Remembering the Chinese Forerunners Who Built the Northern Pacific

This article was written as part of History Along the Great American Rail-Trail®, a project of TrailLink.com™, highlighting hundreds of stories and historical points of interest along the 3,700-mile route. It was originally published in the Winter 2023 issue of Rails to Trails magazine and has been reposted here in an edited format. Have comments on this article? Email the magazine.

Acknowledgments: The article includes contributions from Avigail Oren.

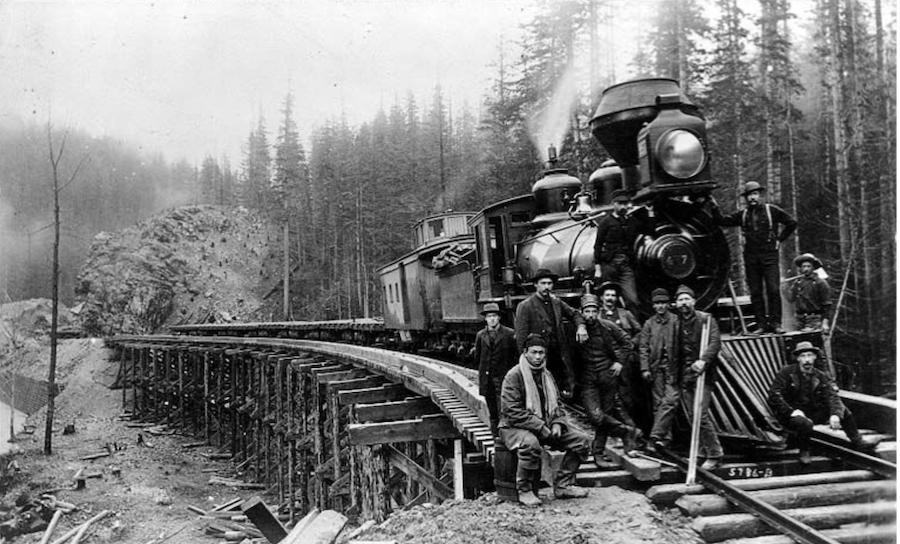

On Aug. 22, 1883, the final tracks of the Northern Pacific Railway were laid when a Chinese crew from the West met an Eastern crew of mostly Irish and Slavic workers near Independence Creek, Montana. It was the country’s fifth transcontinental line—stretching from St. Paul, Minnesota, to Seattle, Washington—and like the others, it was built largely by immigrant hands.

It had been 14 years since the final spike of the first transcontinental railroad was driven in Promontory Point, Utah, an event so momentous that the hammering of the spike was broadcast nationwide via telegraph wire. In that time, demand for railroads—for a way to transport people and goods across the continent—had continued to swell; unfortunately, so did the era’s xenophobia and nativism.

“It was a challenging life. Community was so important.”

—Dr. Robert Bauman, History Professor, Washington State University Tri-Cities

In the Pacific Northwest, the Chinese crews who built the Northern Pacific line endured backbreaking labor on top of an increasingly hostile sentiment toward immigrants, but they would rely on each other to make it through, and today, their contributions are remembered. “It was a challenging life,” said Dr. Robert Bauman, history professor at Washington State University Tri-Cities. “Community was so important.”

While many of the Chinese left the region or even the country after completing work on the Northern Pacific, due to strict anti-immigration laws passed during its construction, their legacy lives on in cities and towns along the line and in stories still told by their descendants.

Looking for a Better Life

Initially, the Chinese came to the American West for the same reason that so many others did: dreams of gold. “We think of the Gold Rush as a national phenomenon, but it was an international event,” Bauman said.

In the mid-19th century, life in China was difficult and violent, marked by war, famine and poverty. When word came in 1849 that gold had been discovered in California, a lot of Chinese people—mostly men—made the voyage across the Pacific Ocean. “The plan was to work for a few years, strike it rich, and go home. Mostly, it didn’t work out that way,” according to Bauman.

