American Dreams: People Who Shaped the Landscape of the Great American Rail-Trail

America has long been a land of big dreams and big dreamers—and sometimes when they come together, they leave an indelible mark on the landscape.

It’s in recognition of this that Rails to Trails Conservancy launched History Along the Great American Rail-Trail® on TrailLink™, a project exploring the people, places and events that shaped the cultural fabric of communities along the 3,700-mile route. “When moving through space along a trail, you are also moving through time,” said Avigail Oren, the project’s lead, in a 2021 interview, adding that there’s so much “potential to use place—along this very diverse route—as a way to make these stories visible.”

Here we look at a handful of such stories.

Historical Marker Program

From tracing the eastern terminus of the nation’s first transcontinental railroad, to remembering a renowned U.S. Civil War veteran from China, to highlighting a rare geological unconformity with origins hundreds of millions of years old, the Great American Rail-Trail® encompasses 3,700 miles of the country’s rich history. In partnership with the William G. Pomeroy Foundation, RTC is lifting up these hidden stories through the Great American Rail-Trail historical marker program. Learn more about the histories of these markers, which are popping up at 12 sites along the Great American.

Civil War Veteran Edward Day Cohota & Nebraska’s Cowboy Recreation and Nature Trail

When Edward Day Cohota claimed to be the only Chinese soldier serving in the Union Army, it’s understandable that he believed this statement to be true. While more than 3 million men fought in the Civil War, a mere 58 of them are thought to have been of Chinese descent.

Underfed and sickly, the 4-year-old Cohota and his elder brother were found orphaned in the port city of Shanghai and taken in by Sargent S. Day, the captain of the merchant ship Cohota. It’s from his adopted father’s surname, and the name of the ship that brought him to America, that the boy took his English middle and last names.

Although his brother soon died, Cohota was raised in Gloucester, Massachusetts, by the Days, alongside the couple’s two biological children. A teenager when the Civil War began, Edward enlisted in the Union Army and survived without serious injury, though one battle left his clothes bullet-torn and his hair permanently parted from where a bullet had grazed his skull.

Cohota’s 30-year U.S. military career took him to the western plains of Dakota Territory, where he met and married Anna Dorothea Hallstenson in 1883. He retired from the army in 1894 and opened the Kangaroo Restaurant in Valentine, Nebraska. Believing he was a naturalized citizen—foreign-born soldiers were offered citizenship in exchange for fighting—he applied for a grant of land in 1912 under the Enlarged Homestead Act, only to discover that the appropriate paperwork was never filed. He was not a citizen, and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 made it impossible to become one. Cohota spent years unsuccessfully petitioning Congress to intervene.

Today, Nebraska’s Cowboy Recreation and Nature Trail, one of the country’s longest rail-trails, passes by Mt. Hope Cemetery in Valentine, where Cohota was laid to rest in 1935.

Civil Rights Activist Dorothy Height & Pennsylvania’s Great Allegheny Passage

While just half a square mile in size, the borough of Rankin outside of Pittsburgh was nonetheless an industrial powerhouse in the early 1900s, being home to a multitude of blast furnaces and factories. It was to here that Dorothy Height’s family moved from Richmond, Virginia, in 1916 when she was 4 years old. And with a mother active in the Pennsylvania Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, an early interest in social justice took hold.

Height was an enthusiastic participant in the local YWCA and was even elected president of the club, but was appalled to learn that the color of her skin barred her from swimming at the central YWCA branch. “I was only 12 years old. I had never heard of ‘social action,’ nor seen anyone engaged in it, but I barely took a breath before saying that I would like to see the executive director,” Height related in her 2003 memoir.

Having graduated with a master’s degree from New York University in 1933, Height worked as a community leader, civil rights activist and executive with the national YWCA, eventually landing a role as president of the National Council of Negro Women in 1957. Over the course of her 40 years in that role, Height championed expanded political and economic opportunities for Black women.

Today, the 150-mile Great Allegheny Passage (gaptrail.org) passes by Height’s childhood hometown of Rankin and provides a nearly continuous path for the Great American through Pennsylvania.

This article was written as part of History Along the Great American Rail-Trail®, a project highlighting hundreds of stories and historical points of interest along the 3,700-mile route. It was originally published in the Spring/Summer 2024 issue of Rails to Trails magazine and has been reposted here in an edited format.

By Scott Stark, with contributions by Avigail Oren and Nicole Friske

Singer Mildred Bailey & Washington’s Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail

Mildred Bailey was born in 1903 and grew up on Idaho’s Coeur d’Alene Reservation, where her mother was an enrolled member of the tribe. Bailey’s great-grandfather, Bazil Peone, was the head speaker and song leader of the tribe’s people, and her parents were both proficient musicians, so she was no stranger to the musical traditions of her ancestors.

It should be noted that while the name “Coeur d’Alene” was given to the tribe in the late 18th or early 19th century by French traders and trappers, members refer to themselves in their native language as Schitsu’umsh, meaning “The Discovered People” or “Those Who Are Found Here.”

