American Icon: The Great American Rail-Trail Is on Its Way to Fulfilling a Cross-Country Vision

Five Years After Launch, the Great American Rail-Trail Is on Its Way to Fulfilling a Cross-Country Vision

Whitney Washington knew she’d embark on a cross-country bike trip of some kind, eventually. When a friend sent her an article about a burgeoning route called the Great American Rail-Trail®, it gave her something concrete enough to start her journey, she said. Here was a map of a 3,700-mile path that charted a course for her. She could see what trails were and weren’t complete. And importantly, she could see that the starting point, the C&O Canal Towpath, the first long-distance trail along the route leaving Washington, D.C., offered a protected, bike-friendly start to the endeavor. It served as a 180-mile runway to help launch her trip in the summer of 2021.

“When I learned about the Great American, and watched and rewatched other riders’ experiences, I knew I wanted to try too,” she said. “It felt right. Now that I’ve experienced that dream, it lets me know no dream is unachievable. Riding the Great American at that time was a wild idea. It isn’t completed, I was a novice, and there was so much I had to learn while I was out there. Nevertheless, as long as I kept going, that wild idea became my reality.”

Officially launched in 2019 by Rails to Trails Conservancy and hundreds of partners, the Great American Rail-Trail project turns 5 this year. The concept of a route between Washington, D.C., and Washington State has already helped inspire trail advocates across its 12 states and the nation’s capital to fill in existing gaps. Being part of the project’s overall cross-country vision has kicked many existing development efforts into high gear, said Kevin Belle, RTC’s project manager for the Great American Rail-Trail.

“It has definitely allowed people to think bigger than perhaps they have in the past,” Belle said. “And to make it feel like [certain goals are] more realistic. A lot of people have thought about filling this gap or that gap. But now they can say: ‘We’re part of this bigger vision. There’s momentum.”

Launched in 2019, the Great American Rail-Trail® will eventually connect Washington, D.C., and Washington State across 12 states and the nation’s capital. Featuring treasured historical sites, landscapes and urban centers—the 3,700-mile trail will serve millions of people while generating hundreds of millions of dollars for adjacent communities. Here, on the Great American’s five-year anniversary, we explore its impact and its future.

Catalyst for Development

Though it was announced in 2019, the Great American Rail-Trail has long been a concept, with history dating back to the 1990s (read about it in Rails to Trails‘ 2019 cover story). Marianne Fowler, RTC’s senior strategist for policy advocacy, said the Great American has been “something that we had our eye on and were looking at opportunities [for it] along the way, to make sure we didn’t let a major one slip by.” Fowler, who coined the name of the cross-country trail, has visited densely urban areas and rural expanses from coast to coast to help see the route’s development through.

Right now, the Great American Rail-Trail is 55% complete. That translates to 2,059 miles of protected trails, with another 160 or so miles in development as this sentence is being typed. Ten of the 12 states on the route are over halfway there. Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Idaho are each down to one remaining trail gap. Maryland’s all done, while trail developers in Indiana, working with “pennies from heaven,” as one described the state’s Next Level Trails funding, are using the Great American as motivation to be the next state to close its gaps.

In talking with trail developers across the Great American Rail-Trail, Belle said he’s seeing that being part of it is personal for the people who’ve been pushing to build walking and biking paths for years. They realize the benefits of a trail that connects to the next town, and creating a tourism strategy, while also giving their kids a safe way to get to school, he affirmed.

Others, like Amanda Cooley, planning director for Powell County, Montana, got swept up by the cross-country vision. When Cooley moved to Deer Lodge about two years ago to start a new career in planning, she inherited a trail project that was nearing its completion. The Old Yellowstone Trail was expanding by about 4 miles. The trail now runs about 10 miles and links the Grant-Kohrs Ranch National Historic Site in Deer Lodge up to the community of Garrison by way of a path that crosses a set of bridges over the Clark Fork River, offering stunning views of the Flint Creek Range in an area dense with western Montana wildlife.

“I stepped into this trail project and was very fortunate that there was already a lot of momentum, so I just got to help kind of oversee the trail construction and completion,” she said. “And still though, I had no idea what the context was of that development. I was just like, ‘Cool, we’re building a trail.’”

But soon after she started her job, Belle reached out. Cooley said he introduced her to the idea “that this small project that we were working on was part of something so much larger.”

Through regional connections Cooley made during virtual meetups organized by RTC, the scope of her work dramatically broadened, and relationships she was building in a region new to her multiplied. It began with a connection with Jackson Lee, project specialist with Missoula County Parks, Trails and Open Lands, about 60 miles east of Deer Lodge. RTC’s event, Cooley said, gave her the space to talk about her community’s project and prompt a question. “And that question was, ‘What would it look like if we connected our two communities?’”

That question is now being asked across the region, Cooley said, thanks to the Great American Rail-Trail.