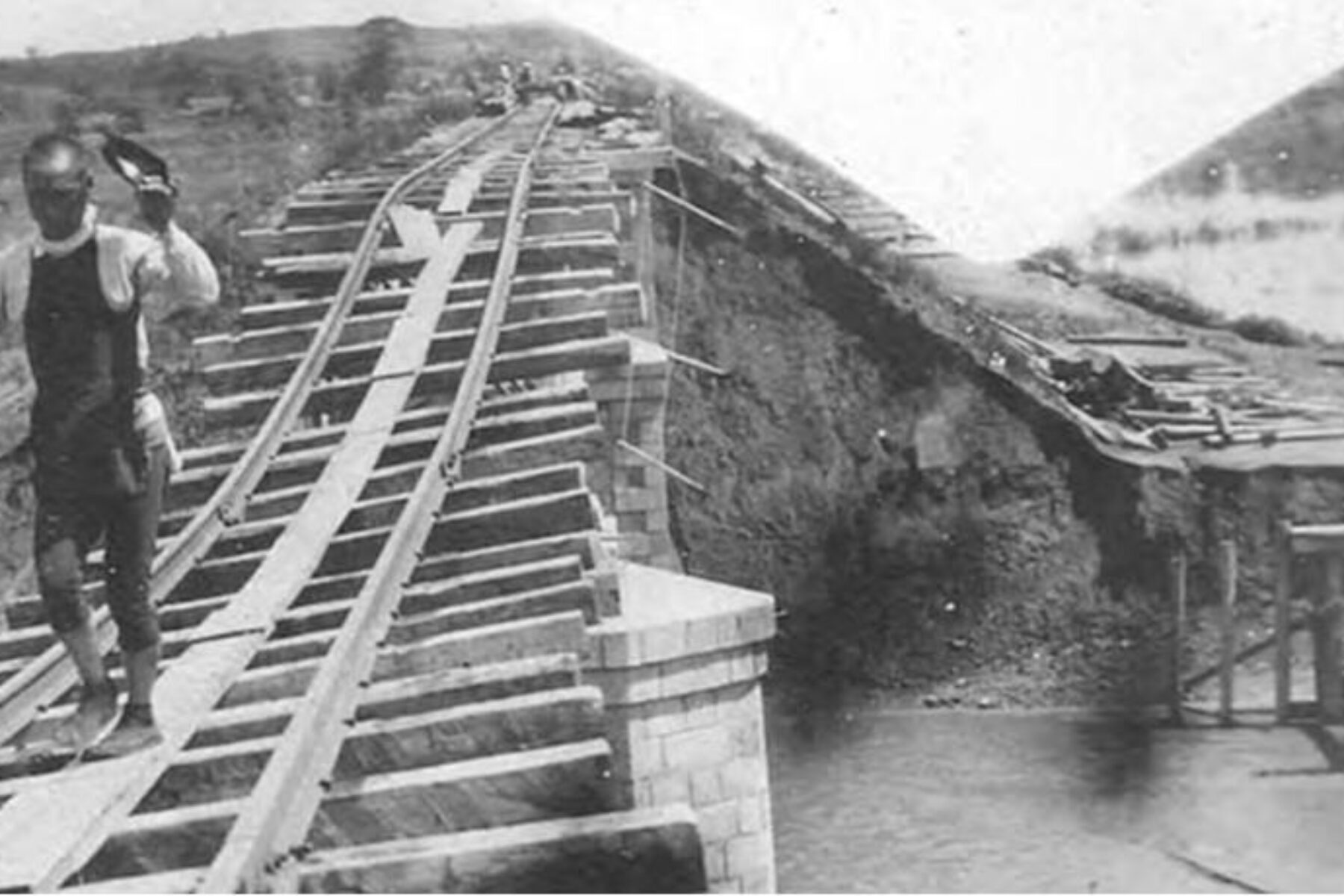

Instead, as the gold dried up, many Chinese found jobs working on railroads. Historians estimate that as many as 15,000 Chinese immigrants were involved in the construction of the Central Pacific, the first transcontinental line. They moved earth, bored tunnels, built retaining walls and laid track—completing virtually all of these grueling tasks without the aid of machinery or power tools. Despite working longer hours than their white counterparts, Chinese laborers made on average about half to two-thirds in wages.

