Revisiting John Brown’s Raid on Harpers Ferry

History Along the Great American Rail-Trail: A Trip to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia, Reveals Forgotten Details Behind One of American History’s Most Daring Uprisings

In the late hours of Sunday, Oct. 16, 1859, a band of 22 armed men slipped out of a darkened Maryland farmhouse and began a silent procession to Harpers Ferry, Virginia, a bustling town perched at the confluence of the Shenandoah and Potomac rivers about 5 miles away. Among them was abolitionist John Brown and his two sons, as well as a fugitive slave from South Carolina, an African American student from Ohio, two quaker brothers from Iowa, and a motley group of radicalized men who had come from Connecticut, New York, Pennsylvania and elsewhere.

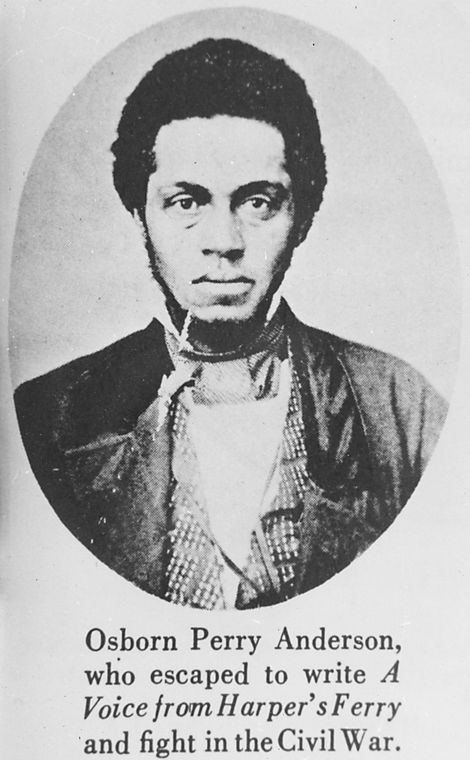

Without a word, they “marched along as solemnly as a funeral procession” until they reached their destination, the U.S. Armory, Arsenal and Rifle Factory, according to one of the men who joined Brown, Osborne Perry Anderson. A free Black man from Pennsylvania, Anderson would be one of only five men to survive the 36-hour rebellion and its aftermath, a bloody episode that would divide the already fracturing nation—and hasten the coming of the Civil War.

Today, visitors on the C&O Canal Towpath can travel the same path as Brown and his men, from the Kennedy Farm in Washington County, Maryland, to the former federal armory where those 22 men made their stand, hoping their doomed mission might incite a massive slave rebellion and change the course of American history.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2025 issue of Rails to Trails magazine and has been reposted here in an edited format. Subscribe to read more articles about remarkable trails while also supporting our work.

Who Was John Brown?

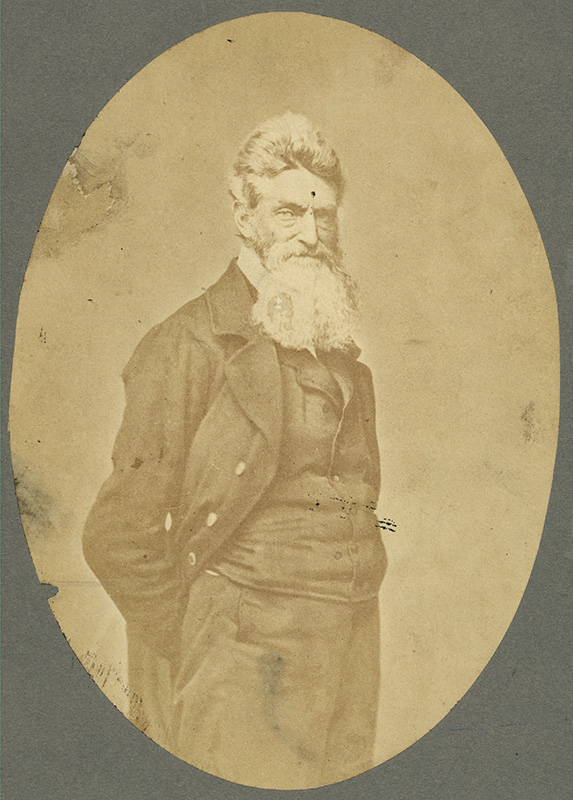

“Others saw him as a freedom fighter, as someone who was willing to sacrifice his life for the cause.”

