American Icons: Rail-Trails That Helped Shape the National Landscape

In September 1963, the Chicago Tribune published a reader’s letter titled “Future Footpath,” which was authored by an esteemed 70-year-old naturalist named May Theilgaard Watts. The letter extolled the virtues of developing a trail along the disused Chicago, Aurora & Elgin Railway corridor connecting Chicago and its western suburbs—a call to action to preserve the region’s tallgrass prairie, connect critical garden and ecology centers, and provide a footpath with a separated bikeway for the community.

Not long after, in 1964, the state of Wisconsin had taken an interest in a section of the Chicago and North Western Railway (C&NW), from Elroy to Sparta, which saw its last service that year and was up for abandonment. Having received appeals from locals to preserve the line as a hiking asset, the Department of Conservation (now Department of Natural Resources, or DNR) set out to analyze its potential as a “linear recreation way,” deploying a small team to assess the corridor. That team would greenlight the project, recognizing the small—but manageable—challenge that the grade in some parts of the route might present to bicyclists.

Differing greatly in their development, there has long been friendly debate about which project can be considered America’s first major multiuse rail-trail. But what is widely accepted is that both projects—which would come into being within just a few years, as the Illinois Prairie Path and Elroy-Sparta State Trail—served as the earliest major blueprints of the rail-trail movement.

And, in less than three decades, this movement would spread—from the Midwest to the entire country.

America’s First Rail-Trails

Ahead of Their Time

In the 1960s and ‘70s, the term rail-trail was not part of America’s vernacular. The creation of the now 62-mile Illinois Prairie Path and 34-mile Elroy-Sparta State Trail were the Midwest sparks of the movement.

According to Peter Harnik—who co-founded Rails-to-Trails Conservancy (RTC) in 1986 and is the author of an upcoming book, “From Rails to Trails: The Making of America’s Active Transportation Network,” to be published in May of 2021—these two trails stand out for the ways they prompted either strong citizen advocacy or governmental action, “the first being in a major metropolitan area, and drawing a lot of media attention and thousands of citizen supporters to its cause, and the second, a rural project eliciting early planning and support by the state.”

However, the concept of converting a railroad corridor into a trail wasn’t quite a new one. By the 1960s, some 30+ quiet rail-trail conversions had already been created—mostly in “remote backcountry locations … having been absorbed into the surrounding state or national forestlands and incorporated into the hiking systems,” said Harnik.

Examples include New Hampshire’s 4.1-mile Osseo Trail in White Mountains National Forest (circa 1905), and Pennsylvania’s Stony Valley Railroad Grade, which was created in 1949 and runs through a state game land for almost 20 miles in the Appalachian Valley and Ridge region.

The Cathedral Aisle Trail, a 1-mile walking path, created in South Carolina in 1939, has unique origins, inhabiting an old hunting preserve that was converted to a protected natural area that year.

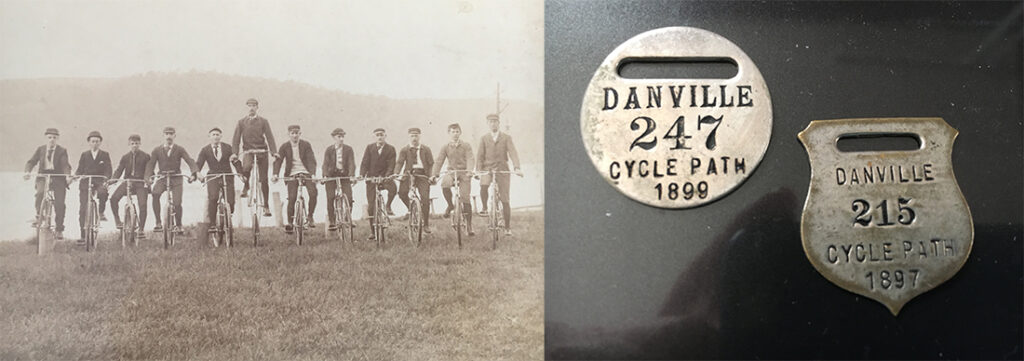

But there is one story of early community organization around a trail before the 1960s, that of the J. Manley Robbins Trail in Danville, Pennsylvania, which—tracing back to the 19th century—is the oldest known rail-trail in the United States.

