How Council Bluffs Became the Eastern Point of the First Transcontinental Railroad

In the 1860s, Council Bluffs became the eastern terminus of the nation’s first transcontinental railroad. Today, it’s a linchpin in the 3,700-Mile Great American Rail-Trail.

Just a few months after Council Bluffs, Iowa, became a city—with a name that commemorated a historic meeting between the Lewis and Clark expedition and Otoe Tribe leaders on the bluffs above the Missouri River—a 22-year-old railroad surveyor from Massachusetts named Grenville Dodge arrived in town.

This was autumn 1853, and according to Patricia LaBounty, curator at the Union Pacific Railroad Museum in Council Bluffs, “The city had started to take shape as a western supply depot. If you were going to California, it’s where you stopped before your journey.”

But for Dodge, who had recently completed surveys across Illinois and Iowa for various Midwestern rail lines, Council Bluffs was a destination in and of itself, the perfect homebase for a young man starting a career in railroads. Within months of his arrival, Congress had set aside $150,000 (about $6 million in today’s money) to identify the best route for the nation’s first transcontinental railroad, to stretch from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean.

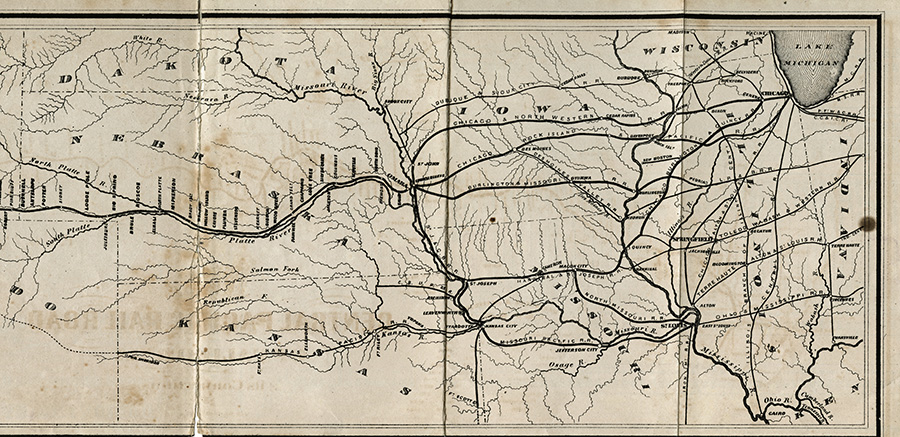

Dodge spent the next five years conducting surveys west of the Missouri River for his employer, the Mississippi & Missouri Railroad, while making a point to interview the other survey parties passing back and forth through Council Bluffs.

Chance Encounter With a Future President

In 1859, Abraham Lincoln arrived in Council Bluffs via steamboat on personal business; however, the former railroad lawyer and future president was newly famous, thanks to his much-talked-about debates with Steven Douglas, and spent his week in Iowa fielding countless invitations to give speeches and attend luncheons held in his honor.

“At some point during the week, he was introduced to Grenville Dodge,” said LaBounty, thanks to the men’s common interest in railroads. “And Dodge writes years later in his autobiography that Lincoln wanted to know everything there was to know about where to put a transcontinental railroad and why. He essentially grilled Dodge for hours.”

