End of the Line: How Timber and Train Tracks Transformed the Olympic Peninsula

At the end of the 19th century, as transcontinental railroads began crisscrossing the country, connecting people and buoying economies, residents of Washington’s Olympic Peninsula looked on with envy. Around them stood some of the tallest, most valuable timber in North America. A constellation of shoddy, narrow-gauge railroads and barges carried felled trees to the mainland, but the system was a far cry from the efficiency and speed—not to mention the fortune and prosperity—a transcontinental connection would bring.

In the peninsula’s largest city, Port Angeles, rumors of the railroad’s arrival ran rampant. In 1873, when the Northern Pacific chose Tacoma as its western terminus, the disappointment was stinging.

“For decades, people would say, ‘It’s coming! It’s coming!’” said Margaret Owens, curator at the Joyce Depot Museum in Joyce, Washington. “And then, ‘Oh, it’s not coming. It’s not.’”

In the 1880s, antsy locals took matters into their own hands, establishing their own railroad company. The resulting endeavor laid a grand total of 1 mile of track.

In nearby Port Townsend, another group of citizens pledged more than $100,000 to a trust fund intended to lure a railroad to town. The gambit worked, attracting the attention of multiple rail companies. Less than three years and 27 miles of track later, however, the company building the new railroad went bankrupt, and the town’s ambition to become a rail hub was dashed once again.

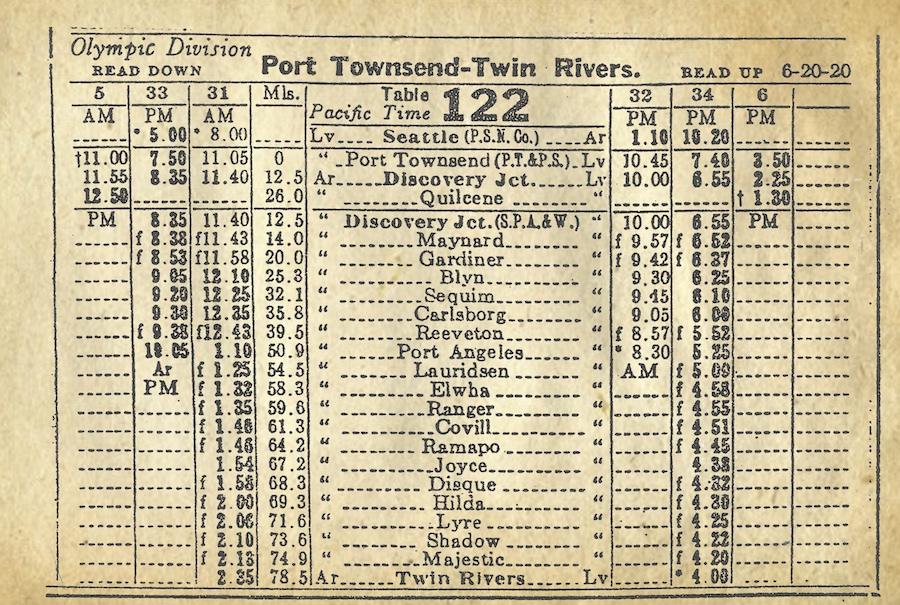

At last, in 1914, a long-awaited railroad arrived on the Olympic Peninsula in the form of the Seattle, Port Angeles and Western Railway, which was rapidly acquired by the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul and Pacific Railroad, the nation’s final transcontinental line, completed in 1909. The Milwaukee Road, as it became known, quickly bought up the myriad tracks that had been laid over the last few decades “to get some of that big, tall timber,” according to Owens, “and start the money rolling.”

The “Farthest West Railroad” Carried Timber and Tourists

Before the railroad’s construction, most development on the Olympic Peninsula was concentrated along its northern shore, where the land met the cerulean water of the Strait of Juan de Fuca. There were few inland roads or settlements, and people relied on steamboats to ship and receive goods from larger cities across Puget Sound. But as soon as they were sure the Milwaukee Road’s arrival wasn’t just another rumor, residents began a mad dash to set up shop next to the line.

“The train was the future. People willingly dragged everything—houses, businesses—from the beach to where the tracks would be laid,” stated Owens. “They said, ‘Forget about the steamers, let’s get to the train!’”