The 1.1-mile trail, which connects to the Old Reading Line Trail to form the 2.6-mile Hess Loop Trail, first saw organized use by the Danville Bicycle Club in the 1890s, according to local historians Helen “Sis” Hause and Van Wagner. The corridor, built on a former narrow-gauge railroad by the Montour Iron Works in the 1840s, had also seen prior use, having “been traveled by a man named Phillip Maus,” who had a grain mill in the area that became Mausdale, at the far end of the trail. Maus used the corridor “to take the products of his mill to town by horse carts.”

“By 1897, a bike club was selling memberships for the operation and maintenance of the trail,” said Bob Stoudt, director of the Montour Area Recreation Commission. “In the 1900s, [oversight] of the trail went back and forth between volunteer groups, and sometimes [fell off the radar], but in the early 2000s, people realized it was an important legacy, and we couldn’t let it fall into disrepair.”

“When [the commission] was formed in 2005 … our first task was to take care of the trail, and make it into a community and regional asset,” added Stoudt.

Today, the trail is used by some 25,000 people a year—though Stoudt estimated 40,000 trail users by the end of 2020—and the trail is part of the commission’s aggressive future plans to make Montour County a regional destination.

Preserving an Illinois Legacy

May Theilgaard Watts’ visionary 1963 Chicago Tribune letter, which set the stage for the Illinois Prairie Path, is best understood in the context of Watts’ passions as a teacher and naturalist, during a time when the environmental movement—impelled by Rachel Carson’s 1962 book, “Silent Spring”—was in its infancy.

“The big impetus was not recreation first and foremost,” explained Jerry Adelmann, president and CEO of Openlands, which helped create the trail in the 1960s. “It was to save the prairie remnants and open space [that existed along the corridor].”

“We are human beings,” wrote Watts. “We need a footpath …. The right-of-way of the Aurora electric road lies waiting …. The path lies ahead, curving around a hawthorn tree, then proceeding under the shade of a forest of sugar maple trees, dipping into a hollow with ferns, then skirting a thicket of wild plum, to straighten out for a long stretch of prairie ….”

She ended with an ominous tone: “Right now … many hands are itching for it. Many bulldozers are drooling.” In the book “City of Lake and Prairie,” editor William C. Barnett noted Watts’ great dismay at the destruction of open space brought on by development in DuPage County, which lost 90,000 acres of farmland between 1945 and 1975. He also noted the early grassroots nature of the Prairie Path effort, which was driven by women.

Watts had built a large constituency of females through her work at the Morton Arboretum and garden clubs—engaging mothers, teachers, families and Scouts—and they would form the backbone of the Prairie Path effort. This included a core group that “created a publicity campaign, giving well over [100] presentations at libraries, schools, and town halls.”

In 1963, the Openlands Project (now Openlands) was established in Chicago to “seek preservation and development of recreation and conservation resources” in the region. With leadership from Gunnar Peterson, its first executive director—who later helped establish the National Trails Council in 1972—the Openlands Project offered vital technical expertise for the development of the trail, which involved lengthy negotiations with the railroad, utility companies and local governments.

“Watts was the grande dame of conservation in our region,” said Adelmann. “Gunnar provided office space and staff support, as well as links to philanthropists and funding, and technical and legal help as they were putting the trail together.”

The Illinois Prairie Path Not-for-Profit Corporation (IPPc)—which was formed in 1965—lists 14 founders in its online history of the trail, who engaged thousands of people and involved public officials at the local, state and national level. In 1966, just 953 days after Watts’ letter was published, they succeeded in acquiring a lease via the IPPc with DuPage County—which had initially wanted to break up the right-of-way for other uses—for the first 27 miles of trail. In 1972, two additional branches were extended to Elgin and Aurora in Kane County.

During the national liability insurance crisis in 1986, the IPPc handed over the maintenance of the pathway to DuPage County, but since that time has remained the central advocacy voice and entity for improving and promoting the trail. Today, the trail sees hundreds of thousands of visits a year by individuals who value the corridor for the many opportunities it brings for physical activity, commuting, connecting to nature and economic vitality.

“Initially the municipality did not like the idea of trails—they weren’t supportive,” said Erik Spande, an environmental scientist and the village president of Winfield, Illinois, who has served as IPPc Board president since 2013. “What they have found since then is that trails are valued infrastructure that emphasize the ‘triple bottom line’: health and wellness, the environment, and the economy.”

