Missouri’s Rock Island Trail State Park: Building Miles and Momentum

Growing up in Bland, Missouri, home to about 500 people, Bruce Sassman knows firsthand what the Rock Island Trail State Park will mean to the rural communities situated along its bucolic 144-mile stretch of corridor across the heartland of the state. Incorporated in 1902, the town blossomed with the coming of the Chicago and Rock Island Railroad, at one time supporting a post office, blacksmith shop, mill, general store and church.

“But times changed. The railroad quit running in the 1980s, and the businesses started to close down, one by one,” said Sassman, the elected District 61 Representative in the state legislature. “In my part of the world, we’re all connected by a highway, but we don’t share a whole lot in common. But we’ll be able to ride on the Rock Island Trail between the towns of Bland and Belle and Owensville, and people from one town will be able to go to the next one to get an ice cream cone. I think that’s going to really build some comradery between the communities—adding something to that fiber that holds them together.”

The plans to convert the railbed to multiuse trail solidified in 2015 when the Ameren utility company, who owned it, agreed to donate the corridor to the state. Another boost to the project came in 2023 when the Rock Island Trail came under the auspices of Missouri State Parks, becoming Missouri’s 93rd state park.

Sassman sees potential in Bland along some of the railroad town’s century-old brick buildings that now stand empty on Main Street. “When the Rock Island Trail gets opened up, there’ll be a need for these old buildings; people will want to put them back into service and make use of them, such as entrepreneurs that want to open up their own businesses.”

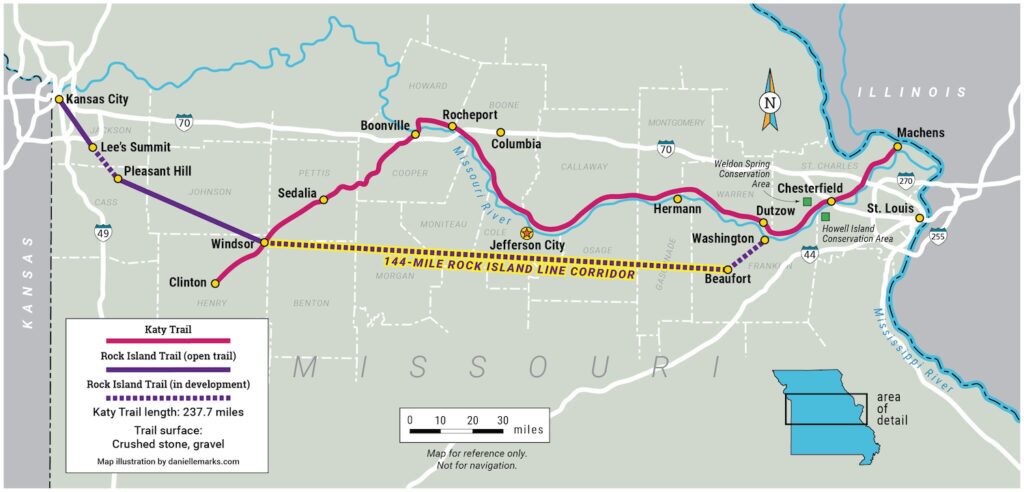

Spanning from Windsor on the western end of Missouri to Beaufort in the east, the 144-mile developing section of Rock Island Trail State Park will eventually connect nearly two dozen communities. (Another 12-mile section will continue the eastward trajectory from Beaufort to Union but will follow an active rail line in a rail-with-trail configuration.)

“Every town is just a little bit different,” explained Chrysa Niewald, a resident of Owensville for almost 50 years and cofounder of Friends of the Rock Island Trail (FORIT). “A lot of the towns came about as a result of the railroad. Owensville and Eldon are the two largest towns; Eldon has about 5,000 people and Owensville about 3,000. Just behind our Main Street is the Rock Island corridor, so the businesses in town are really excited to hopefully capture visitors coming on the trail and staying overnight or visiting different places in the community.”

Notably, a separate 47-mile section of the old railroad corridor—stretching from Pleasant Hill, on the outskirts of Kansas City, to the western end of the undeveloped 144-mile section at Windsor—was converted to a rail-trail in 2016. There at Windsor, the completed and developing segments also connect with another cross-state route, the iconic Katy Trail State Park, which loosely parallels the Rock Island to the north for nearly 240 miles to the outskirts of St. Louis.