Bailey’s grandfather had created a music style that blended European hymns brought by Jesuit missionaries with the language and melodies of Schitsu’umsh songs, and when Bailey got involved in the jazz scene, she incorporated those musical traditions with a vocal technique that set her apart from other singers.

Throughout the 1920s, her voice could grab the attention of any Prohibition-era speakeasy crowd, and her personality and musical virtuosity earned her the admiration of fans and musicians alike—including one up-and-comer named Bing Crosby, whose career she helped launch. By the 1930s, Bailey was being broadcast nationally on the radio as a soloist and was performing with Paul Whiteman’s orchestra, making her one of the first women to front a big band. Unfortunately, health complications led to her early death in 1951, but not before “The Queen of Swing” brought the unique melodies and rhythm of the Schitsu’umsh style to the ears of millions.

Today, the Palouse to Cascades State Park Trail, one of the nation’s longest rail-trails, passes through Tekoa, Washington, where Bailey was born.

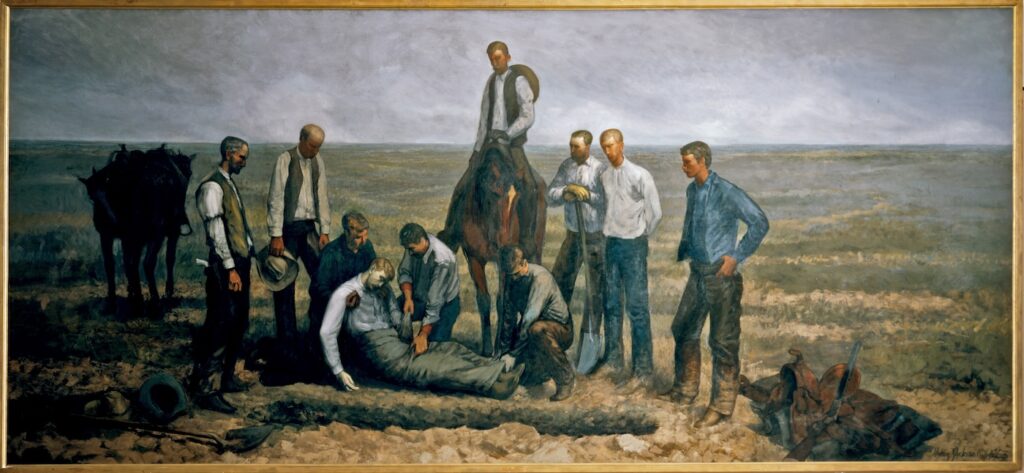

Artist Harry Jackson & Wyoming’s Beck Lake Bike Park Trails

As a child in Prohibition-era Chicago, Harry Jackson had two driving interests: drawing and horses. Weekend classes at the Art Institute of Chicago as a young teen furthered his interest in art, and the cattlemen he met working at a lunchroom in the city’s stockyards fueled his passion for all things Western. A photo spread on cowboys in Life magazine was the final push; in 1938, at the age of 14, he hitchhiked his way westward to Wyoming and found work as a ranch hand outside the small town of Meeteetse, which he came to call his “spiritual birthplace.”

For four years he overwintered back in Chicago, where he furthered his art education before enlisting in the Marines and becoming a combat artist with the Fifth Amphibious Corps. After earning two Purple Hearts, he was discharged at the end of World War II and suffered from post-traumatic stress disorder for the rest of his life. The work of abstract painter Jackson Pollock had a profound effect on the veteran, who recounted that one painting in particular “shot the first crack of daylight into my blocked-off brain; that single artwork caused me to relive [the Battle of] Tarawa’s bloody butchery; I knew that I had to meet Pollock face to face ASAP.”

After moving to New York City, befriending Pollock and adopting his style of abstract expressionism for a few years, Jackson gained a following before transitioning to realism and beginning the body of Western-themed work that includes the sculptures he is best known for today. Poetically, he was featured in an eight-page photo essay in Life.

By 1980, Jackson was one of the wealthiest artists in America, but even with his work in major art institutions, Jackson noted that having much of his work collected in Wyoming “means more than being lauded around the world.” Today, the Buffalo Bill Center of the West in Cody, Wyoming, houses the largest collection of his work in the United States. Much of Wyoming’s Great American route has yet to be developed, but you can experience a short section on the 2-mile Beck Lake Bike Park Trails, which circle Cody’s reservoir.

Looking for more history stories?

- How Council Bluffs Became the Eastern Point of the First Continental Railroad

- First in Class: Washington Trailblazer Clara McCarty Wilt Was UW’s First Graduate

- Awaiting Takeoff: The Wright Brothers’ Biking Legacy

- Remembering the Chinese Forerunners Who Built the Northern Pacific

- Taters and Trains: The Great Big Baked Potato and the Northern Pacific Line

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.