A Celebration of Completion for Vermont’s Lamoille Valley Rail Trail

After more than two decades of effort and an infusion of cash from the state legislature in 2020, Vermont’s Lamoille Valley Rail Trail (LVRT) is finally complete. The state’s $2.8 million in funding, matched by $11.3 million in federal dollars, was championed by Governor Phil Scott and brought the 93-mile route a long way from the days “collecting pennies from the jug at the gas station with the sign for LVRT donations,” reflected Doug Morton, a senior transportation planner with Northeastern Vermont Development Association.

Now stretching from St. Johnsbury, near the New Hampshire state line, to Swanton, near the borders of New York and Canada, it’s become the longest rail-trail in New England. Its jubilant grand opening took place on Sat., July 15, with Gov. Scott joining the celebrants and biking the trail from end to end.

Over the years, countless volunteers have kept the vision of the state-spanning, all-season trail alive, especially VAST—the Vermont Association of Snow Travelers—who began leasing the corridor from the state in the early 2000s and opened as many sections as they could with limited funding, performing continual maintenance to keep the pathway usable for the public. An early boost for the project came in 2005 with $5.2 million in federal funding obtained by U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.).

“The whole thing is really amazing,” enthused Morton. “It’s a great example of community-supported, state-funded infrastructure. It really is a success and I applaud the State of Vermont. They pulled off an incredible feat in completing this.”

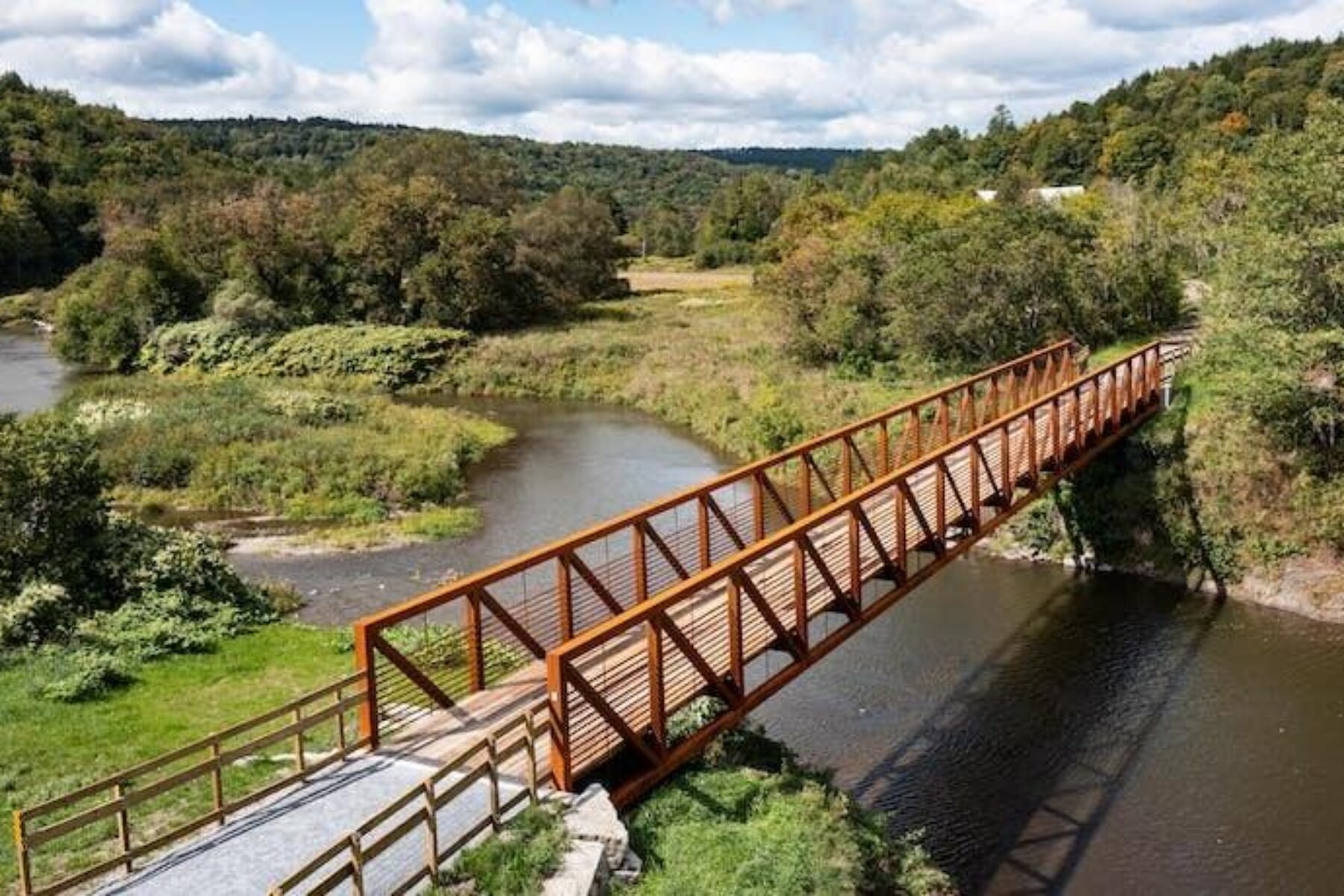

The rail-trail’s last piece—covering 6 miles between Wolcott and Hardwick, including the historical Fisher Covered Bridge, one of more than 50 bridges along the entire trail—was finished in 2023. During the final push toward completion, management of the trail moved under the Vermont Agency of Transportation (VTrans).

“I think the trail will have a positive substantial impact for all of the towns that it goes through,” said Jackie Cassino, the rail-trail program manager for VTrans. “It can really capitalize on the Vermont brand of these small New England villages and downtowns, and also provides a rural setting from the working lands, dairy farms and hay fields on its western half to the wooded feeling and the sugar operations for maple syrup on its eastern side. It has all of that, which is appealing to a lot of different kinds of people wanting to have that Vermont experience.”

