A Path Toward Healing

Negotiations with the 130 Northern Cheyenne imprisoned at Fort Robinson during the winter of 1879 were as simple as they were brutal: Voluntarily depart for the so-called Indian Territory that had been set aside for them in Oklahoma or else.

Or else we’ll cut off your food, or else we’ll withhold water, or else there will be no more fuel for your fire.

The commander of Fort Robinson in the northwestern corner of Nebraska, where the Northern Cheyenne were being held captive in a converted calvary barracks, had made good on every single or else. It had been more than five days since his prisoners had eaten. Wood was no longer being delivered for their heating stove, and they were slowly freezing in their makeshift prison. Reduced to scraping frost from windowpanes for precious drops of water, the Northern Cheyenne knew they were doomed regardless of their choice: a slow death in the icy barracks, or a brave and honorable death outside in their homeland.

As night fell, the starving prisoners reassembled their few rifles from components they’d scattered and hidden. They took aim at the fort’s guards and prepared to fight for their lives. The Northern Cheyenne’s journey home had begun.

Escape from Indian Territory

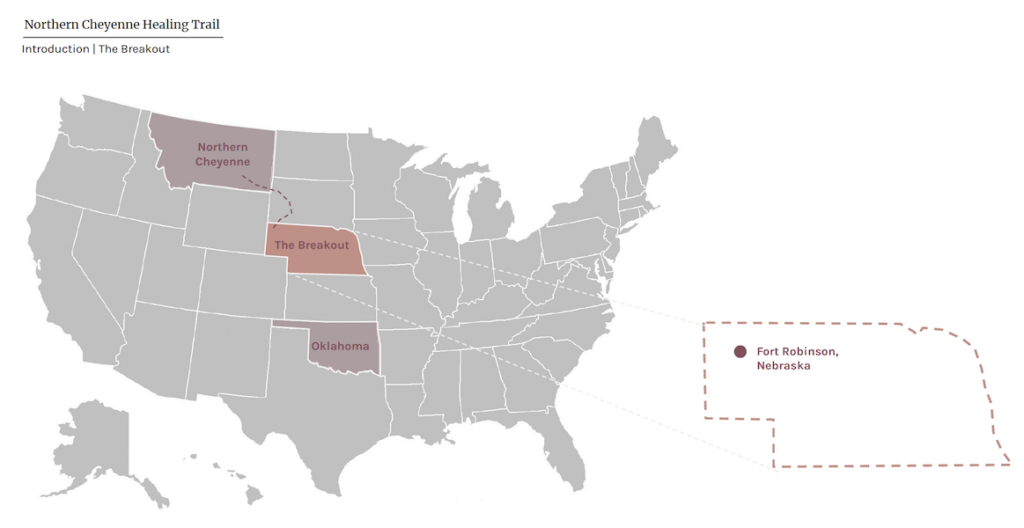

But this story, says Gerry Robinson, truly begins more than a decade earlier with the Treaty of Fort Laramie. A historian, author and Northern Cheyenne himself, Robinson called it “the last legitimate treaty between the Northern Cheyenne and the U.S. government.” Ever since, he explained, there had been an effort to get them to move on to Indian Territory, hundreds of miles from their traditional homeland in the northern plains near the Black Hills.

Robinson—no relation to the namesake of the fort his ancestors escaped from—explained that the Northern Cheyenne had made a good faith effort to live on the Oklahoma land to which they’d been relocated. “‘Give it a year,’ they were told, and if they didn’t like it, they could come back” to their ancestral home, recounted Robinson. “That was a lie.”

Living in close quarters with other relocated tribes, the Northern Cheyenne were exposed to measles and malaria—highly infectious diseases to which the Natives had no natural defenses. “They lost over 50 of their number in a year,” said Robinson. “Usually the weaker ones—the children and the elderly—but a fair amount of healthy adults as well.” With too little food and too few resources, the Northern Cheyenne attempted a bison hunt but found the animals had been all but wiped out in a concerted and government-sanctioned effort by white settlers. “It was a disaster,” said Robinson. “They had to eat their horses just to survive the hunt.”

Within six months of arriving in Indian Territory, tribal elders informed the government agent in charge of their relocation that they would stay true to their commitment, but would return north as soon as their agreed-upon year was up.

