Taters and Trains: The Great Big Baked Potato and the Northern Pacific Line

“The only way [for the major passenger lines] to set themselves apart was through the food they served on the train. It was that kind of competition that drove the cuisine.”

—James D. Porterfield, Author, “Dining by Rail”

Any optimist worth their sunny disposition knows what to do when life hands them lemons, but what about when those lemons are supersized, unwieldy potatoes unfit for the refined palate? Make them the centerpiece of your railway marketing campaign. Obviously.

The year was 1908; Hazen Titus was the new superintendent of dining cars for the now-defunct Northern Pacific (NP) Railway when he overheard a conversation between two passengers that would result in the NP’s dining cars catapulting ahead of the competition and cementing the railway in the public’s imagination.

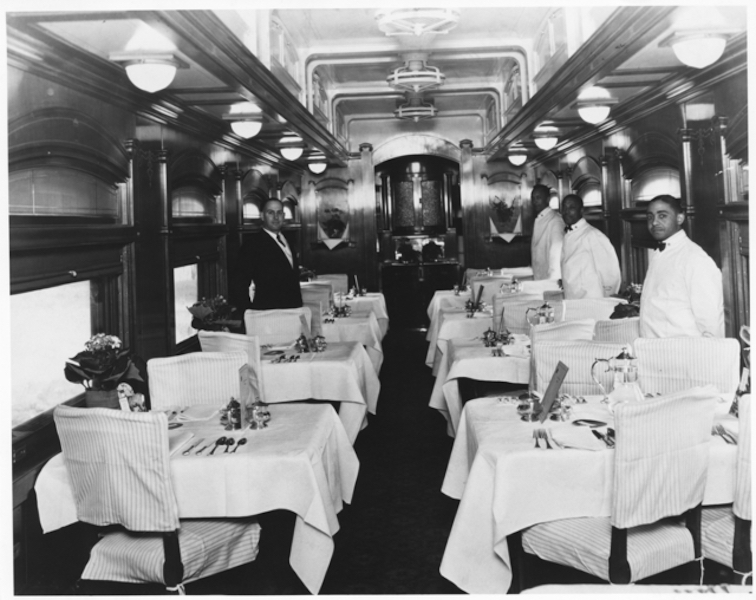

Before getting into all that, though, it’s necessary to pause here and consider what a grand experience train dining once was: To a modern consumer, the concepts of mass transit and fine dining are worlds apart, and anyone who’s ever settled for a premade, cellophane-wrapped sandwich from the walk-up counter of a modern passenger train could be forgiven for thinking it was always thus. But at the time Titus assumed leadership of the NP’s dining operations, the dining cars found in most of the country’s passenger trains were no mere rolling cafeterias.

Indeed, they offered some of the finest culinary experiences around, rivaling the country’s fanciest restaurants—all in kitchens a fraction of the size that swayed nonstop.

With linen cloths, beautifully decorated high-end china, actual silver cutlery and a team of attendants, the dining car of a premier passenger line offered a meal not easily forgotten—so much so that passengers of means purportedly would ride simply for the meals.

“That’s how the railroads distinguished themselves—with their cuisine,” said James D. Porterfield. An authority on railcar dining facilities, he’s the author of “Dining by Rail,” a book chronicling the history and recipes of America’s Golden Age of railroad cuisine. All the passenger lines used railcars “manufactured by the same companies, so there was little to no variation in those,” explained Porterfield. Neither was speed much of a differentiator: “There were four major passenger lines between Chicago and Minneapolis alone; they all took different routes, but they all did it in 400 minutes,” continued Porterfield. So what was left? “The only way to set themselves apart was through the food they served on the train. It was that kind of competition that drove the cuisine.”

The Great American Rail-Trail and the

Northern Pacific Line

The Northern Pacific served both passengers and freight, and two trails of the Great American Rail-Trail™ follow the path of old freight lines.

The Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes runs 73 paved miles through Idaho’s scenic panhandle. Wildlife abounds, and the trail skirts the north side of Wallace, home of the Northern Pacific Depot Museum. Shauna Hillman, the museum’s former director, often rides the trail on her kick scooter. “The trail is a fantastic addition to the area and the story of the old mining camps here,” she said. “The history of Wallace reads like a dime novel: Murder, mayhem, mining, money and the railroad.” The depot museum in Wallace is a popular trailhead with ample parking in the museum lot, restrooms and a water-filling station.

The 22 miles of the NorPac Trail cross the border between Idaho and Montana. With rugged natural surfaces, the route is best suited for mountain bikes. Note that the U.S. Forest Service closed the Borax Tunnel this summer over structural concerns; a quarter-mile bypass route exists, but the steep and rocky route is difficult to ride and may necessitate walking your bike along this section. No plans for the tunnel’s reopening have yet been released.

From Problem Potatoes to Stupendous Spuds

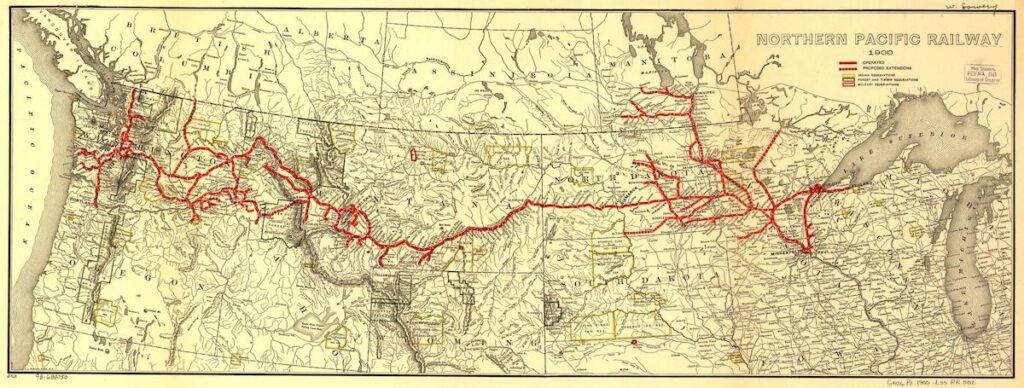

Titus was a couple months into his new position as head of the NP’s dining operations when he undertook a familiarization trip across the NP line, an empire that stretched across the northern United States from the shores of Lake Superior to the Pacific Ocean. It was aboard the NP’s flagship passenger train, the North Coast Limited, that he overheard two farmers lamenting the potato crop coming out of their farms in Washington’s Yakima Valley. The tubers were simply too big.

At a time when delicate, petite potatoes were the preferred choice across the country, there was simply no demand for large spuds with leathery, wizened skin; some were tipping the scales at an almost unbelievable five pounds. Joining in the farmers’ conversation, the dining car superintendent was surprised to learn that without a market for their generously sized potatoes, they were destined to be sold for a pittance as hog slop. Titus had a better idea.