In short order, the first train cars of fresh-hewn logs began heading for the mainland. But the Milwaukee Road carried more than timber. By 1915, tourists from Seattle could get to Port Angeles in a single afternoon while enjoying an exceptionally scenic train and ferry ride.

“The railroad began advertising to tourists,” explained Owens, luring passengers aboard with the promise of world-class fishing and resorts that had popped up around the peninsula’s natural hot springs. In the tiny town of Joyce, the depot was built in the style of a log cabin meant to charm arriving tourists. “It’s yellow and green and very cute,” Owens said.

While some structures along the country’s westernmost railroad were designed to evoke whimsy, others exemplified modern engineering. For example, the 730-foot Dungeness River Bridge, built on the outskirts of the town of Sequim, employed the use of a Howe truss design and incorporated both steel and wood.

“These bridges were good for longevity. They’re not easily damaged, and they last a long time,” said Ken Wiersema, a board member for the Dungeness River Nature Center, which sits adjacent to the old bridge. “It’s an iconic structure in this part of the country.” Today, it’s one of the last remaining Howe trusses in the state, and a prominent structure of the developing Olympic Discovery Trail.

In 2015, when a severe flood caused structural damage to the bridge, the Jamestown S’Klallam Tribe—who now owns it—constructed a new, environmentally friendly steel and concrete trestle while maintaining the historic truss. Last year, the tribe took on an even more ambitious repair project, removing one of the bridge’s levees to restore the river’s original floodplain as well as vital habitat for breeding salmon.

“It was a huge win,” said Jamestown S’Klallam Chairman W. Ron Allen. “One, for the [Olympic Discovery] Trail, two, for the bridge and three, for the salmon.”

A Labor Strike, a World War and a Government Scandal

In the spring of 1917, when the United States officially entered World War I, the Pacific Northwest was already supplying timber to support airplane production in Britain and France. In the Olympic Peninsula, virgin stands of Sitka spruce were tapped to build some of the world’s fastest and most resilient airplanes, lightweight but impenetrable to bullets.

Just as demand for the wood skyrocketed, a labor strike hobbled the timber industry. Led by the union Industrial Workers of the World, loggers and lumberjacks went to the picket line, demanding safer conditions, better wages and an eight-hour workday. Production plummeted, risking the Allies’ success on the warfront.

To remedy the dire situation, the War Department sent Colonel Brice Disque to the Pacific Northwest to spend time with striking workers, mill owners and union leaders in an attempt to get production moving again. After five months on the ground, Disque didn’t see a compromise in the cards. Instead, he recommended that the Army simply take over production, nationalizing the timber industry. By November 1917, Disque had been given command of the newly formed Spruce Production Division (SPD), a part of the United States Army Signal Corps. At its peak, the SPD employed more than 30,000 soldiers.

At first, both management and labor were skeptical of government intervention; however, Disque had a plan that would appease both parties. The presence of troops allayed worry by mill owners about labor shortages, while the Army’s workplace conditions—including the much sought-after eight-hour workday—began to normalize the demands workers had been making.

To inspire camaraderie, Disque sponsored an alternative union founded on patriotism and national defense. The new union, the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen, would persist two decades after the war ended.

With labor woes settled, Disque and leaders of the SPD then turned their attention to production and how to harvest enough timber to meet ever-growing demand, which meant building more mills and more railroads.