While the Northern Cheyenne honored their word, the U.S. government did not; reneging on its agreement, the government denied the request to return peacefully. Under cover of night, 353 Northern Cheyenne slipped away in September 1878 and started a perilous trek back home.

Pursued relentlessly by the U.S. Army, they made their way steadily north and westward. For a month and a half, the group had evaded capture, but their numbers had been reduced in several pitched battles, and the young, injured and elderly had trouble keeping up with the demanding pace. Shortly after fording the South Platte River east of Ogallala, Nebraska, the refugees decided to split up. A swifter, healthier force continued onward under the leadership of Chief Little Wolf to winter in the Nebraska Sand Hills and eventually the Yellowstone region of Montana Territory; those less able to keep the pace followed Chief Morning Star.

“Morning Star was in his 60s by then,” said Robinson. “At that point, he’d lost a son at [the battle of] Little Bighorn, two sons and a son-in-law at [the battle of] Red Fork, and then his wife” during the flight from Indian Territory. “He’d lost five of his family and he was tired,” Robinson explained. “He was what’s called an old-man chief, and the responsibility of an old-man chief is to take care of the women and children.” The injured, the young, the sick and exhausted—“they needed to get off the trail.”

The group decided to seek refuge under the Lakota chief named Red Cloud on the agency—a forerunner to a Native reservation—that his people had retained in an 1868 treaty with the United States and was named for him. Morning Star and Red Cloud were related by marriage (see sidebar), and “The plan was to go in among the Lakota people and blend in,” explained Robinson, “and after maybe a year when everyone was healthy again, possibly move north and rejoin Little Wolf.” What Morning Star didn’t know was that in the year they had been gone, the Red Cloud Agency had been moved by the U.S. government 60 miles northward, and Morning Star’s group was instead heading straight toward Fort Robinson, an Army stronghold.

And so it was that Chief Morning Star’s band found themselves in blizzard conditions and surrounded by soldiers from the nearby fort. Before surrendering themselves, the group disassembled the guns in their possession and scattered the pieces and ammunition among their members—hidden under clothes and camouflaged as jewelry.

Morning Star or Dull Knife?

History generally remembers Chief Morning Star as Dull Knife; even the college on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation honoring him is so named. But Gerry Robinson, author, historian and tribal member, notes that the revered chief “married into the Lakota tribe, and his brothers-in-law gave him the name Dull Knife in a joking way.” It was good-natured ribbing that stuck, but Morning Star, or Vóóhéhéve in his native tongue, “is his Cheyenne name.”

The Breakout

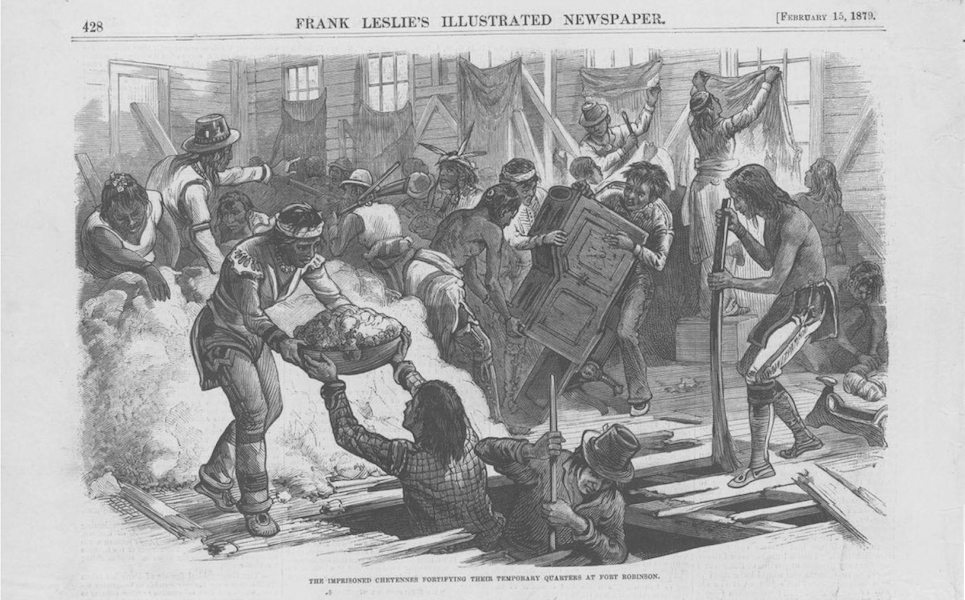

The captured Northern Cheyenne were put in an unused barracks on the grounds of Fort Robinson—130 people squeezed into a space only a little larger than an average elementary school classroom today. Although one pistol had been discovered by the soldiers, some rifle parts were successfully smuggled in and cached away under the floorboards of their communal cell.