He continued, “[The trail] enriches people’s lives, and helps the community; it’s an increasingly valuable [piece of] urban infrastructure. I occasionally get a chance to chat with young people, and they say they can’t imagine their life without the Prairie Path system. We’ve gone from ‘a crazy idea’ to something people want and use every day.”

Related: May Theilgaard Watts’ 1963 letter to the Chicago Tribune.

Boundaries of the World

The development of the Elroy-Sparta State Trail took on a different form in 1964. In an “Oral History” created by the Wisconsin DNR for the trail’s 50th anniversary, Bob Espeseth, then-chief planner for the Forests and Parks Division, said that at that time, Wisconsin outdoor recreational space was on the rise; in fact, the state saw “the greatest growth of the state park system in its history” adding “19 new properties … as a result of a cigarette tax advanced by Governor [Gaylord] Nelson.”

Local leaders and groups were pushing for the trail, which was received well in town meetings—though not without opposition; early supporter Lyda Lanier noted concerns by local farmers that “bicyclists would open the gates and let the cows out.”

The Interstate Commerce Commission authorized the Elroy-Sparta section of the C&NW corridor to be abandoned in 1964, and in 1965, while still negotiating its purchase, the state designated the corridor a trail. The railroad removed the tracks but left most of the structures intact, and the final purchase of 32 miles was concluded in 1966 for just $12,000—an amount considered in rail-trail circles as the “deal of the century.”

Today, the Elroy-Sparta is a showcase of America’s rural heartland, connecting five communities and featuring three famous tunnels—one stretching 3,800 feet. Further connections can be made via the 400 State Trail and Omaha Trail in Elroy, and the La Crosse River State Trail in Sparta, the “Bicycling Capital of America.”

Initially, the trail was unsurfaced, with no railings along trestles, and difficult to ride, and creators mentioned reports of accidents and “close calls” in the early days. Bicycling was added to the plans in 1966, and the trail was fully surfaced by 1970. With these enhancements, the Elroy-Sparta became an early marker for a later signature of trail development: bike tourism.

Prior to the Elroy-Sparta, said Lanier, they didn’t view long-distance bicycling as a recreational pursuit. But when the trail came through, she and her husband, Edwin—who found it hard to travel with work and four children—saw an opportunity to transform an empty farmhouse they owned into a hostel, to generate income and introduce their kids to interesting people from other places. After the Farmhouse Youth Hostel at Ridgeville was advertised in the American Youth Hostel handbook, bikers did come, said Lanier—from all over the globe, including Germany, Israel and South Africa.

In 1967, about 4,000 people used the trail. By the mid-1980s, trail managers were recording some 60,000 annual users.

“I like to say the boundaries of Ridgeville are the boundaries of the world—and I think that [the trail] has done that for all of us. Brought the world to us,” affirmed Lanier.

Related: View an interactive StoryMap on the Elroy-Sparta State Trail.

The Making of Massachusetts Shining Sea Bikeway

An excerpt from Peter Harnik’s book, “From Rails to Trails: The Making of America’s Active Transportation Network,” by the University of Nebraska Press (2021):

In 1968 the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad announced the abandonment of the last 11 miles of its [Massachusetts] route from North Falmouth south to Woods Hole. Two mothers, Joan Kanwisher and Barbara Burwell, had already known of the likely abandonment and had been organizing in favor of public acquisition for a trail they were calling the Shining Sea Bikeway in honor of a Falmouth native, Katherine Lee Bates, who composed the song “America the Beautiful.” On April 2, 1969, they secured the town’s solid agreement to a purchase, but on the next day came the stunning revelation that the railroad had secretly sold the land to a private individual and that he was unwilling to allow a trail.

Five years of expensive and divisive legal wrangling followed, all the way to the state Supreme Court, before the town finally prevailed. The outcome was quadruply momentous: The rail-trail became the first in Massachusetts; the trail became the first in the nation’s history to be reassembled by eminent domain (condemnation by the town); the effort was profoundly inspirational to Barbara Burwell’s son, David [co-founder and first president of Rails-to-Trails Conservancy]; and the legal struggle led to the passage of the strongest state rail corridor protection legislation in the country.