When complete, the connected pair would form a trail loop of almost 450 miles—something unique not only to the country, but to the world—and the excitement for how this outdoor tourism duo could bring new economic opportunities to the area, in the short and long term, is palpable.

“What is happening in Missouri will be looked back on in a decade or two as a defining moment in the trail movement,” said Eric Oberg, Rails to Trails Conservancy’s Midwest regional director. “Doubling down on the success of the Katy Trail by developing another cross-state trail, and connecting them into an internationally unique destination, will be remembered as one of the finest projects a state could undertake for the long-term vitality of its smaller rural communities.”

Funding It Forward

It’s perhaps the strong and growing demand for the trail at the local level—from business owners, local leaders and beyond—that has kept the Rock Island project afloat, despite an impasse in the Missouri legislature since 2022 that has prevented funds in the state budget from being allocated for the trail. To that end, residents have embraced the project and are leading the way on their own to see it completed.

“Rock Island Trail communities are not waiting for others,” affirmed Oberg. “They have done everything from self-building sections of trail to taking the lead on federal grant writing. They know what the trail will mean to the vibrancy, resiliency and overall success of their areas.”

Last fall, a master plan for the trail was released by Missouri State Parks after nearly two years of gathering input at public meetings in the communities along the Rock Island corridor. Serving as a blueprint for building the trail, it’s already helped spur two groundbreakings in 2024. Gerald, a small city on the eastern end of the Rock Island corridor, was the first, with a celebratory kickoff for their trail in January. The event was held at Bistro at the Mill, a historical landmark for the community that has been converted into a family-owned restaurant. Nearby Owensville followed suit with a groundbreaking for their 2.5-mile section in April at the City Hall, which sits adjacent to the corridor.

“Gerald used donated funds from individuals; the community really came together to build that mile-long section of trail,” said Ron Bentch, who manages the trail’s development for Missouri State Parks, adding that “there were some children [at the kickoff] who were really excited because the trail will go right past their school.”

And that’s just the beginning. So far, a handful of communities, plus Gasconade County, are infusing the state with new federal money in the form of grants from the Recreation Trails Program and Transportation Alternatives, so progress will continue to ripple through the corridor.

Over $3 million has already been raised to build over 14 miles of the Rock Island Trail State Park. This includes a $250,000 grant for the construction of a 1.4-mile stretch in central Missouri’s Eldon—a gateway to the beautiful Lake of the Ozarks region—that would allow residents to connect to the downtown area, schools, businesses and a park by trail. The project would also entail a new trailhead (including ADA-accessible parking) and the restoration of a historical railroad shed that could be used as a bicycle service center. Another grant of nearly $500,000 will support Gasconade County’s effort to build 2.8 miles of trail continuing Owensville’s stretch of the Rock Island Trail to the Soap Creek Bridge, a 182-foot former railroad crossing west of Rosebud.

“The investment in trail development made by Congress with the passing of the last transportation bill has literally translated to trail on the ground in Rock Island communities, and the return on this investment will last generations,” said Oberg.

A Pathway of Purpose and Promise

In 1990, the first few miles of the Katy Trail opened, followed by a series of more trail openings over the course of two decades. By 2007, it was considered such a wild success that it was inducted into Rails to Trails Conservancy’s Hall of Fame. Today, it draws more than 440,000 visitors a year.

Back in the early 1990s, Kim Henderson worked at a bank in Windsor that had big glass windows looking out at the trail and remembers seeing the bicyclists begin to pass through town. “Windsor is only 16 miles from the west end of the Katy Trail in Clinton, so we weren’t a natural stop for most people. We had a motel a little ways off the trail, but I kept watching and waiting for an opportunity. And then, about 15 years ago, I saw the Rock Island corridor appear on the Missouri State Parks’ map as a dotted line. I thought, ‘If that crosses the Katy in Windsor, that would be huge!’”

Wanting to provide more lodging options for the potential influx of trail travelers as well as for people coming to the area for weddings, family gatherings and other events, Henderson bought an overgrown lot along the trail in her neighborhood a few blocks from Main Street, spruced up the property and opened her first rental cabin there in July 2015. Today, with Windsor serving as a hub for both the Katy Trail and the completed 47-mile section of Rock Island Trail State Park, Henderson’s trailside business, Kim’s Cabins, has grown to four modest log cabins—built by a local Amish carpenter—that are often booked to capacity year-round.

