For Some 60 Years, Peru, Indiana, Was America’s “Circus City”

Peru is known as the Circus Capital of the World for a big reason. It really was.

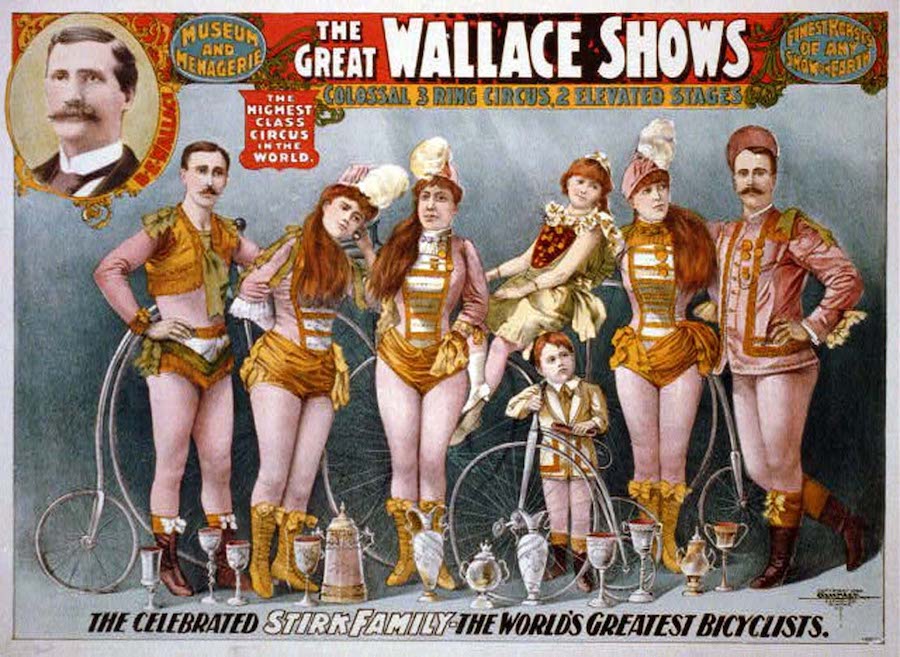

Starting in 1884 when a Livery Stable owner named Ben Wallace took his first circus on the road, Peru began a circus winter quarters legacy that would last 60 years.

Wallace had huge success with his circuses; within the first two years of establishing himself, he had gone from a traveling horse and wagon show out of his farm on Route 124, about 6 miles east of Peru, to moving across the country on rails.

Peru was a major railroad hub in the second half of the 19th century, specifically for the Peru and Indianapolis Railroad, which now serves as the right-of-way for the 40-mile Nickel Plate Trail connecting Fulton, Howard and Miami counties. The hub was so big, they even had a roundhouse to work on the many railroad cars and engines. It just made sense to move the circus by trains in 1886, with all the rail support in Peru.

By 1892, Wallace had established a new winter headquarters, just off Route 124, to house his growing cadre of animals and performers. With the purchase of over 200 acres of fertile farmland along the Mississinewa River from Chief Gabriel Godfroy of the Miami Indian nation, Wallace could now maintain circus winter quarters closer to the town of Peru with much more space to house his circus empire.

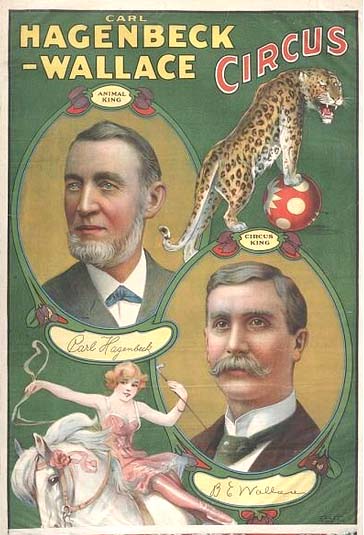

Wallace grew his circus to the point that by 1904, he started his own bank. The Wabash Valley Bank and Trust served his needs on the corner of Main Street and S. Broadway Ave., where a CVS Pharmacy is now. The third floor became the circus wardrobe department, where seamstresses could work in town all winter making new costumes and animal blankets. In 1907, Wallace bought the defunct Carl Hagenbeck Trained Wild Animal Circus. Adding 13 elephants to his growing circus and doubling the wagons and train cars, this mega-operation became known as the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, a popular show that was rivaled by only Ringling Bros. World’s Greatest Shows and another circus on the East Coast known as Barnum & Bailey’s Greatest Show on Earth.