Along with partners in Missoula County and the City and County of Butte-Silver Bow, the Mineral County Rails to Trails and Granite County Flint Creek Trails associations, the Missoula Metropolitan Planning Organization and others, Cooley is part of a group effort to build out a 262-mile trail system they are calling Parks to Passes. To get there, they’ve worked together on a U.S. Department of Transportation RAISE grant application that highlights the transformational safety, environmental, economic, and mental and physical health benefits such a network will bring.

She said a convergence of three factors—the collection of regional leaders who’ve bought in, RTC’s guidance, and the federal funding opportunity—have formed a trifecta that could transform the region.

Momentum Generating Across Much of the Route

Efforts surrounding many of the remaining projects along the Great American predate its 2019 announcement, often by decades, but many are building or rebuilding momentum because of it. Randy Kline, statewide trail coordinator with Washington State Parks, said the Great American Rail-Trail project helps their developers keep focused on the state’s 287-mile Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail. This is because of the trail’s outsized role in the project—as a host taking people across most of Washington. “Being part of something larger is compelling for many trail users,” he said.

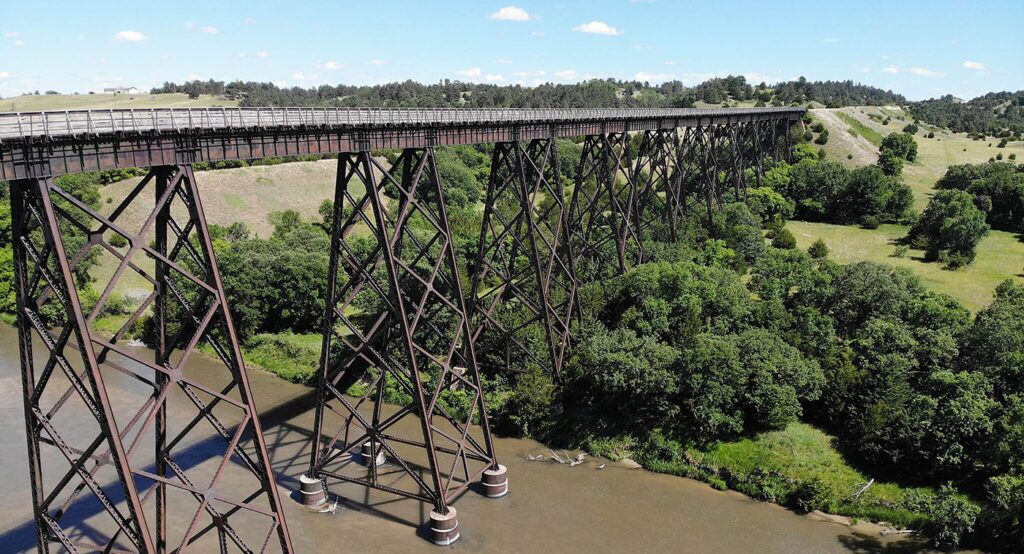

Along the trail, the much-heralded 2022 opening of the Beverly Bridge provided a major missing connection across the Columbia River. Cyclists had to pedal nearly half that distance—125 miles—out of the way to cross the Columbia on the nearest pedestrian bridge, or they had to bring a support vehicle, or make friends at a nearby grocery store in the hopes that someone would ferry them across on nearby I-90.

The Beverly Bridge became a state priority; it received over $5.5 million in funding appropriations in Washington’s 2019–2021 capital budget. Completing this major project, coupled with its ties to the Great American Rail-Trail, has built momentum for further trail development, Kline said, including the completion of the Tekoa Trestle, new surface improvements and the replacement of the Crab Creek trestle east of Beverly.

Next Level

In Indiana, trail development has received moonshot-level state funding backed by bipartisan support that starts with a mandate from Gov. Eric Holcomb via the $180 million Next Level Trails program. In Holcomb’s interview when he was named 2021 Rail-Trail Champion, he said he liked the state’s odds of closing its gaps before others on the route do. Mitch Barloga, active transportation manager with the Northwestern Indiana Regional Planning Commission, said the cross-country concept put a charge into funding and planning many of the remaining gaps. A 2.3-mile extension of the Pennsy Greenway in Schererville is among the most recent Next Level-funded projects to open along the Great American.

And recently, Holcomb announced that $2.9 million of Next Level Trail funds would finish the final portion of the trail in Crown Point, connecting Lake County with the southern Chicago suburbs in neighboring Cook County, Illinois. Barloga said the Great American Rail-Trail announcement helped revive that effort after an initial proposed route proved unworkable.

As more trails come online in Indiana, Barloga said he’s seen demand for the “community elixirs,” as he called them, increase.