Captain Henry Wessells, Jr., the recently appointed commanding officer at Fort Robinson, at first employed a soft approach in his attempts to convince Morning Star to voluntarily lead his people back to Indian Territory. “Initially they were treated well,” said the historian Robinson. “They were still poorly clothed, but they were fed well and allowed out for hunting” during the day with the stipulation that everyone return and be accounted for each night. But as pressure mounted from the commander’s superiors, so too did his pressure on the Northern Cheyenne.

The fort commander eventually received orders to send the Northern Cheyenne back to Indian Territory. “After failing to get them to agree to go south, he realized he was getting nowhere by trying to talk to them,” said Robinson. “He had the doors and windows barred. He cut off their food. There was a stove in the barracks for warmth, but he stopped delivering wood. They were like that for three days and still would not agree to go. So he cut off their water as well.”

After five full days of this treatment and seeing no other alternative, Robinson recounted, the group waited until nightfall. “They opened up the floorboards, reassembled and loaded their weapons, and devised an escape plan.” After firing simultaneously on three patrolling guards, they broke through a window and poured out into the night.

Between the Barracks and the Buttes

Camp records from that day show it was 10 degrees around the time of the breakout. With a full moon reflecting dazzlingly off six inches of white snow, it was like running out “into bitter cold daylight,” said Robinson. The escapees followed the frozen-over White River upstream toward nearby buttes, many stopping to break through the ice, desperate for water, as cavalry soldiers “swept down the river, just firing indiscriminately, killing anything that moved.”

Following the escape plan they’d devised, several armed Northern Cheyenne fell to the rear in a desperate attempt to hold back the pursuing force.

The Northern Cheyenne “were familiar with those buttes,” said Robinson. “There is a passageway that you can’t see from the ground, but they knew where it was and made their way up. Barely clothed, in winter, in the middle of the night, they climbed.” The group ascended some 300 feet from the river below, the sounds of the firefight dwindling behind them.

Those that provided the rearguard force to protect the escapees were among the many lost that night. “Twenty-six Northern Cheyenne were killed between the barracks and the buttes,” said Robinson. “Nearly half of them women and children.” Another 50 were recaptured.

More than 30 Northern Cheyenne eluded soldiers for the next two weeks in a display of what Robinson called “resiliency and ingenuity.” On foot with only the provisions that some managed to take while fleeing, they had made their way overland some 40 miles northwest of Fort Robinson. Several died along the way before the final 32 made their final stand in a buffalo wallow. Exhausted, outnumbered and pinned down by four companies of soldiers and cannon fire, “that was it, that was the end. Eighteen men, five women and three children died from that final brutal attack.”

Refuge at Last

Morning Star himself was not among those massacred at what became known as “The Pit.” He and six others had gotten separated from the main group during the escape from Fort Robinson and again made for Red Cloud’s people. They eventually found themselves at the homestead of Jessie and Gus Craven, a Lakota woman and white settler that Morning Star knew. Escaping detection by traveling at night and subsisting largely on wild rose hips—the seed pods of rose plants—Morning Star led this much smaller band nearly 50 miles in the dead of winter. “Gus then took the group to Bill Rowland, my great-great-grandfather,” said Robinson. Rowland lived at the Pine Ridge Reservation, the place to which Red Cloud had been relocated.

After all their tribulations—forced relocation to Indian Territory, an overland trek back to their homeland while being picked off by pursuing soldiers, imprisonment, starvation, an escape from the fort and the loss of so many of their tribe—Morning Star and a small handful of his family had found refuge at last.

