing” because they are designed to remind all participants that they depend on each other to move the initiative forward. Mutually reinforcing activities ensure that the interests of the participants are aligned, are directed toward shared measurement and are making progress toward common goals.

- Resources are available to sustain the coalition, and consistent and open communication between all the participants is expected, so that everyone is informed and stays motivated over time.

Source: https://ssir.org/articles/entry/collective_impact

The Intertwine Alliance is working to preserve and nurture a healthy regional system of parks, trails and natural areas in the Portland, Oregon–Vancouver, Washington, region, applying a collective impact model to address a wide range of issues related to nature in the metropolitan region.

RELATED: VOICES FROM THE FIELD: 10 PLACES WHERE COLLECTIVE IMPACT GETS IT WRONG

Systems Change Approach

According to London Funders, systems change is defined as “addressing the root causes of social problems, which are often intractable and embedded in networks of cause and effect. It is an intentional process designed to fundamentally alter the components and structures that cause the system to behave in a certain way.”

The systems change approach to coalition building for trail networks emphasizes the role of coalition partners in promoting connected walking and biking infrastructure as part of a solution to systemic challenges in a community or beyond. The coalition may form around critical social issues such as enhancing quality of life, reducing pollution levels, increasing participation in civil discourse or improving education, for example, but positions the trail network as an important component in meeting these goals. This approach begins by working collaboratively with partners to identify the challenges in a community, investigate the root causes of those challenges and explore the opportunities for trails to provide solutions. Focusing on the evidence that shows how changes to the built environment through a trail network will offer solutions and create improved outcome for community members and trail users is essential in this process.

RELATED: UNDERSTANDING POLICY, SYSTEMS AND ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE

Other Examples of Effective Coalition Approaches

Approaches to building, managing and maintaining an effective and successful coalition are varied and can be evolving. Here are some other examples of effective coalition models.

The Chesapeake Bay Collaborative is a municipal-led coalition, focused on building collaboration among federal, state and local public agencies.

The Caracara Trails, a TrailNation Project in the Lower Rio Grande Valley of Texas, offers a strong example of a municipal-led, county-level coalition, organized in partnership with leadership and participation of the region’s many small municipalities alongside other regional special interests. The coalition emerged as part of a comprehensive regional planning process.

Houston’s Buffalo Bayou Partnership is an example of an organization-led coalition focused on the development of a 10-square-mile stretch of the bayou that flows from Shepherd Drive, through the heart of downtown into the East End, and on to the Port of Houston Turning Basin.

Other examples of coalitions working to advance trail networks:

Integrating Concepts Across the TrailNation Playbook

Project Vision | Coalition Building | Mapping and Analytics | Gap-Filling Strategy | Investment Strategy | Engagement

Each element of the playbook to build trail networks is integrated. While the process is not linear, each aspect plays an important role. When establishing a coalition for your trail network vision, consider these points.

- A clear vision guides the coalition’s goals, practices and outcomes.

- Engaging geospatial data specialists as coalition members will provide the technical mapping and analytics expertise to create powerful data-centered tools to prioritize corridor gaps, measure mileage progress, and tell unique stories based on the demographics and topography of your trail network.

- A coalition can provide local knowledge of the cultural, political and geographic landscapes that will inform how gap filling in the trail network is prioritized to meet community needs and align with practical realities.

- A diverse coalition with a wide reach, strong relationships and funding expertise is well positioned to access all available investment strategies and resources to fund a trail network.

- A coalition comprising partners with deep community relationships and an excellent track record in outreach can foster engagement, building public support and enthusiasm for a trail network among diverse constituencies.

Resources

Explore more resources to guide your thinking around building coalitions:

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation: Investing in Systems Changes to Transform Lives