“I mean, there’s just so much that a trail brings to our community, and they’re so embraced and loved and used,” he said. “And, again, when you have a larger system, such as a Great American in place, it also will bring a healthy amount of tourism and attraction to the state as well. And these communities, these very small towns along the particular route, are going to just see a boom in visitation and everything that goes along with that.”

Economic Driver

For the next few paragraphs, imagine the Great American at the finish line—100% completed, its 88 remaining gaps filled. How would that open up outdoor tourism and bike travel across the country? How would it serve the residents of the communities where those trails run?

RTC commissioned Headwaters Economics not to imagine it so much as to estimate it in a 2022 economic impact report. “The cross-country route will serve as a catalyst for economic growth,” the economists wrote. “Hundreds of communities along the route will experience new opportunities for business development and tourism thanks to the Great American Rail-Trail, all while contributing to the growth of the country’s burgeoning outdoor economy—one of the fastest-growing sectors in the United States.”

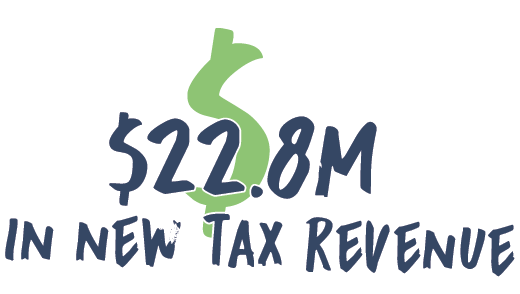

Based on a model that factored in existing trail data, daily spending estimates across multiple U.S. regions and many more factors, they estimate that a year on a completed Great American will produce more than 25.6 million trips, 2,500 new jobs, more than $229.4 million in visitor spending, $104 million in labor income, $22.8 million in new tax revenue and $161 million contributed to the GDP.

Trail advocates across the route have visions for how portions of these figures could manifest in their communities. In western Montana, Cooley said bike tourism could slow visitors down in an area that’s often on the way to a destination. “We’re halfway between Yellowstone and Glacier (national parks),” she said. “We also have a national park in town. So we’re ideally situated geographically to be able to attract people.”

“The small towns along the Cowboy Trail … stand to benefit greatly from getting more people arriving on two wheels.”

Julie Harris, Founding Executive Director, Bike Walk Nebraska

In Malden, Washington, the community’s new trailhead is the first one on the rugged, but developing, eastern half of the Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail. The eastern Washington community was nearly completely decimated by the Babb Road Fire in September of 2020. The opening of the trailhead has been tied to Malden’s rebuild. Kline said residents embraced the project, advocating for amenities like water stations for people, dogs and horses, a picnic shelter and a bike repair station. “In my conversations with the town of Malden, bike tourism is certainly something they are looking forward to,” he said.

In northern Nebraska, home to the Cowboy Recreation and Nature Trail, another of the Great American route’s longest stretches, envision a rural Nebraska version of the Katy Trail in neighboring Missouri.

“The small towns along the Cowboy Trail, which roughly parallels U.S. Highway 20, stand to benefit greatly from getting more people arriving on two wheels,” Julie Harris of Bike Walk Nebraska said in a 2022 press release announcing that four Nebraska cycling advocacy groups were forming a Cowboy Trail Coalition to push for maintenance and completion of unimproved trail portions.

George Ledbetter, treasurer of the Chadron-based Nebraska Northwest Trails Association (NNTA), said the group is focused on a key 5-mile link in the Great American route that will bridge a gap between Chadron and the current western terminus of the Cowboy Trail. An environmental study is underway for the connector’s first mile, and its development is igniting a chain reaction of conversations and actions in the surrounding areas.

While images from the eastern half of the Cowboy Trail grace Nebraska tourism magazine covers and websites, its western counterpart remains comparatively undeveloped. Nebraska Game and Parks, which owns the vast Cowboy Trail, contributed grant money to the Cowboy Trail Connection project, which got off the ground thanks to a $178,000 federal Recreational Trails Program Grant, a 20% matching one from Dawes County’s tourism board and an RTC grant.

Ledbetter said the group’s commitment to connect Chadron out to the Cowboy Trail, coupled with the longtime efforts of Cowboy Trail West, another coalition member, has spurred activity across the westernmost 25 miles of the trail. Once those miles are built out, they will connect to the only surfaced section of the Cowboy Trail west of Norfolk, a 16-mile stretch from Gordon to Rushville that Cowboy Trail West members led a grassroots charge to develop. “We’re really excited about the idea of being able to ride all the way from Chadron to Gordon, which is about 50 miles, [on trail],” Ledbetter said.

Brittany Helmbrecht, NNTA president, said the Great American Rail-Trail helped ramp up those conversations and build the coalition that the NNTA joined. “It’s also helped us connect with our counterparts to the west, in Crawford,” she said. “And it has started that conversation of, ‘How do we get to Casper, Wyoming?’ I’ve met with the Casper folks, and we’ve talked just in passing about, ‘Isn’t it going to be great when we can meet in the middle, because our towns are now connected by this trail?’”

