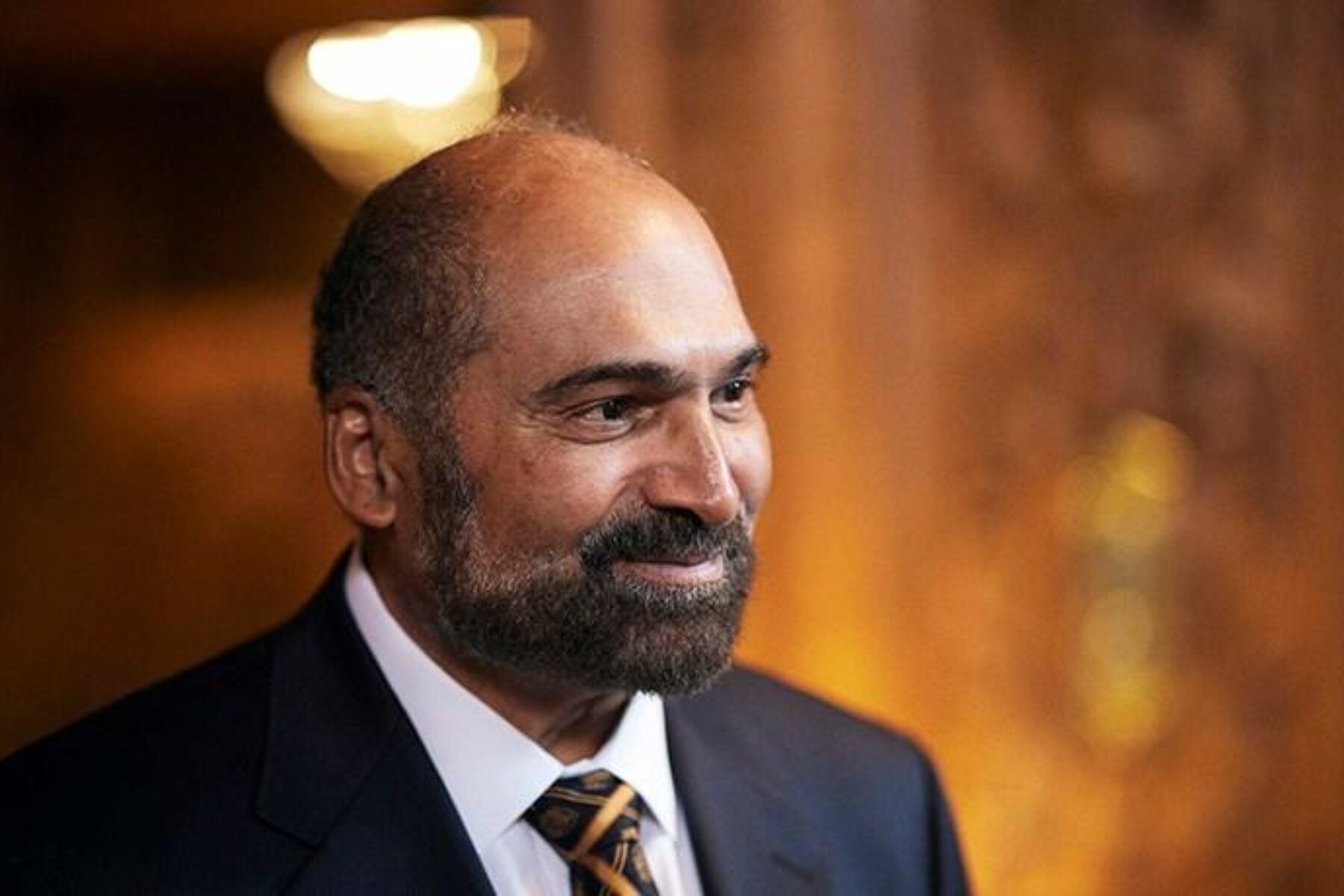

Remembering Franco Harris—Trails and Bicycling Advocate

This article was originally created for the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of Rails to Trails magazine. It has been reposted here in an edited format. Subscribe to read more articles about remarkable rail-trails and trail networks while also supporting our work.

“On a football field, you cannot go much farther than 100 yards. And on a rail-trail, you can go forever.”

—Franco Harris

The Immaculate Reception got its name thanks to the one-in-a-million catch Pittsburgh Steelers Pro Football Hall of Famer Franco Harris made on a last-second heave that ricocheted his way after it bounced off a defender, but it wouldn’t have happened had Harris ever stopped running.

Harris made NFL history on that play in the rookie season of a career that would see him rush for 12,120 yards. And he didn’t stop moving after his retirement in 1984. Harris, who died in December 2022 at the age of 72, became an important advocate for trails and cycling, in particular. And he did so as a member of the Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC) Board of Directors from 1992 to 1997.

“I do remember one thing he said to me [at a board social event],” said RTC co-founder Peter Harnik. “He said: ‘You know on a football field, you cannot go much farther than 100 yards. And on a rail-trail, you can go forever.’ And I just thought that was really, really fun.”