— Hilary Green, historian and professor, Davidson College

Born in 1800 in Torrington, Connecticut, John Brown was raised by Calvinist parents who abhorred slavery. When the family moved to Ohio, Brown’s father Owen operated a safe house for fugitives traveling north on the Underground Railroad. By the time Brown was an adult, he believed himself an instrument of God, his divine mission to end slavery in the United States. At the funeral of abolitionist publisher Elijah Lovejoy in 1837, Brown stood before the mourners and declared, “I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery.”

But it would take a decade and a half for Brown to go from an ardent, if average, abolitionist into a man willing to kill and die for the cause.

In 1854, when Congress passed the Kansas-Nebraska Act, creating the new territories and allowing the white men in them to vote whether each would allow slavery or not, advocates from both sides began pouring into Kansas, hoping to influence the vote. A year later, amid the tumult and violence that would come to define the “Bleeding Kansas” era, Brown and his five sons arrived in the territory, ready to take up arms with the free-soil forces. In the spring of 1856, Brown and his sons killed five proslavery advocates at Pottawatomie Creek, a brutal attack that became known as the Pottawatomie Massacre and transformed Brown into a fugitive—and deeply divisive figure.

“For some, he was betraying his race in fighting for and alongside African Americans,” explained Hilary Green, a historian and professor at Davidson College in North Carolina. “Others saw him as a freedom fighter, as someone who was willing to sacrifice his life for the cause.”

More certain than ever that ending slavery would require a bold and violent act, Brown began making plans for his raid on Harpers Ferry. There, he would capture the federal arsenal, distribute arms to the enslaved people he believed would flock to his effort, and set off for the South to carry out a slave rebellion the likes of which this country had never seen.

An Infamous Raid—and Five Forgotten Black Men

In the summer of 1859, Brown arrived in Harpers Ferry and rented the Kennedy farmhouse, a two-story log cabin with a gabled roof about 5 miles away. Concealed behind a new, long beard and going by the alias Isaac Smith, Brown told neighbors he was prospecting for minerals.

In actuality, the farmhouse was teeming with battle maps and weapons and raiders. “He had about 200 Sharps rifles and 1,000 pikes,” said Mike Vidmar, a certified guide with the Harpers Ferry Park Association, “and 21 men who basically hid in the attic.”

Two of Brown’s daughters (one by marriage) also stayed at the Kennedy Farm. “They cooked for the men, but they also were the gatekeepers. When nosy neighbors got too close, the girls would stop them at the door,” said Vidmar.

Of the 21 men Brown had recruited, five were Black. Lewis Sheridan Leary and John Anthony Copeland Jr. were from Oberlin, Ohio. Shields Green had escaped slavery in Charleston, South Carolina, and went by the nickname “Emperor,” thanks to rumors about his descent from African royalty. Dangerfield Newby was a formerly enslaved man, also from Ohio, who had joined Brown’s men hoping to win his enslaved wife’s freedom.

Anderson—who was born to free Black parents in Pennsylvania (his grandfather was a white slaveowner)—had met Brown during one of the abolitionist’s meetings in Chatham, Ontario.

As summer turned to fall, Brown hoped more fighters would arrive in Maryland.

“But by October, he realized he was not getting any more men to join him, and he was afraid he was going to be found out,” Vidmar said. Despite the small group in his charge, the park guide believes that Brown marched to Harpers Ferry with a sense of optimism. “I think he figured it was doable.”

But Brown had vastly underestimated how many white men would arrive to put down what they saw as an insurrection.

