Awaiting Takeoff: The Wright Brothers’ Biking Legacy

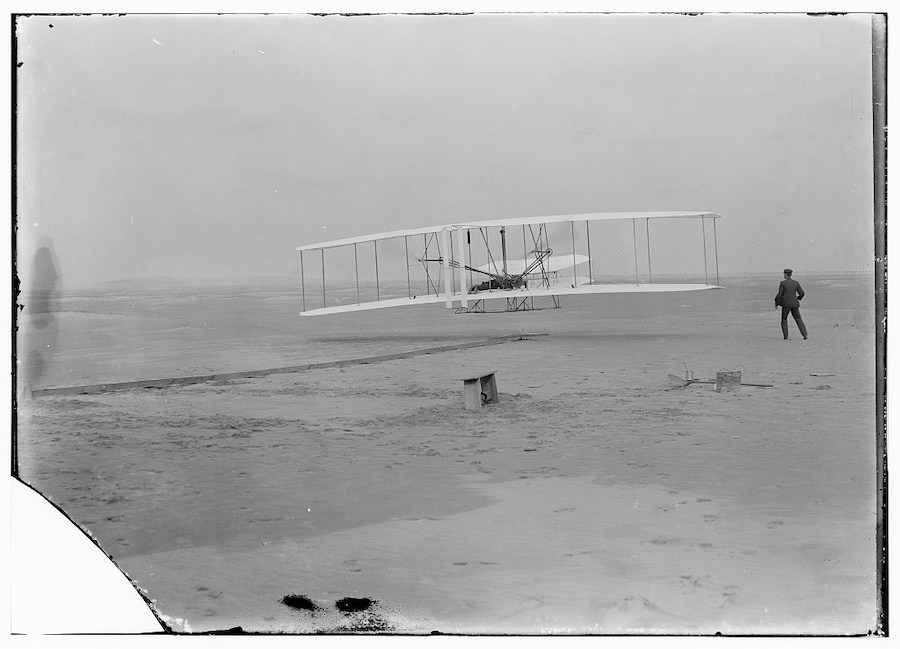

On a gray North Carolina beach, 120 years ago this December, Orville Wright completed the first powered flight of a heavier-than-air aircraft as his brother Wilbur looked on. The 12 seconds that the Wright Flyer—which the brothers designed and built back home in Dayton, Ohio—spent airborne would earn the inventors an enduring place in both the history books and the American imagination.

And so, chances are very good that you’ve heard that story. You’ve probably seen the black-and-white pictures of the two men in suits, their deceptively simple glider floating low over the barren landscape. What you may not know is that, before they taught the world to fly, the Wright brothers helped it get up on two wheels, assembling and selling bicycles to a society gone wild for the first practical and affordable form of personal mechanical transportation.

More than just a job on their road to fame, the brothers’ time building bikes helped them better define and solve the problems of powered flight—and even shaped how they constructed the glider they flew on the beach that day.

A Curious Childhood

Born in 1867 and 1871 respectively, Wilbur and Orville were two of Milton and Susan Wright’s seven children. A bishop in the United Brethren Church, Milton traveled often for church business but almost always returned home with a gift, something to expose the children to the wider world and encourage their curiosity. Once, he came back from a work trip with a rubber-band-powered helicopter, which Wilbur and Orville immediately tried to replicate. Milton also urged the boys to write letters while he was away and spend time with the books in the family’s large library.

In 1889, after their mother died of tuberculosis, Orville dropped out of high school to open his own print shop, and Wilbur, who had delayed college to care for his ailing mother, became his business partner. The two men started a handful of newspapers, but ultimately couldn’t compete with the larger, more established papers of the day. The Wright brothers began looking around for other ways to satisfy their curiosity—and pay the bills.

“They were always interested in a lot of things, and they were autodidactic,” said Nick Engler, director of the Wright Brothers Aeroplane Company, an organization that hosts a virtual museum about the Wright brothers and builds replications of their inventions. At the end of the 19th century, the recently invented “safety bicycle” was all the rage. With two wheels of equal size, the safety bicycle was easy to mount and steer, making it the first accessible and affordable form of individual transportation. In 1892, to supplement income from the printing business, the duo began repairing and selling bicycles. By 1896, they were building their own.