In the early ’90s, Harris owned the Pittsburgh Power, a bike racing team in the now-defunct National Cycle League. He also threw support behind a number of bike-related causes in Western Pennsylvania and beyond. It all made him a natural fit to join the RTC board, several longtime staffers said.

There are several major moments that Tom Sexton, director of RTC’s Northeast Region, can point to as evidence that the rails-to-trails movement had picked up mainstream support in the Keystone State and surrounding region. Former Pennsylvania Gov. Tom Ridge using the term “rails-to-trails” in a budget address was one for sure, he said. Harris’ decision to accept the invitation to join RTC’s board was another. And, like Harris, it was more on the quiet side, Sexton said.

But Harris brought a mainstream name to a cause that Sexton affirmed was, in the early days, considered “a little too-far touchy feely greeny” by some. Harris, the son of an African American World War II veteran and a native Italian, became a legend in a city where the football team’s name honored its blue-collar roots.

Look back in newspaper archives and you’ll find anecdotes about Harris high-fiving runners at the ends of races, encouraging kids to ride with helmets, and riding at the front of the pack to celebrate bike-to-work weeks. Sexton said he would bet that seeing Harris put his support behind trails and trail users must have made things click for a lot of people.

Marianne Wesley Fowler, RTC’s senior strategist for policy advocacy, agreed.

“Well, I think it gave us a kind of cred,” said Fowler, who was serving as the organization’s Southern coordinator when Harris was on the board. “It moved us beyond being perceived as just a sort of warm fuzzy-feeling, do-gooder element of society. It was just sort of a broader support constituency for us. He was a star, you know. He was a star, and he said Rails-to-Trails Conservancy is not only OK—it’s important. That presence of his, that public perception of his involvement, was really important. And then, of course, there was the importance of the role he played internally to the organization, which was also a part of his tenure at RTC.”

Fowler said the public-facing element was big, and she recalled hearing, “Wow, you’ve got Franco Harris on your board?” more than once. “I mean, even I know about the Immaculate Reception,” she said.

“He makes a great cheerleader for cycling.”

—1995 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette column noting why Pittsburgh should be called the “best bicycling city in America”

Ken Bryan, senior strategist for external relations and Florida director, said Harris’ name was among a collection that he would drop to help connect the dots for people that the rail-trail movement had steam behind it. Bob Naegele, then-owner of Rollerblade; Richard Burke, then-Trek CEO; Richard Schwinn; and Franco Harris—they all helped move the needle, Bryan said.

Take a look back in the early ’90s, when there wasn’t as much consensus on funding for rail-trail projects as you’ll find today, and you will see that Harris’ support mattered. A 1993 York Daily Record editorial in support of the Keystone Bond Fund referendum noted that the Pennsylvania Landowners’ Association had opposed the ballot measure, which would benefit—among other public facilities—parks, museums, state forests and “rails-to-trails.” (It was still in quotes back then.)

“But just about everyone else, from Franco Harris to park rangers to librarians, is pushing for the passage,” the Pennsylvania paper’s editorial noted. Two-thirds of the state’s voters supported it.

His advocacy was pointed to in a 1995 Pittsburgh Post-Gazette column noting reasons that justified an effort to call Pittsburgh the “best bicycling city in America,” and stating that “he makes a great cheerleader for cycling.”

Harris’ advocacy efforts came on the heels of his purchase of the Pittsburgh Power. Todd Koltes, general manager of the Power, told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 1991 that Harris was quickly drawn to the sport.

“It’s something to see—10, 12 guys coming out of the turn at nearly 40 mph,” Koltes said. “It took Franco by surprise. He never saw a bike race in his life, and he just loved it—the speed and the power. So, if we can convert Franco, we can convert anybody.”

Harris was drawn not only to the sport, but also to the development of a new league that would showcase it.

“Whenever you do something new, you ruffle some feathers with the establishment,” Harris told the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette in 1991. “Well, I guess I’ve always liked to do that.”

As an RTC board member, Fowler recalled, Harris was a thoughtful supporter who listened to other points of view first before pushing the organization to take big steps based on what he’d learned.

“I was always impressed at how cerebral he was actually,” Fowler said. “Thoughtful and cerebral, and he never backed down from—or thought the organization should back down from—a bold next step or a bold initiative. I mean, he really had that ‘Go for it’ [energy]. But it wasn’t like a pep rally ‘Go for it!’ It was, ‘Here are the well-thought-out reasons why this is the right direction for the organization.’”

When he supported something, he showed up for it, too. In October of 1992, a Sports Illustrated article on the rails-to-trails movement began by asking what in the world Franco Harris was doing on an abandoned rail-trail in Western Pennsylvania with a bunch of cyclists.

“Hey, I think it’s a great idea,” Harris was quoted as saying. “I’m a big believer in cities having a place for people to go to ride their bikes, and when I heard about this, I said I’d be there.”

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.