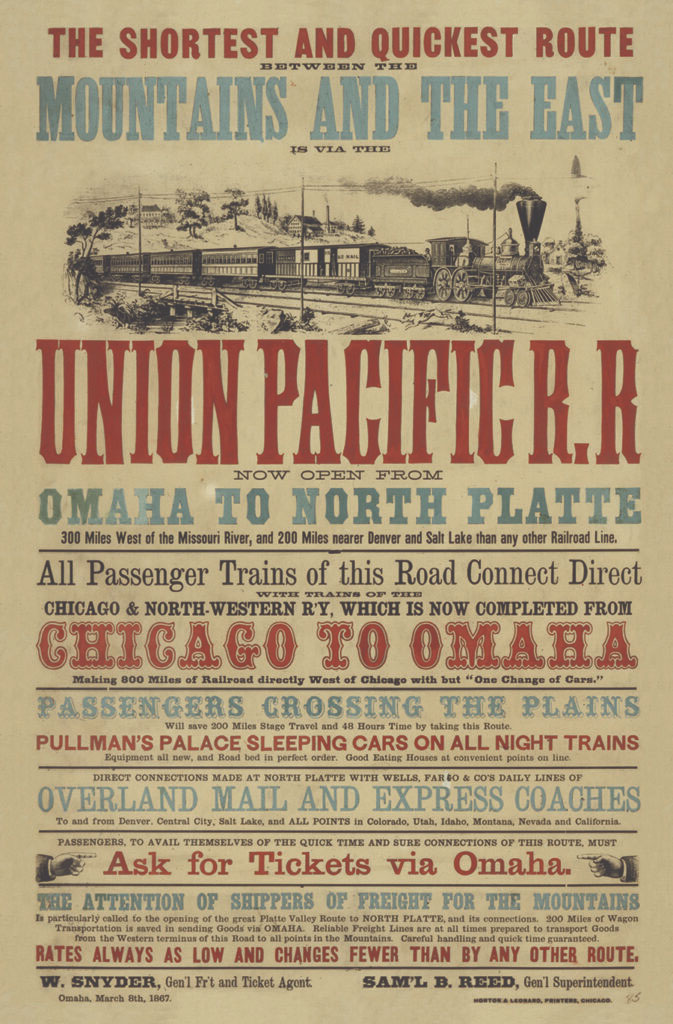

In response, Dodge advocated for a route that would begin in Council Bluffs and follow the Platte River through Nebraska. Railroad tracks required ballast, or rock, for stability—something that was hard to find in the plains but at least possible along a riverbank. Additionally, a steam train would need wood and water to run; again, the river would provide.

The years following their meeting would bring big changes for both men. In 1860, Lincoln was elected the 16th president of the United States, and in 1861, Dodge joined the Union Army as a colonel.

The Pacific Railway Act

By 1863, Dodge, who was then a brigadier general, was stationed outside of Vicksburg, Mississippi, rebuilding railroads and supply lines destroyed by Confederate troops and operating a large spy network comprising Union sympathizers in the south, women and the formerly enslaved.

That’s when Dodge received a message requesting a meeting with President Lincoln at the White House. Initially, Dodge thought he was in trouble for arming freed Black people so they could defend themselves.

“He gets to the White House and spends all day in the waiting area just thinking, ‘I’m dead. They’re going to throw me in jail,’” said LaBounty.