Exploring Dayton

Dayton, Ohio, is full of aviation heritage, much of it accessible by trail. The Wright Cycle Exchange is only a couple short blocks from the Wolf Creek Trail. Next door, at the Wright-Dunbar Interpretive Center, visitors can explore exhibits and displays related to the city’s most famous brothers as well as aviation history and information on influential Black poet and journalist Paul Laurence Dunbar, a Dayton native.

Heading east, the Wolf Creek Trail dead-ends into the Great Miami River Trail. About 3 miles south of that junction, trail-goers will find Carillon Historical Park, which houses the world’s largest collection of Wright brothers-related artifacts from both their bicycle and airplane days. “A cycling enthusiast might get just as much out of it as an aviation enthusiast,” said Brady Kress, president and CEO of Dayton History.

The Wright Cycle Company

The brothers unveiled their first model in 1896, a top-of the-line bike they called the Van Cleve, named after their great-great-grandmother, Catharine Benham Van Cleve Thompson, one of Dayton’s first settlers. They marketed their new bike with the slogan: “Van Cleves get there first.” Their second model was a more affordable bike they called the St. Clair (a reference to Arthur St. Clair, the first governor of the Northwest Territory, which included Ohio).

According to Engler, what the Wrights did in their bicycle shop “wasn’t manufacturing as we think of it. It was boutique manufacturing. They would buy the individual parts from different suppliers, put them together and put their own head badge on them.”

This meant that the Wright brothers sourced materials themselves—including saddles, pedals, frames and even the head badges (brand name plates)—from other companies based on how they wanted their bikes to look (and cost). The men did add a few original components, including coaster brakes and a wheel hub they were especially proud of for keeping out dirt and keeping in lubrication.

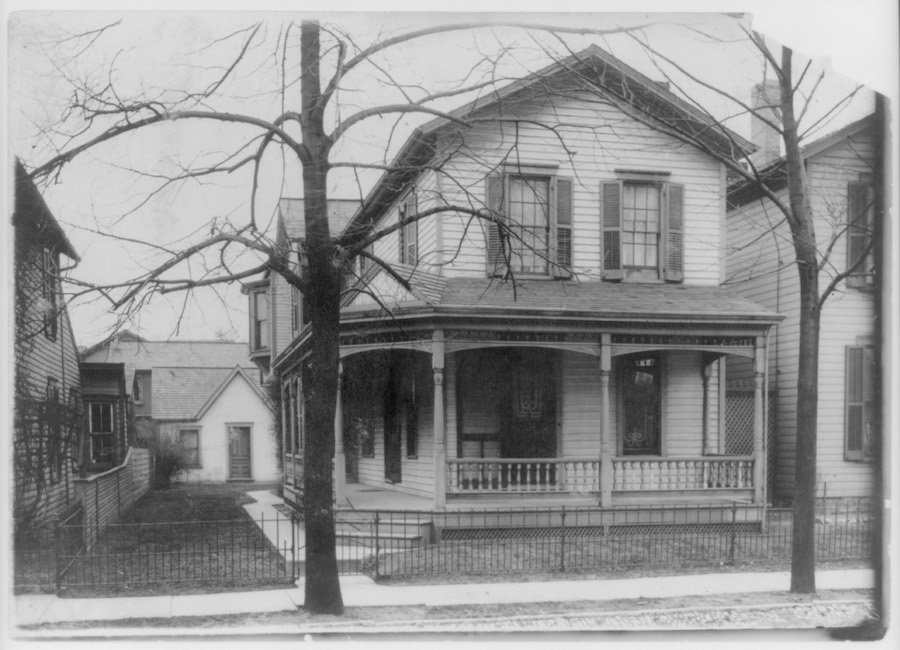

The Wright Cycle Exchange, later renamed the Wright Cycle Company, occupied a storefront on Dayton’s busy west side. Engler said that if you were to walk into the shop in the middle of the afternoon, you’d likely find it unoccupied: “The brothers would be in the back building bicycles.” Customers who came to pay a bill could do so by placing money in an unlocked box Wilbur and Orville kept on the counter.