Things weren’t always good for the circus. Even though the massive 1913 floods in the area tragically killed all his wild animals, including the elephants, Wallace still pulled it together and went back on the road in April. He then sold his entire circus in June to John O. Talbot and Edward Ballard.

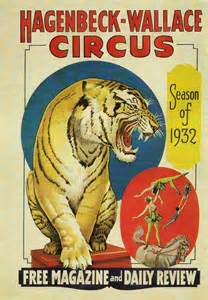

Wallace had many friends in the circus business, and two of them, Jerry Mugivan and Bert Bowers, made use of the Peru circus winter quarters for their own circuses for the next several years. By 1918, Mugivan and Bowers had two circuses on the road and had also acquired Wallace’s beloved Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus. In 1920, they added to their collection again, purchasing the Sells-Floto Circus out of Denver, Colorado, and the Yankee Robinson Circus, which traveled the Midwest.

In 1921, Mugivan and Bowers created the American Circus Corporation along with a hotel owner named Ed Ballard. They bought the Peru circus winter quarters and started the huge expansion of buildings in 1922. With 42 different buildings being used to house this circus conglomerate by 1929, it was by far the largest circus winter quarters in America. Fifty elephants called Peru home, and more than 150 different railcars were sitting in the train yards every winter.

The circus was very competitive. The American Circus Corporation was yielding five different circuses across America, and John Ringling of the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus couldn’t stand it. He came to Peru in August to discuss this competition and come to an agreement. The eventual $1.7 million deal that resulted yielded him all of Peru’s winter quarters, circuses and titles, making Ringling the magnate of the circus empire. Six weeks later, however, the stock market crashed—the Great Depression began to set in—and Ringling’s empire began to spiral downward.

Ringling closed a circus a year, slowly eliminating his competition to make the Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus as profitable as possible. The last Ringling-controlled American Circus Corporation circus to go out of Peru was the Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, in 1935. In 1937 and 1938, it was leased to others, collapsing altogether in 1938 on the west coast. The Ringling Circus also closed in June of 1938 with major labor problems—leaving one Ringling circus remaining, the Al G. Barnes-Sells-Floto Circus, which was based in Culver City, California.

After taking some of the biggest Ringling attractions to that circus to finish the 1938 season, the Peru circus winter quarters was finished as a working circus home. The property, comprising hundreds of acres of fertile farmland, was sold to Emil Schram, a Peru native and the head of the New York Stock Exchange in 1944.

Today, the property at 3076 E. Circus Lane in Peru–about 5.5 miles from Peru’s trailhead for the Nickel Plate Trail–is a National Historic Landmark and the home of the International Circus Hall of Fame.

Special thanks to Robert Cline, historian for the International Circus Hall of Fame, for contributing this story.

This article was developed as part of Rails to Trails Conservancy’s Great American Rail-Trail® historical marker program—launched in partnership with the William G. Pomeroy Foundation to lift hidden histories and points of local pride along the 3,700-mile developing route connecting Washington State and Washington, D.C.

A trailside marker, created through a collaboration by the Nickel Plate Trail Inc., Rails-to-Trails Conservancy and the William G. Pomeroy Foundation, now commemorates the outcrop.

Marker Location: 0.7 mile north of E. Market St., Marshallville, OH

“CIRCUS CITY”

FROM 1892-1941, PERU

SERVED AS WINTER HEADQUARTERS

FOR SEVERAL AMERICAN CIRCUSES,

HOUSING PERFORMERS, ANIMALS

AND CIRCUS EQUIPMENT.

NICKEL PLATE TRAIL

WILLIAM G. POMEROY FOUNDATION 2023

Acknowledgements:

- Friends of the Nickel Plate

- International Circus Hall of Fame

- Nickel Plate Trail Inc.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.