Many of the men sent every extra dollar they could save back home to China. “So many people were counting on him,” Vicki Tong Young said about her great-grandfather Mok Chuck in an interview with Stanford’s Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project, a comprehensive collection of historical documents and oral histories on the subject. “Not only was he providing for himself and his family, but also the people back” in his ancestral village, she said, adding that her great-grandfather was one of the few men on his crew who could read and write. “I’m sure he was helping some of his fellow villagers to be able to send money home.”

Wilson Chow told Stanford interviewers that his great-grandfather, Chow Zun Yok, saved all the money he made working on the railroad in a ceramic pot. “Not paper bills. But the real gold dollars,” Chow said. “He did not send the money back, but, when he returned to China, he carr[ied] all his money.”

New Opportunities Up North

When the Central Pacific was finished, some laborers went back to China. Others stayed, finding work on farms or in larger cities throughout the region. A lot of Chinese workers were recruited to maintain or build other railroad lines.

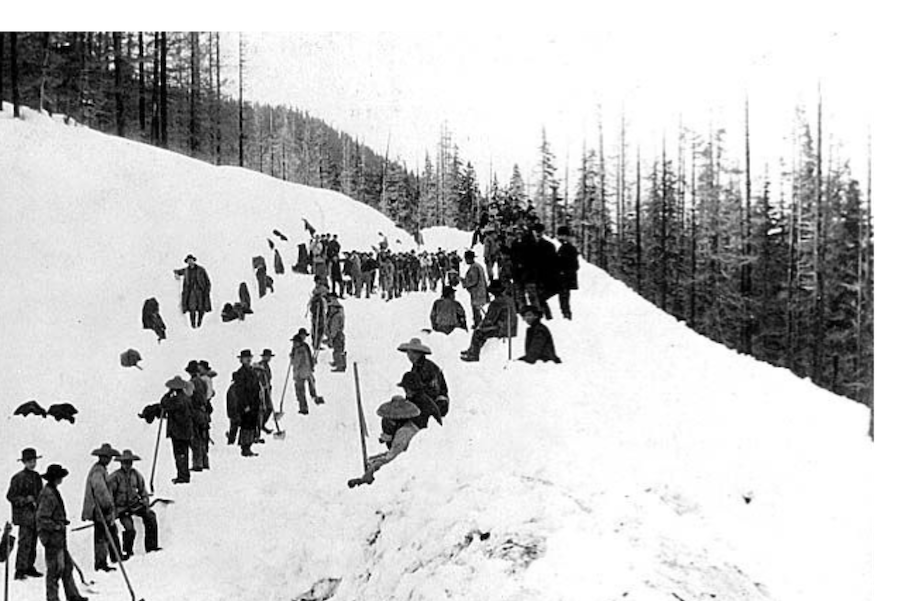

An estimated two-thirds of the workforce on the Northern Pacific Railway were Chinese. They began building the western portion of the railroad in 1878.

“The Chinese were valued workers,” affirmed Dr. Priscilla Wegars, a history professor at the University of Idaho and founder of the school’s Asian American Comparative Collection. “They were steadfast and loyal.”

Wegars said as many as 5,000 Chinese men who ended up working on the Northern Pacific were recruited directly from China by labor contractors like the Six Companies, an umbrella organization run by Chinese merchants in San Francisco that helped immigrants make it to, and find work in, America.

During construction, laborers lived in segregated camps along the railroad, often situated in remote river valleys and mountain vistas. The construction of the transcontinental lines coincided with the illegal seizure of Native American territory. Along the route of what became the Northern Pacific line, Sioux, Northern Cheyenne, Arapaho and Lakota frequently attempted to halt incursions by railroad survey parties and construction crews into their lands—efforts that were ultimately unsuccessful.

Within the camps, said Wegars, the strict separation between the white and Chinese railroad workers did mean, at the very least, that there was less open conflict; the Chinese were largely safe in the camps. “In general, Chinese and whites avoided each other,” said Wegars, adding that the Chinese were able to practice cultural traditions from their native country. For instance, many crews were accompanied by a herbalist.

Lisa See, who writes about the Chinese American experience and took part in Stanford’s archival project, said her great-great-grandfather, Fong See, was hired as a herbalist. “The Chinese laborers had no interest in Western medicine. So it was really helpful to the railroad company to have people there who could treat their Chinese laborers with traditional herbs,” said See.