“I’m friends with small business owners up and down the trail,” noted Henderson, who also serves as FoRIT’s vice president. “I’m not going, ‘Your business is too close to me, I don’t want to promote you.’ That would just be silly. The more people that we bring, we all benefit—whether it’s shuttle services, stores, cafés, or coffee shops—we should all work as a team.”

A World-Class Destination—and Local Asset

Communities along the Rock Island Corridor are anticipating how they might replicate the economic success that those along the Katy Trail have had—while embracing the Rock Island’s own unique tourism identity. To draw tourists, some towns are getting creative to develop a distinct identity for their community. In Belle, plans are afoot to create the World’s Largest Cowbell, and in Owensville, the World’s Largest Hotdog Stand is also underway.

“We’re taking a page out of the codebook for the Katy Trail, which says to build the trail in sections that will provide continued interest and enthusiasm, and the motivation for further trail development,” said Rick Mihalevich, vice president of FoRIT, adding that FoRIT is assisting communities with the local matches needed to secure grants.

A notable difference between the two routes is their terrain, making the potential loop formed by their connection that much more enticing; you could enjoy one kind of scenery as you cross the state by trail, then see completely different scenery on the way back. While the Katy Trail largely follows the Missouri River with views of the bluffs along the riverbed, the Rock Island Corridor traverses landscapes that are more rugged and hilly, which also necessitated more of the quintessential railroad features that rail-trail buffs love.

“The Rock Island has big trestles and tunnels, native grassland prairies, rolling hills, clear streams and big rivers—it would give you a taste of Missouri that no other trail could,” explained Mihalevich.

Mihalevich lives in Jefferson City, which he describes as the “pinch point” between the Rock Island and Katy trails—so close that he envisions connecting the two in the middle of their routes in addition to their endpoints, forming two interior loops as well as the big one.

Nestled in the foothills of the Ozark Mountains, some of the Rock Island’s features—the ones that Ron Bentch calls the “Big 5”—are anticipated to be the most challenging to refurbish but also the most spectacular. They include the Gasconade River Bridge, the trail’s longest bridge spanning 1,771 feet; the Euguene Tunnel, the longest of three tunnels along the trail at 1,665 feet; the Osage River bridge; the unlined Argyle Tunnel, which feels like a cave; and the Freeburg Tunnel.

But there’s another important distinction between the two trails. “The majority of the Katy Trail is next to the Missouri River, so it hits the edges of towns,” explained Bentch. “Whereas the Rock Island goes right past downtowns and schools, so the trail is seen by many communities as a safe route to school and a transportation option.”

Having worked for many years as a high school geography, history and social studies teacher, as well as an assistant principal, Niewald understands the value of having trail connections to schools. “The school buildings in our district are not accessible by sidewalk, because we don’t have a lot of sidewalks and you have to cross a highway. So here in Owensville, kids cannot ride their bikes or walk to school. And it’s pretty much similar to that in most of our communities.”

With the trail paralleling literal Main Streets in most of these towns, it will serve the same purpose as that major thoroughfare—connecting schools as well as workplaces, stores and other important destinations—but in a safer and more pleasant way for pedestrians and bicyclists. With such tangible improvements to residents’ quality of life in terms of transportation, economic and health benefits now on the cusp of being realized, support for the project has steadily grown in the communities along the route.

As Oberg stated, “Communities are excited, and now they just need the support to fast-track development.”

Good Neighbors

Trail advocates plan to focus on connecting communities at each end of the Rock Island corridor first—where enthusiasm for the project is highest—and then work their way toward the middle. The eastern section, stretching between Gerald and Belle, will span 24 miles; the western section, between Versailles and Eldon, will cover 18 miles. But much of the corridor’s 144-mile length runs through farmer-owned land, where there has been mixed support for the trail.

“There are two of us at state parks working on this project, and we both grew up on farms,” explained Bentch, whose hometown is Versailles, one of the Rock Island communities. “So we’re really trying to understand the concerns of farmers and come at it with an empathetic approach, because we know that these are going to be our neighbors for a long time.”

Bentch even lists his cell phone number on the state parks website and aims to respond to calls within 48 hours. “There are a lot of different value systems across the trail, so I try to listen and understand and find solutions,” said Bentch.

For Henderson, who grew up on a couple acres outside of St. Charles on the eastern end of the state—and lived close to either the tracks or what is now trail for most of her life—the Rock Island project is “near and dear” to her heart. She has no doubt it will happen. “It’s going to take a while, so it just takes patience.”

She added, “I keep using the word ‘iconic’ for this trail, but I truly believe it will be.”

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.