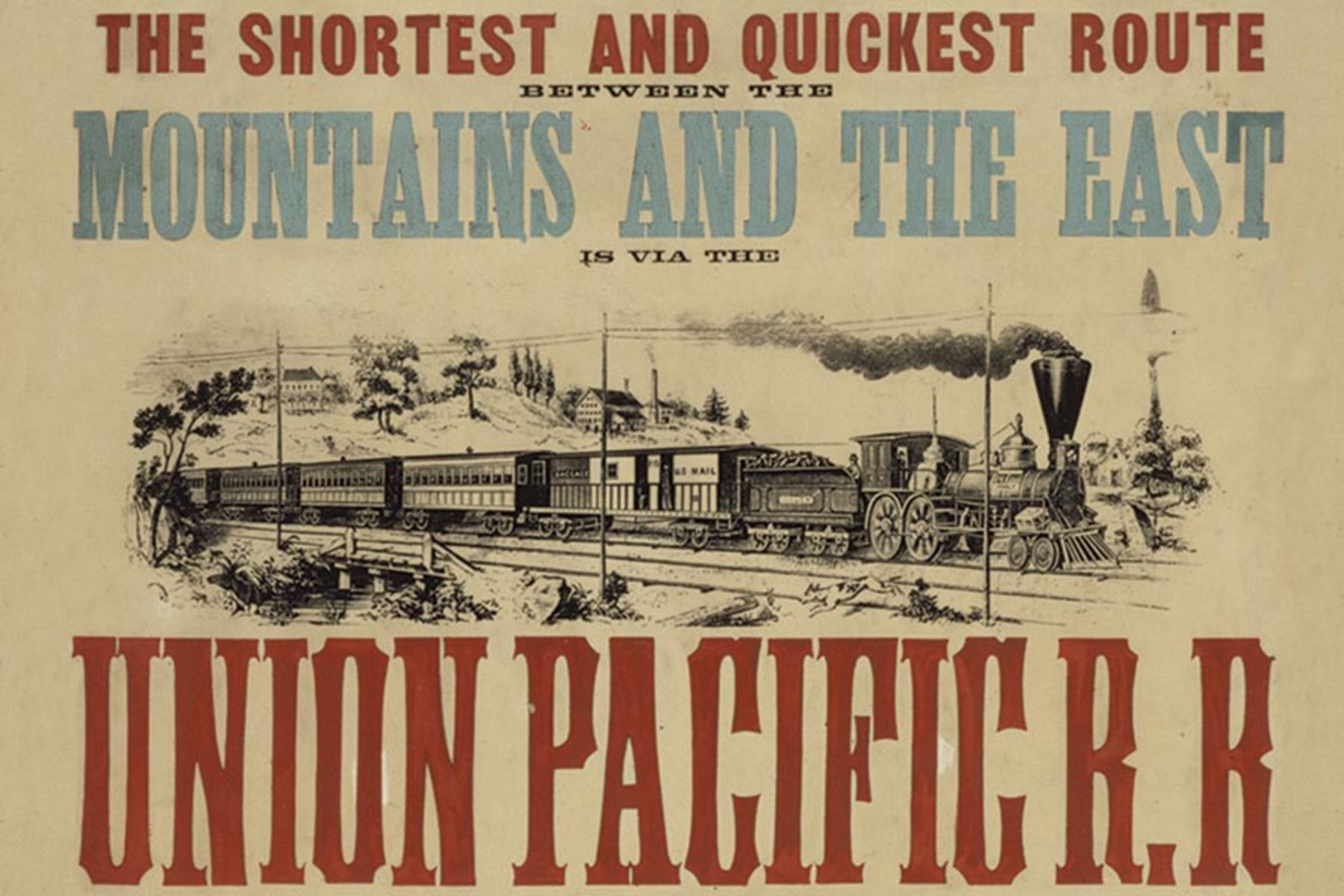

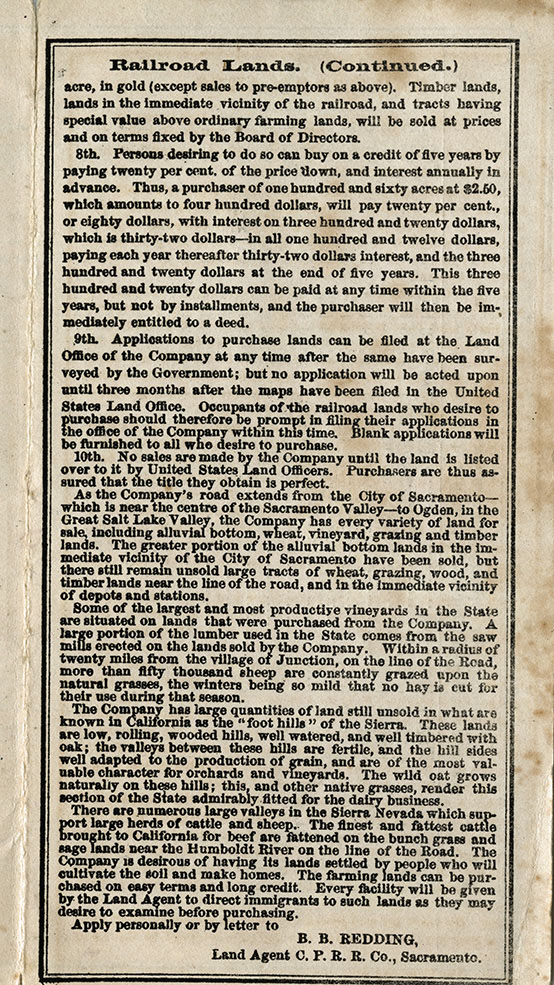

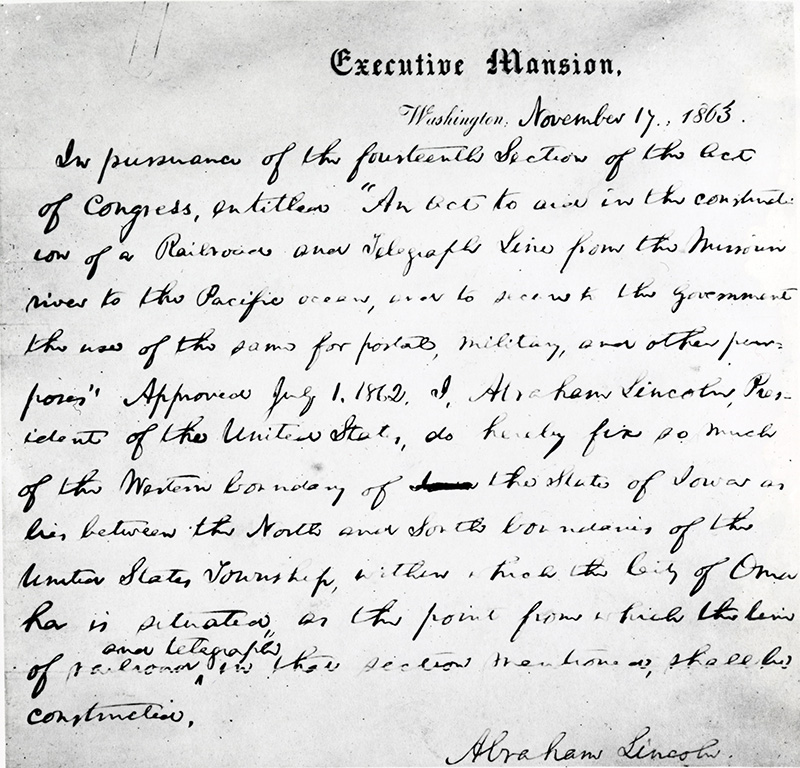

Dodge was relieved to learn the president had instead summoned him for another rap session about the transcontinental railroad. In 1862, Congress had passed the Pacific Railway Act, which created the Union Pacific Railroad Company and authorized it “to construct a single line of railroad from a point on the western boundary of the State of Iowa to be fixed by the President of the United States, upon the most direct and practicable route.” In the year since, Lincoln had been inundated by letters from cities and towns along the Missouri River hoping to be that point.