Historians believe that the Chinese habit of boiling water to make tea kept them from water-borne illnesses like dysentery that impacted many white workers.

Workers insisted on eating Chinese food such as rice, dried vegetables and seafood. To accommodate this need, many railroad crews were accompanied by a Chinese chef, and a network of growers and importers developed throughout the West. Just as they had along the other transcontinental railroads, small Chinatowns sprang up in the railroad hubs along the Northern Pacific line. In these neighborhoods, Chinese merchants opened laundries, restaurants and stores where Chinese workers could find familiar food and other items from home.

Chinatowns, which often abutted white neighborhoods, are also where workers were most in danger of racially motivated violence. According to Bauman, in some Chinatowns—such as those in Pasco, Washington, and Pendleton, Oregon—residents built underground tunnel systems, “partly as a way to stay safe among threats of violence and partly to stay out of the public eye.”

Chinese Railroad Legacy Along the Great American Rail-Trail

To explore the area where Chinese immigrants worked and lived during the construction of the Northern Pacific Railway, visit the aptly named NorPac Trail, which follows the old right-of-way through western Montana and the Idaho Panhandle, crossing Lookout Pass. At the height of the Pass—near the state line—you’ll ride by remnants of trestles and a water tank.

In Mullan, Idaho, the NorPac Trail shares a trailhead with the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes, a 73-mile paved route that passes through areas rich with mining, railroad and Native American history. A portion of this trail between Wallace and Mullan is also along an original part of the Northern Pacific (it was sold to Union Pacific in 1981).

Learn more about the 3,700-mile Great American Rail-Trail.

Finding Community in a Foreign Country

The workers on the Northern Pacific were a “bachelor society”: by and large, married men with families at home. Despite a stark lack of family life in camps and Chinatowns along the railroad, the men were able to establish tight-knit communities that mirrored the ones they had left behind.

For instance, they celebrated holidays together. In Deer Lodge, Montana, a local paper reported that Chinese merchant Gem Kee hosted a Lunar New Year celebration for 700 Chinese residents of the county that included fireworks, food and music.

Other workers banded together to start their own contracting firms, dry-goods stores or produce operations. Owning a business was one of the few paths to upward mobility available to Chinese immigrants.

Community was on display during less happy times, too. “When someone died, others would take care of their belongings, have a ceremony, notify family back home,” Bauman said. Many Chinese also took part in systematic searches for remains along rail lines and near old camps, looking for the bones of their countrymen to collect and ship back to China for proper burial.

Legalizing Discrimination

One year before the final tracks were laid on the Northern Pacific, Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which prohibited unskilled laborers from entering the country and denied citizenship to those who were already here. The law was the culmination of years of anti-Chinese activism on the part of white Americans, who alleged the Chinese drove down wages by accepting low-paying jobs, during which Chinese laborers were terrorized through lynching and Chinatown raids.

According to Wegars, the Exclusion Act forced railroad workers to make a difficult choice: forfeit precious income to return to their families, or stay in America and continue to send money home. She explained that as many Chinese men—now without hope of ever bringing their wives and children to the United States—went back to China, Japanese immigrants began taking jobs on the Northern Pacific and other railroads. “There’s always someone at the bottom of the heap,” Wegars said.

The Exclusion Act had an intended and profound effect on immigration. In 1881, 12,000 Chinese entered the country. In 1887, only 10 did. As the Chinese population in the Pacific Northwest withered, once-vibrant Chinatowns also disappeared, until the only evidence they once existed could be found on old fire insurance maps.

But for the descendants of the railroad workers who stayed, their ancestors’ legacy has remained hidden in plain sight for more than a century.

“If you take a family trip … around in the West, you’ll pass something like China curve, China lake, China bend, China hill—all of these places where there were Chinese who worked there, who made that railroad spur around the corner, who built that bridge over the river. That infrastructure, it’s there because they did it,” See told Stanford interviewers. “We wouldn’t be here today, and enjoying the lives we’re enjoying today, if not for the hard work and the sacrifice and the suffering that came before us.’’

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.