Related: Trail of the Month: Vermont’s Lamoille Valley Rail Trail (May 2018)

The Key to Success

Morton says the project’s secret sauce has been “collaboration, collaboration, collaboration.” As a state with the second lowest population in the country, working together to get things done is deeply rooted in the ethos of Vermonters. Touching five counties and connecting 18 communities, the development of the LVRT required a tremendous amount of coordination and cooperation between local and state government entities, three regional planning commissions and numerous volunteer groups.

“We’ve had so many different user groups interested from the very beginning,” explained Morton. “I think by necessity we’re forced to find partners. We don’t have a lot of money and we don’t have a lot of people, but we do have a lot of enthusiasm and people that that are willing to participate.”

The firm crushed-stone pathway is ADA compliant and supports a myriad of uses in the warmer months—walking, running, cycling and horseback riding—as well as snowmobiling, snowshoeing, cross-country skiing and dogsledding in the winter.

“The snowmobile community and the other trail communities really get along,” said Tom Sexton, the Northeast regional director for Rails-to-Trails Conservancy. “They just wave and they know that they have to share; there’s a high degree of etiquette and cooperation between all the users in Vermont.”

This collaborative spirit is displayed in towns such as Wolcott, where residents motivated by the rail-trail coming through town and the anticipated influx of visitors with it have banded together in committees to work on community-enhancement projects. Sitting near the center of the LVRT, Wolcott is a homespun place with “just a little general store,” according to Linda Martin, the town’s selectboard chair. She ticks off a handful of projects completed in just the last few years, including a trail kiosk and parking area with grills and picnic tables, the conversion of an old railroad depot into a library and the creation of a community garden.

And even more is coming. A vacant schoolhouse (circa the 1800s) is hoped to be refurbished into a café and historical museum; a 700-acre town forest with mountain biking trails is in the works; a wastewater facility may be built to add restroom amenities; and a spur between the rail-trail and the elementary school is planned. For a town of only about 1,700, such progress seems remarkable.

“I think the rail-trail has really brought positive feelings to the community and a reason to get some things done,” said Martin, adding that the rail corridor used to be overgrown and “kind of spooky” but is now enjoyed by “tons of people of all ages.”

Bringing the Cheddar to Vermont

This investment in money and effort is expected to pay off with the LVRT having the potential to generate $4.7 million in sales activity annually now that it’s completed, according to a 2022 study analyzing 38 miles of the trail between St. Johnsbury and Hardwick.

“That’s the real power of an asset like this,” noted Drew Pollak-Bruce, a senior recreation planner with SE Group, which developed the economic impact study. “In suburban Chicago, a rail-trail is not going to make the difference in any sandwich shop, but in these small towns in Vermont, the trail can help keep a place open—like, those 10 extra sandwiches on a Saturday really do make a difference.”

A Burlington resident, Pollak-Bruce rode the LVRT with his dad for the first time this past May, enjoying the trailside businesses firsthand, especially Morrisville’s Lost Nation Brewing, a popular stop almost guaranteed to be mentioned by any local you talk to about the trail. He stressed that these quality-of-life assets—new community amenities and attractions, stronger businesses and the trail itself—are critical not just for drawing tourists, but also for attracting more people to live and work in the region.

Trail advocates are already looking at ways to maximize the trail’s benefits, such as the development of trip-planning resources (including a new Vermont Rail Trail System website) and a trail-friendly business program, and supporting the towns in their quests to add amenities, parking and short connectors into city centers to lure trail users to local businesses.

“A trail like the LVRT has the potential to have such an economic impact on smaller towns,” said Cassino. “In Vermont, where recreational tourism is a huge part of our economy, the fact that this is a multimodal, accessible trail that is open to anyone has a special place in that.”

Related: Rural Revitalization: Vermont’s Lamoille Valley Rail Trail (Rails to Trails, Spring/Summer 2022)

A Framework for the Future

These economic impacts can ripple farther outward through linkages with other trails, such as the 27-mile Missisquoi Valley Rail Trail, which crosses the western end of the LVRT in Sheldon and ends just shy of Québec. Near the LVRT’s eastern end, the town of Cabot—situated between the rail-trail and the Cross Vermont Trail—is working on project to connect the two via the Bayley-Hazen Military Road, a backcountry experience on an old Revolutionary War route.

Although in the very early stages of discussion, the development of a 22-mile route called the Twin State Rail-Trail between St. Johnsbury, at the southern tip of the LVRT, and Whitefield, just over the border in New Hampshire, has also been proposed. More broadly, the LVRT is a key part of the expansive New England Rail-Trail Network, which aims to unite the region’s six states—Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont—by multipurpose trails.

Cassino considers this looking outward at other connectivity opportunities the “natural next step” in the LVRT’s evolution. “My plan is that, as the agency continues to invest in the rail-trail program and sets up these systems that are sustainable—both from the trail maintenance and operations perspective, but also how we engage with the local towns—that, when those opportunities become available, we can easily dial into it, whether it’s connecting across Canada or to New Hampshire or to New York.”

Sexton, who has been spearheading the regional network, sees the LVRT as a role model for all these other trail efforts. “It’s important physically because it’s going to connect other vital parts of the trail system, but it also teaches us the importance of leadership to complete major projects like this.”

Related: Top 10 Trails in Vermont

The New England Rail-Trail Network is a project Rails-to-Trails Conservancy is working on with trail advocates and transportation leaders from six states—Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island and Vermont—to advance a plan for connecting the region’s 1000 miles of open trail, and develop criteria for prioritizing future trail projects that can build momentum and mobilize support for the effort.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.