Local newspapers generally painted Natives “as red savages and bloodthirsty renegades,” said Robinson, “but papers in the East were much more sympathetic to the Northern Cheyenne’s plight. Many reporters and columnists understood that the Cheyenne were being mistreated and were dying down in Oklahoma—and so their desire to go back home was well understood.”

Those sympathies eventually helped drive a change of heart—and change of policy—in regard to the Northern Cheyenne: “Essentially,” said Robinson, “that’s how we came to be allowed to live in our homeland once more.”

Our Monument; Our Story

The events of Fort Robinson, while seminal in the Northern Cheyenne’s quest for freedom and autonomy, were not necessarily a well-known part of their history in the modern era, even among tribal members, said Major Robinson, the younger brother of author and historian Gerry Robinson. Major Robinson explained that he himself learned about the fort quite by accident: Returning from a road trip out East years ago, “I was driving back toward the reservation. I was in Nebraska, and I saw a sign for this place called Fort Robinson,” he recalled. Thinking it interesting that he shared a name with the fort, he decided to visit.

As he learned what had happened there, “I was shocked,” said Major Robinson. “I had never heard of this [breakout event]—it was just not talked about the entire time that I grew up on the reservation. It wasn’t included in any history books … and I was devastated.”

Vincent Whitecrane likewise shared that while the events of Fort Robinson were certainly known to some, they weren’t widely memorialized among his people. He recalled a long-ago phone call from the secretary of the tribe asking if he’d be willing to drive tribal elders some 350 miles to Fort Robinson for a first-of-its-kind powwow ceremony. “One of them was my mom, and she’d never been down there,” said Whitecrane, “and I only went to Fort Robinson once before that.”

Now a tribal elder himself, Whitecrane noted that all that existed at Fort Robinson as a testament to what the Northern Cheyenne had endured was a single wooden sign. Riddled with both inaccuracies and bullet holes, the sign “didn’t come from an Indian perspective,” said Major Robinson. “It certainly didn’t come from a Cheyenne perspective.”

“The elders were really emotional,” Whitecrane recalled. “Our people weren’t being honored.” That 2001 visit proved to be a pivotal point in the tribe’s collective approach to honoring those who died in the breakout and subsequent pursuit. “We decided then we wanted to build a monument here,” said Whitecrane. “Our monument. Our story. Our point of view.”

With a degree in architecture and a personal desire to help tell his people’s story, Major Robinson was asked to lead the initiative and readily accepted. “Our ancestors fought; many of them didn’t survive, but they gave their lives so that we would have a home” he said. “I want to be a part of remembering; I want to be a part of telling the story and healing from it as well.”

The land on which the monument would sit had already been donated to the tribe, so Major Robinson could hardly have expected the years of fundraising, design and logistical challenges that would follow.

The stone and steel monument was halfway completed when funding ran out, explained Dave Sands, the executive director of the Nebraska Land Trust. At a meeting with Northern Cheyenne representatives, Sands learned of the predicament and stepped up “kind of on the spur of the moment—literally, without giving it much thought,” he said. “I pledged that the Land Trust would help them to raise the funds needed to complete the monument.”

“I’m not a person that wants to make promises I can’t keep” continued Sands, but he was confident that Nebraskans would support this effort to preserve Native history. He set to work on fundraising, little knowing how successful his very first attempt would be. Over lunch with Julie Schroeder, a longtime supporter of the Land Trust, he mentioned the Northern Cheyenne monument he had recently promised to raise funds for. “She got a very strange look and immediately said, ‘Dave, that’s something I need to support.’”

Astounded at her offer of a $25,000 donation, Sands said, “I picked my jaw up off the table and asked why she felt compelled to donate to the project. ‘My grandfather was the commander of Fort Robinson when the breakout occurred’ she told me. What are the chances of that? It just kind of blew me away.”

With this generous first donation secured, Sands said it gave him hope that he could make good on his promise of the Land Trust’s help. “It sent a message that this thing is going to work. I think we’re going to pull this together,” he said.

Some 15 years after the project originally began, the monument was funded, completed and unveiled in 2016. “I didn’t think it would take that long,” said Major Robinson. “But it took as long as it needed to take.”