Dodge again recommended Council Bluffs, and this time, Lincoln agreed. But it would take two presidential orders to get the job done.

Mile 0

According to LaBounty, the first, issued by Lincoln in November 1863, ended up in the pocket of Thomas Durant, vice president of the Union Pacific, who spent the next six months accepting offers from communities who wrongfully thought they were still in the running for the railroad.

“Lincoln is annoyed when he’s still receiving letters,” the museum curator said, “so he finally writes the same order, but this time [he] registers it with congress.”

It worked. On March 7, 1864, Congress officially chose Council Bluffs to be Mile 0 on the nation’s first transcontinental railroad.

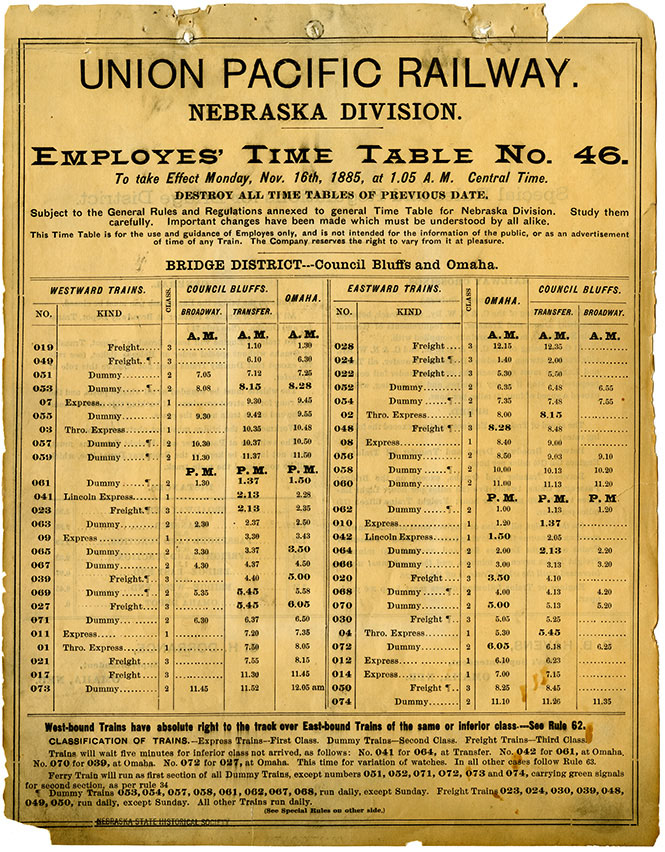

It was a huge win for Council Bluffs,” said LaBounty. “By 1916, the city had seven railroads and nine passenger depots. You could essentially come from anywhere and go anywhere.”

A century later, the railroad tracks are gone, but visitors can still come from anywhere and go anywhere on the recently completed FIRST AVE Trail. The 3.2-mile route in the heart of Council Bluffs traces the Union Pacific’s easternmost stretch of track and provides users with “unobstructed access to our neighbors to the west in Omaha, across the Bob Kerrey Pedestrian Bridge over the Missouri River,” said Brandon Garrett, chief of staff for the city of Council Bluffs.

The FIRST AVE Trail is also a host for the cross-country, 3,700-mile Great American Rail Trail®. When complete, said, Garrett, the Great American will begin a new chapter in Council Bluffs’ rich transportation. “First came the railroad, then the Lincoln Highway, then I-80,” said Garrett. “Now we’ll have the Great American Rail Trail.”

Special thanks to Patricia LaBounty, Curator, Union Pacific Railroad Museum

This article was developed as part of Rails to Trails Conservancy’s Great American Rail-Trail® historical marker program—launched in partnership with the William G. Pomeroy Foundation to lift hidden histories and points of local pride along the 3,700-mile developing route connecting Washington State and Washington, D.C.

A trailside marker, created through a collaboration by the City of Council Bluffs, the FIRST AVE Project, Rails to Trails Conservancy and the William G. Pomeroy Foundation, now commemorates the outcrop.

Marker Location: 99 S. 25th St., Council Bluffs, IA

GATEWAY TO WEST

IN 1863, THIS AREA DESIGNATED

BY PRESIDENT LINCOLN AS EASTERN

END OF FIRST TRANSCONTINENTAL

RAILROAD. UNION PACIFIC BUILT

RAILROAD WEST TO UTAH.

FIRST AVE TRAIL

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2023

Acknowledgments:

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.