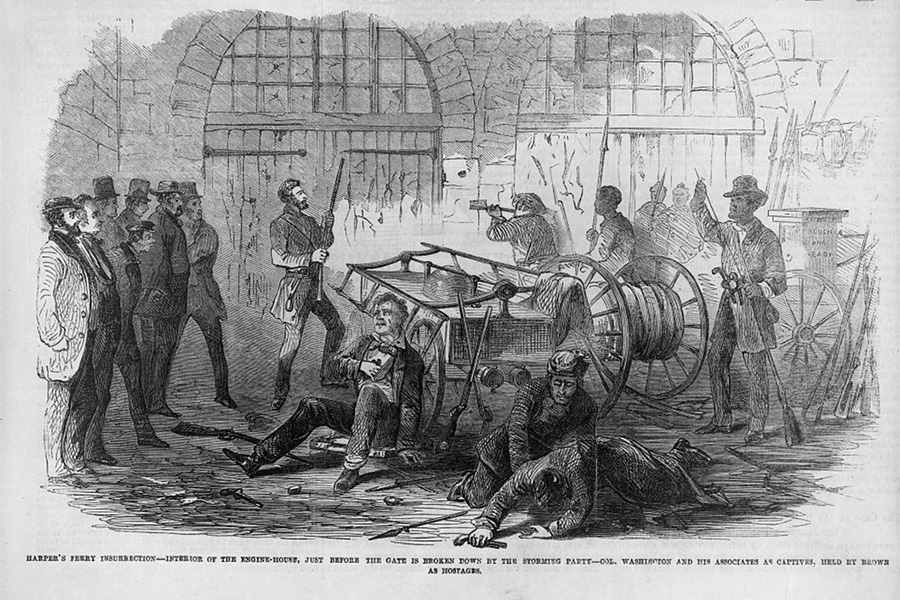

“The federal armory had 400 workers; the town had a population of about 3,000. The militia from nearby Frederick and Baltimore were able to use the railroad to get there quickly,” explained Vidmar. “By the afternoon of the 17th, he was surrounded.”

When the sun rose on the morning of the 18th, a company of 90 U.S. Marines, led by Lt. Col. Robert E. Lee, future Confederate general and a slaveowner himself, were ready to take on John Brown’s tired and desperate men, who had barricaded themselves in the armory’s 35.5-foot-long, 24-foot-wide fire engine and guard house.

“They bust in,” said Vidmar, “and the episode is over in less than a minute.”

The Legacy of Harpers Ferry

Brown’s trial lasted five days, and it took the jury 45 minutes to reach a verdict: John Brown would be hanged on Dec. 2, 1859. On the way to his execution, he handed a note to one of the guards, reading, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood.”

His words were prophetic—the first shots of the American Civil War were fired just 16 months later.

According to Green, Brown’s “memory was immediately being used” by both sides of the conflict. “In the North, he was seen as a martyr almost from the beginning, while Southern states pointed to John Brown and said, ‘this is why we’re leaving.’”

For African Americans, Brown became something of a folk hero, said Green. “The song ‘John Brown’s Body’ was chosen by African American regiments in particular as their regiment song; they sang it in their camps, at the reunions of Black soldiers and in churches on Memorial Day.”

The five Black men in John Brown’s army, all of whom—except Anderson—were killed during the raid or in its aftermath, have largely been forgotten, said Green, despite Anderson’s 1861 penning of—with the assistance of Mary Ann Shadd Cary—the only firsthand account of the event in his pamphlet, “A Voice from Harper’s Ferry.” Anderson went on to enlist in the Union Army and died in 1872 at the age of 42 in Washington, D.C.

“The only people who tended to know these men were writers like W.E.B. Du Bois and Frederick Douglass, and African American history buffs,” added Green.

In 2009, the National Park Service invited descendants of the Black men to attend the sesquicentennial commemoration of the raid. “Still, most people don’t know their names,” said Green. “John Brown became this mythic figure that persists in books, movies, songs. We don’t think about Harpers Ferry without thinking of John Brown; now we just need to think about the other five men.”

From Raiders to Crooners: The Long Life of the Kennedy Farm

In the 1950s, local members of the Improved Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks, known as Colored Elks, or Black Elks, bought the remote Maryland farm where John Brown and his men staged their ill-fated raid on Harpers Ferry. While the Black Elks had envisioned a sprawling development that would include a retirement center, youth center and 200 cabins, the disrepair of area roads (and the refusal by county officials to fix them) would ultimately dash their plans. Instead, the Black Elks began renting out the space for concerts. Soon, the Kennedy Farm was a popular stop on the Chitlin’ Circuit, a collection of venues that hosted Black performers. It didn’t take long for top talent to arrive.

“Out in the middle of nowhere, you could go see Little Richard, Aretha Franklin, B.B. King, James Brown,” said Mike Vidmar, a certified guide with the Harpers Ferry Park Association. “It was a who’s who of Black musicians.”

Revisiting History on the Great American Rail-Trail

Today, Harpers Ferry (which is located in what is now West Virginia) is a confluence of rivers and trails; both the Appalachian Trail and the C&O Canal Towpath, a host trail of the cross-country Great American Rail-Trail®, cut right through the heart of Harpers Ferry National Historic Park, where visitors can learn about John Brown’s life and famous raid—as well as the men who joined him.

The Kennedy Farm, where Brown and his men languished for a long, hot summer planning their attack, is also accessible from the C&O, just 5 miles north of town. The interior is closed for renovations, but visitors can still tour the property, which looks much like it did in 1859. No matter where or when you visit, Mike Vidmar encourages arriving with an open mind.

“A lot of people come to Harpers Ferry with a predetermined view of John Brown. Many think that he was a murderer, or a crazy man,” he said. “But remember, your perception of him is based on your background.”

No matter how we choose to see John Brown today, there’s no question that the 22 men who marched into Harpers Ferry on that dark Sunday night in 1859 changed America forever.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.