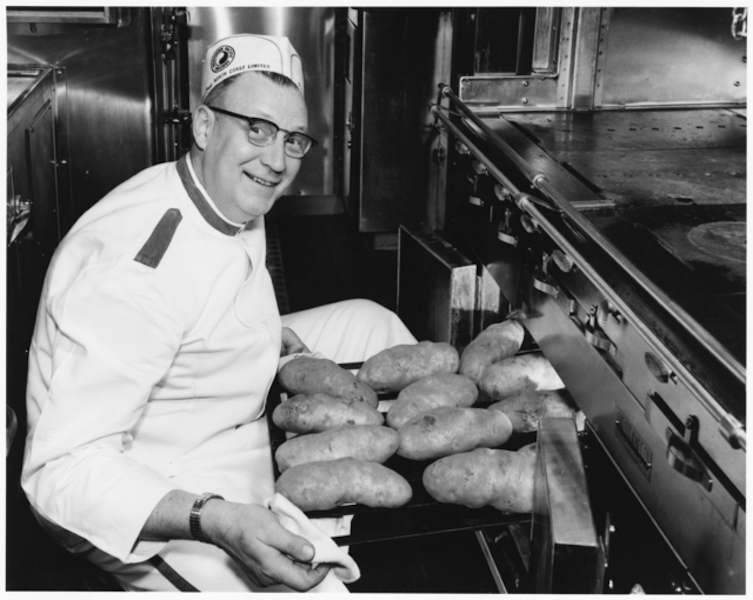

Detraining with the farmers in Yakima, he obtained a bushel of the potatoes and brought them to the NP’s commissary in Seattle where he got to work with a team of cooks experimenting with different cooking methods. The problem to overcome, explained Porterfield, was that without special preparation, such large potatoes “would burn on the outside and still wouldn’t even be cooked on the inside.” The solution, continued Porterfield, was a special rack the railway designed with a kebab-like spike that transferred heat into the potato, providing well-rounded cooking.

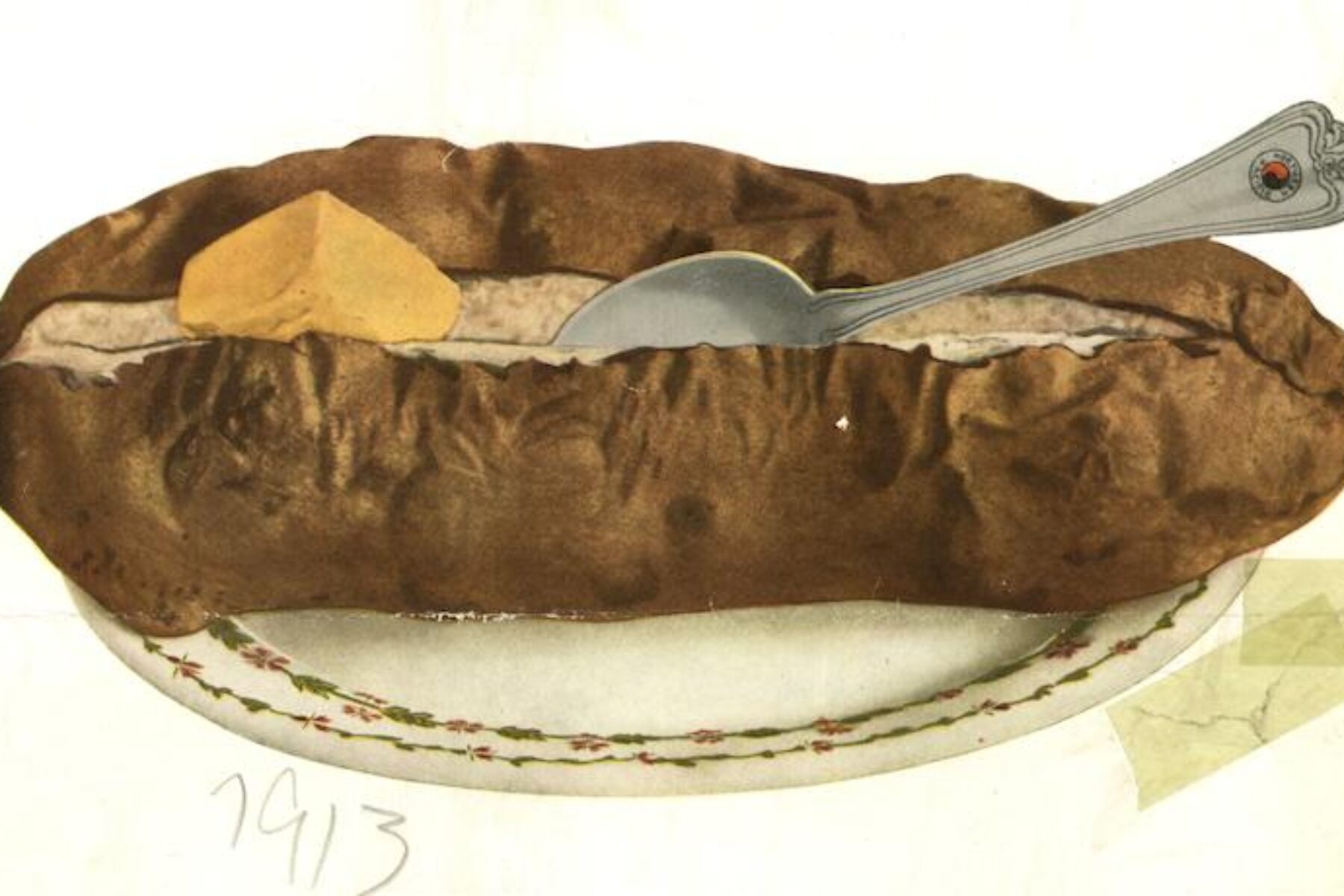

The perfect spud was found to be around two pounds, and two hours of baking resulted in a tender and creamy delight; topped with a generous pat of butter and eaten with a spoon, the potatoes were ready to shine.