Northern Cheyenne Healing Trail

Each path along the Great American Rail-Trail® has a story, no matter its size. In northwestern Nebraska, the developing 4-mile Northern Cheyenne Healing Trail will offer a space to remember and honor 130 tribal ancestors forced to fight for their freedom after being held captive at nearby Fort Robinson in the winter of 1879.

The trail will offer four points along its path for people to pause and reflect on the Cheyenne’s principles: respect, knowledge, wisdom and spirituality. The trail will also include historical markers about those who—faced with captivity and demands by the U.S. government to return to a barren territory in Oklahoma—chose to break out of Fort Robinson and attempt to return to their northern homeland, despite freezing temperatures and pursuing forces.

“They opted to break out, and most certainly die, but to die in their homeland where their ancestors were buried,” Northern Cheyenne author and historian Gerry Robinson told RTC in 2022. “Because of the determination—the incredible sacrifice of our ancestors—we have a place we can call home today.”

Learn more about the Journey Home Trail on the TrailBlog.

Future Potential

“It’s not enough to build a trail; you have to plan for its future.”

Marianne Wesley Fowler, Senior Strategist for Policy Advocacy, Rails to Trails Conservancy

Fowler was asked to envision the Great American five years from now. What will be completed that isn’t yet? Fowler, who thinks in terms of projects, had a list. The completion of a bridge across the Ohio River that includes bike-bed facilities for those crossing from West Virginia to Ohio or vice versa. Connecting the Illinois and Michigan Canal State Trail and the Hennepin Canal Parkway. Filling the gap in western Idaho to link that state with Washington. And connecting Seattle to the Pacific Ocean via the Olympic Discovery Trail.

Fowler was with Belle in Worland, Wyoming, the day we chatted. The night prior, they’d talked trail development in front of what Fowler said was an attentive, supportive city council. One attendee even took Belle up on an invite to talk further at Stogie Joe’s, a nearby pizza place.

Only a handful of the 509 miles along the preferred route through Wyoming are complete. A major challenge, Fowler said, is that some regions along the Great American had limited rail systems and sparse populations to begin with. “So we have to look for alternatives, and that’s truly our greatest challenge,” she said. But she’s finding that, when RTC visits towns in Wyoming, Montana and across the county, the message is well-received. “Without question, this is rewarding work,” she said.

Securing funds for the Great American Rail-Trail’s development remains a top priority, especially at the federal level. RTC is also working with states along the route to develop their own funding mechanisms for future trail maintenance. “It’s not enough to build a trail; you have to plan for its future,” she said.

Rider Advice

As it stands, there are many gaps to fill along the Great American. Several western states have triple-digit miles left.

Allison Garrigus rode the Great American with her husband, Alan, as part of the initial Warrior Expeditions trip across the route. They ended up staying in hotels and lodges or with supporters of the project designed to outfit veterans with the gear needed to cross the country on bike. They camped less often than she expected to, she said. Someone who goes into it with that plan could pack a lighter bike. “I will always say less is more,” she said.

“Now that I’ve experienced that dream, it lets me know no dream is unachievable.”

Whitney Washington, Through-Rider on the Great American Rail-Trail

“Take your time and ride your own ride,” advised Whitney Washington. “As the Great American becomes completed, I think it’s good to know that you’ll always find what you need. The trails keep you in nature for a good amount of time, but you’ll also never be too far from stores or bike shops. Well, until you get to Nebraska (coming from the east).”

Said Garrison: “I know everybody has their different level of tolerance. I loved the rugged trails. I loved the sandy trails.” She has fond memories of the Ohio to Erie Trail through Columbus, the Herbert Hoover and Cedar Valley Nature Trails in Iowa, and a rodeo they caught near Fort Robinson, Nebraska. She’d like to forget many of the incomplete stretches that force cyclists to ride on highway roads alongside speeding vehicles. Belle has said experiences like that reinforce the need to fill those gaps sooner rather than later.

Washington said she came away from the ride with favorites, like the Great Allegheny Passage (gaptrail.org) and the C&O Canal Towpath. Montana and Iowa also stood out, she said, but so did the overall process of figuring out how to cross this country on a bicycle.

“It [made] me slow down and look at my options while encouraging me to take more risks … [to learn] that I’ll always find my best way to keep pedaling. To ride my own ride,” said Washington.

This article was originally developed for the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of Rails to Trails magazine. It has been reposted here in an edited format. Subscribe to read more articles about remarkable rail-trails and trail networks while also supporting our work. Have comments on this article? Email the magazine.

2 comments

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.

Can you publish a map?

Thanks

You can view our interactive map of the Great American Rail-Trail on the route page: https://www.railstotrails.org/site/greatamericanrailtrail/content/route/