For a time, the bicycle business was good to the Wright brothers, who earned approximately $3,000 in 1897 (more than $100,000 in today’s dollars) and were able to amass a nest egg that would eventually go toward building their fliers. But the prosperity was not to last.

As big manufacturers bought out small ones, the prices of bicycles began to plummet. “The Sears and Roebuck’s 1898 catalog listed a bicycle for $8.98,” said Engler. “The Wright brothers couldn’t compete with that. So they started looking around for something else to do.”

From Wheels to Wings

That something else, as we know now, was airplanes. But even as the Wrights began devising how to master controlled flight, bicycles were never far from their minds.

“Wilbur and Orville grasped the central problem of creating a machine that would fly in a way that previous inventors had not,” said James Tobin, author of “To Conquer the Air: The Wright Brothers and the Great Race for Flight.” Some inventors thought the problem was power, but Wilbur believed it was balance—especially balancing an aircraft in the wind. “The bicycle is also a problem of balance. Wilbur had thought a lot about the physics of riding a bicycle, and that helped him as he approached the flying problem.”

Bicycle parts also found their way into the Wrights’ designs. The 1903 flyer that Orville flew in North Carolina was full of spoke wires and bicycle chains. “If you look at it from the side, you can see there are two bicycle frames holding the propellers,” said Engler.

“Only bicycle manufacturers would build a plane like that,” said Brady Kress, president and CEO of Dayton History. “They’re riddled with all the things a bicycle shop would have laying around.”

Kress’ organization oversees Carillon Historical Park, a 65-acre open-air museum where visitors can admire the 1905 Wright Flyer III, the only airplane designated a National Historic Landmark. Next door stands the Wright Bicycle Shop, a replica of how the Wright brothers’ store would have appeared in late 1901—when they were building both bikes and fliers. Carillon Historical Park is also home to two of the only five remaining Wright bicycles in the world.

At the nearby Wright Cycle Exchange, managed by the Dayton Aviation Heritage National Historical Park, visitors can tour the building where the brothers operated their business from 1895 to 1897.

Related: 10 Great Places of Learning Along the Great American Rail-Trail

Katharine, the Unsung Sibling

While Wilbur and Orville are household names, one influential Wright sibling that historians sometimes neglect is their sister, Katharine. The youngest of seven children and the only surviving daughter, Katharine became the family’s primary caretaker at 15 when her mother passed away and later an influential businesswoman and Wright Company leader in her own right.

The brothers wrote many letters to Katharine from the windswept beaches of Kitty Hawk, where they spent winters testing their gliders. From afar, their sister provided support and encouragement, while lamenting that the most exciting part of her day was going out to buy groceries, according to James Tobin, author of “To Conquer the Air: The Wright Brothers and the Great Race for Flight.”

“She was very much the woman of the household, fulfilling the traditional female role,” he said.

But Katharine harbored ambitions that would take her far from the domestic sphere. In 1898, she became the only Wright sibling to graduate from college. She worked as a high school English teacher until 1908, when she quit her job to care for Orville after an accident left the inventor with a bundle of broken bones. The following year, she accompanied him to Europe, where Wilbur was demonstrating the brothers’ flying machine and fundraising to build more fliers.

In Europe, Katharine shined, becoming a spokesperson for the notoriously shy brothers as they were feted by kings and dignitaries. “Katharine was sort of their ambassador, and she just took to that role,” Tobin explained. “She was much more sociable than her brothers. She was warm, she was funny, she was gracious.” Before they returned to the United States, all three siblings were awarded France’s Legion of Honor, the country’s most prestigious award.

When Wilbur died in 1912, Katharine became an officer of the Wright Company and moved in with Orville, closely managing his correspondence, business dealings and social schedule. She also made time for her own projects, lobbying for women’s suffrage and serving as one of the first female trustees of her alma mater, Oberlin College. Katharine died in 1929, having enjoyed a colorful and expansive life, despite society’s restrictive expectations of women in the early 20th century. “Who knows what she could have been if she lived in a different era,” said Tobin.

This article was originally developed for the Fall 2023 issue of Rails to Trails magazine. It has been reposted here in an edited format. Subscribe to read more articles about remarkable rail-trails and trail networks while also supporting our work. Have comments on this article?

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.