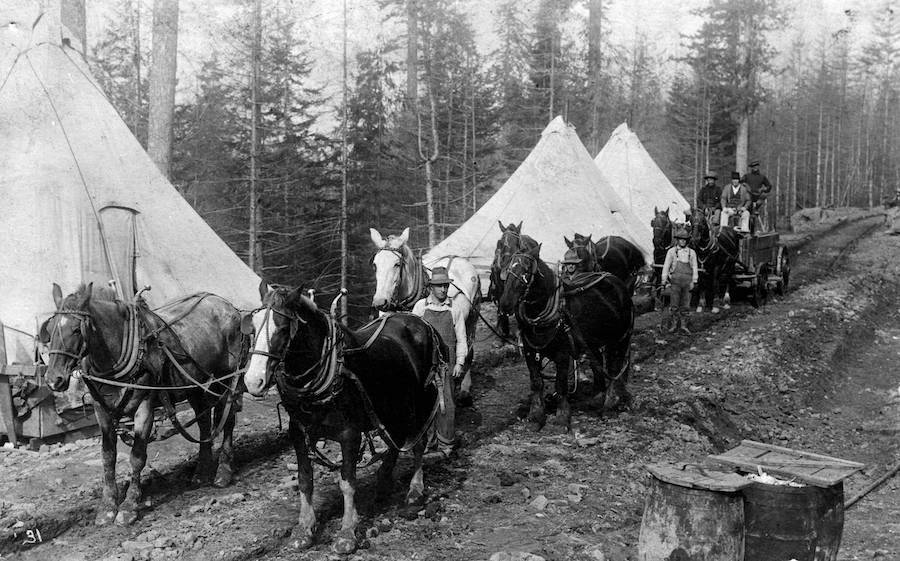

On the Olympic Peninsula, the SPD invested $10 million to build a 37-mile spur from the Milwaukee Road at Joyce. Men worked all day and all night, in all kinds of weather, to lay the Spruce Railroad—which included two bridges, two tunnels and a telegraph line—at an astonishing pace. “[The SPD] mobilized people, cut the tunnels, put the line through in a year,” said Wiersema.

Unfortunately, all that breathless, painstaking work was for naught. Within weeks of the Spruce Railroad’s completion, the Armistice was signed. The war—and the SPD—were over.

The controversy surrounding the railroad, though, was just beginning. Allegations swirled that the contractors who built the railroad had mismanaged the project, and that the expensive route had been chosen to benefit industry when mere logging roads would have sufficed.

In 1919, a congressional committee convened to investigate the project. “The line was built not to carry spruce logs, but as an extension of the Milwaukee Railroad for commercial purposes,” the committee concluded. “We would rather see this railroad and mills scrapped than to have the government sell it … for an insignificant percentage of its cost.”

Nevertheless, page 22 of the June 28, 1919, edition of The New York Times featured an unusual listing: “Sale: A permanent railway system tapping large virgin areas of timber and a well-located modern sawmill of large capacity.”

Olympic Discovery Trail

A host trail of the developing 3,700-mile Great American Rail-Trail®, the Olympic Discovery Trail will one day stretch 138 miles, from Puget Sound to the Pacific Ocean, in many places following the railbeds of the Milwaukee Road and Spruce Railroad. The Port Townsend waterfront marks the eastern endpoint of the Olympic Discovery Trail; halfway to the town of Port Angeles, trail users can cross the iconic Dungeness River Bridge and stop into the nearby nature center.

Fifteen miles west of Port Angeles is Joyce, home of the Joyce Depot Museum, where tourists used to arrive by the trainload from Seattle. Here, the trail turns south and follows the Spruce Railroad toward Lake Crescent and Olympic National Park, passing below the towering Sitka spruce trees that helped the Allies win World War I.

This section of the Olympic Discovery Trail currently ends at the western boundary of Sol Duc State Park. The Peninsula Trails Coalition is working to extend the trail west through Forks and to the coastal town of La Push.

Related: Read more about the Olympic Discovery Trail in our Spring/Summer 2021 cover story.

Saying Goodbye to “That Rickety Old Train”

By the middle of the 1900s, traffic on both railroads was winding down. The Milwaukee Road’s tourism push was waylaid by the 1931 completion of the Olympic Loop Highway, which made visiting the area by automobile quick and easy.

“The train only came through twice a day. The bridges had become drinking spots and swimming holes,” remembered Wiersema. “It had outlived its time.”

As repeated presidential orders expanded the boundaries of Olympic National Park, tracts available to the timber industry shrank. By the 1970s, only 5,000 carloads a year ran across the peninsula. The need for rail transport continued to decline as more and better-quality logging roads were built.

“Log trucks were ready to take the place of that rickety old train,” said Owens.

In 1987—just a century after residents in the two towns had hoped, prayed and fundraised for a railroad of their own—the tracks between Port Angeles and Port Townsend were removed for good.

This article was originally developed for the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of Rails to Trails magazine. It has been reposted here in an edited format. Subscribe to read more articles about remarkable rail-trails and trail networks while also supporting our work. Have comments on this article? Email the magazine.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.