Situated west of Fort Robinson State Park near the base of the buttes that the Northern Cheyenne escaping the fort fled to, the red pipestone and black granite monument pays tribute to those who perished in the escape. Each of its four sides—four being a sacred number among the Northern Cheyenne that represents the cardinal directions—bears a bronze plaque that tells the story of the breakout through the words of survivors who were there. And capping it all is a gleaming stainless steel morning star, the four-sided symbol of the tribe that’s featured on its flag.

Historical accounts have referred to the events at Fort Robinson by various names: Cheyenne Outbreak, Fort Robinson Massacre, the Northern Cheyenne Massacre and more. Each name carries with it unspoken assumptions, noted Gerry Robinson. An outbreak sounds like the Natives were a virulent problem; referring to it by the name of the fort frames everything around the dominant culture’s perspective; calling it a massacre—while wholly accurate—skims over much of the historical context of what happened.

Until recently, the term generally preferred was the Northern Cheyenne Breakout, but just as the monument represents a better understanding of the events, so too does what it’s called. The Northern Cheyenne’s Tribal Council voted recently to change the name of their group focused on these events to the Northern Cheyenne Journey Home Committee. “It is a more accurate reflection of our ancestors’ decision that day,” said Major Robinson, “which wasn’t just to break out; it was to journey home, or die fighting to get there.”

Shortly after the monument was dedicated, Edna Seminole, one of the tribal elders who had helped set the project in motion, passed away. “But before she passed,” recalled Major Robinson, “she said ‘the next project we need to do is a trail.’”

Northern Cheyenne Healing Trail

Once completed in 2025, the Northern Cheyenne Healing Trail will be part of the country-spanning Great American Rail-Trail®. While the 4-mile segment will be only a small portion of the overall route, it will have an outsized emotional impact. Telling the tale of the Northern Cheyenne’s escape from Fort Robinson, it will offer shaded arbors with seating at four points along the trail to encourage travelers to rest and reflect on the traditional Cheyenne principles of respect, knowledge, wisdom and spirituality. Fundraising is ongoing, and donations are graciously accepted at rtc.li/ncb-legacy-fund.

A Path Forward

“As we talked, it became evident that we’d had both Cheyenne and non-Natives working on the monument,” said Major Robinson, and its development “was already causing healing.” Could a trail take this even further?

If the monument was a look back to sacrifices made, the trail would be a path toward future healing.

As he had already led the monument’s development, Major Robinson and his Native-owned Redstone Project Development company were tapped to lead the design and construction of the Northern Cheyenne Healing Trail. Slated for completion in 2025, the nearly 4-mile Healing Trail of crushed aggregate will run from Fort Robinson State Park alongside towering sandstone buttes. Connecting on either end to the White River Trail, it will become part of the country-spanning Great American Rail-Trail®. The Healing Trail will include interpretive signage about the Northern Cheyenne’s escape from the fort and will lead travelers to the Northern Cheyenne Monument.

The Healing Trail will offer striking views, said Major Robinson, but will be about much more than scenic beauty. “We’re asking travelers to slow down and absorb what’s around them with different reflection points along the way,” he said. While bikes will be welcome on the segment, “it’s not meant to just be zipped on through.”

So why a healing trail when an anger or resentment trail might seem more fitting? It’s true, agreed Major Robinson, that the U.S. government “looked at our ancestors as animals that needed to be removed from the face of the Earth; I think we have every right to feel that—but it keeps us stuck in that moment and controls us,” he continued. “We’re all healing from something, and I hope that people who come and experience this reflect on these amazing people and the children who were never allowed to have their own story. Can we do better and treat each other better—and in the process heal a part of ourselves?”

The monument and trail will work in concert to tell the Northern Cheyenne’s story and inspire future generations to do better, said Whitecrane. Reflecting on the actions of his ancestors at Fort Robinson, Whitecrane said, “We’re so proud of the people that did that for us. We don’t want to focus on hatred, anger. The Healing Trail is going to be a big part of that.”

Related: Northern Cheyenne seek to commemorate escape with trail | Flatwater Free Press

This article was written as part of History Along the Great American Rail-Trail®, a project of TrailLink.com™ highlighting hundreds of stories and historical points of interest along the 3,700-mile route. It was originally published in the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of Rails to Trails magazine and has been reposted here in an edited format.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.