Titus started ordering supersized potatoes in earnest, and it was just weeks later, in early February 1909, that the first of these great big potatoes was served aboard the North Coast Limited at the price of an even dime. The NP would never be the same.

A Marketing Campaign Sprouts

It didn’t take long for the railway to make these potatoes of unusual size the centerpiece of its marketing efforts for the next 50 years or so. As described by William McKenzie in his book “Dining Car to the Pacific,” the Northern Pacific created a plethora of marketing tchotchkes: spoons, letter openers, inkwells, blotters, medallions, mechanical pencils, statuettes, aprons and postcards galore—all featuring the railway’s signature giant tuber split down the middle with a spoon on one side and a great big pat of butter on the other.

A brochure estimated to be from the late 1930s proudly noted that each year the line went through some 14 tons of coffee, 27 tons of butter, 50 tons of poultry—and 265 tons of potatoes. Even the line itself became known as the “The Route of the Great Big Baked Potato.”

Famous actors of the day promoted the tremendous tubers, and when an addition was built to the line’s Seattle commissary—the same one in which the baked potatoes were first perfected—it was topped with a 40-foot-long light-up spud. The NP was all-in on its potatoes.

The runaway success of the Great Big Baked Potato spawned competition among the railways. The Great Northern Railway, a competitor to the NP, “was not to be outdone,” said Porterfield. “They answered with a Baked Wenatchee Apple,” featuring fruit grown in the eponymous Wenatchee Valley. Like their root vegetable competition, the apples were improbably large, some two and a half times larger than a modern McIntosh. After being partially peeled and cored, the apples were filled with sugar and baked. “It was a candied apple by the time it came out of the oven.”

The sweet treats were offered at breakfast, lunch and dinner.

The End of the Line

Even judged by the tumultuous standards of turn-of-the-century railroads, the NP had a rough go of it in the beginning and a subsequent history full of financial hardships. It’s perhaps not surprising considering that much of the NP’s route was constructed through rugged lands and territories not yet admitted to the Union as states; much of it traced the path that the famed Lewis and Clark expedition had explored decades earlier.

After being completed in 1883, the NP survived on its own until merging with other lines in 1970 to form the Burlington Northern Railroad; the Burlington Northern later merged with the Santa Fe line in 1996 to become the modern BNSF.

The light-up spud atop the NP’s commissary may be gone, and its fine dining cars are no more, but traces of the NP’s past can be found in museum depots: the Northern Pacific Railway Museum in Toppenish, Washington, is open May–October and features a depot, steam train, freight cars and a caboose. The Northern Pacific Depot Museum in Wallace, Idaho, is also open seasonally, April–October; this re-creation of an early working railroad station is located in the center of the universe—really! A manhole cover at Sixth and Bank Streets proclaims this to be true, and it hasn’t yet been disproven.

And the route that the NP blazed is still alive today in a country-spanning rail-trail: both the Trail of the Coeur d’Alenes (named for the region’s indigenous tribe) and the NorPac Trail (named for the Northern Pacific, of course!) are built along parts of the NP’s route, and both are segments of RTC’s Great American Rail-Trail.

RELATED: History Along the Great American Rail-Trail: A Kick-Off With the Creators

This article was written as part of History Along the Great American Rail-Trail™, a project of TrailLink.com™ launching in Fall 2021 and highlighting hundreds of stories and historical points of interest along the 3,700-mile route. It was originally published in the Fall 2021 issue of Rails to Trails magazine and has been reposted here in an edited format.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.