Harnik’s book will be published in May 2021. The book is available for preorder here.

Related: Beautiful Inspiration: From Sea to ‘Shining Sea Bikeway’

Pulses of the Movement

Seattle’s Heart Line

The Burke-Gilman Trail in Washington State is a paragon of Western rail-trails. Dubbed in a 2014 Rails to Trails article as the “Heart Line” of Seattle, it “pulses with activity year-round, and the volume rarely slows, even during the soggiest winter months,” wrote former Editor-in-Chief Karl Wirsing.

From Golden Gardens Park on Puget Sound, the trail heads into northern Seattle neighborhoods and passes directly through the University of Washington. From there, it edges along Lake Washington, featuring views of Mount Rainier, before curling around the lake’s northern tip toward Bothell and merging with the Sammamish River Trail.

Tracing back to the early 1970s, the Burke-Gilman—which inhabits a rail corridor discontinued in 1971—is the product of an advocacy effort sparked after opposition threatened its development, and which drew major attention from the media and public leaders.

According to Harnik, when a wealthy neighborhood opposed the trail, and the railroad seemed to align with the opposition, supporters rallied, including the local bicycling and recreation community, Mayor Wes Uhlman and even Sen. Warren Magnuson, then-chairman of the Senate commerce committee.

“Burke-Gilman was truly an urban trail that involved the entire pro-trail citizenry and the governments of Seattle and King County,” said Harnik. “It was a full-fledged early showdown between pro- and anti-trail people, with the railroad caught in between.”

The first 12.1-mile piece was created in 1978. Later, “when the railroad sold off additional portions of the corridor, lawyers got involved and brought enough legal action that the railroad had to unwind and sell to the city.”

The trail eventually expanded to 18.8 miles, with much media coverage, citizen action and local governmental support. Today, the Burke-Gilman, managed jointly by the City of Seattle and King County Parks, is a staple for commuting, recreation and fitness, receiving hundreds of thousands of visits each year.

FUN FACT

The Burke-Gilman Trail in King County is a valued community asset, with the King County section receiving an estimated 450,000+ visits annually, and a popular segment in Seattle, near 70th Street, receiving more than 500,000 visits in 2019.

Rail-Trail Pilot Program

The Railroad Revitalization and Regulatory Reform Act (4R), the first law to deregulate the railroad industry (the Staggers Act followed in 1980), was passed in 1976. “This legislation was incredibly impactful for the movement,” said Marianne Wesley Fowler, RTC’s senior strategist for policy advocacy. “It unleashed a massive abandonment by railroads all over the country … inventory for potential rail-trail conversions became available, and communities responded.”

Also of note was a section in the legislation creating a rail-trail grant program, which, in October of 1977, announced $5 million (in matching funds) available for interested projects. Of the 135 applications received, totaling some $70 million, nine projects were accepted, including: Washington & Old Dominion Railroad Regional Park (W&OD Trail) in Northern Virginia; the Palmer County/Bethlehem Trail in Pennsylvania; the Mohawk/Hudson Bike-Hike Trail in New York; the Little Miami Scenic Trail in Ohio; the Torrey C. Brown Rail Trail in Maryland; the MKT Nature and Fitness Trail in Missouri; the Preston-Snoqualmie Trail in Washington; the Marin Trail (Mill Valley/Sausalito Multiuse Pathway) in California; and the Delaware & Raritan Canal State Park Trail in New Jersey.

The program “got publicity and gave the movement a tremendous shot in the arm,” said Harnik.

All nine projects were eventually successful, and many gained national prominence. Virginia’s W&OD Trail—connecting communities, green space and civic centers across 45 miles in Arlington, Fairfax and Loudoun counties near Washington, D.C.—would serve as an influential model for RTC’s Congressional advocacy efforts in the late 1980s. The trail—which is owned and operated by the Northern Virginia Regional Park Authority, and maintained in partnership with Friends of the W&OD Trail—was known and used by members of Congress and staffers who lived along the corridor. “They could understand what we were talking about when we said ‘rail-trail,’” Harnik affirmed, “because they had actually biked or run on it.”

Learn more about the Capital Trails Coalition and seven other trail networks comprising RTC’s TrailNation™ portfolio.

Today it’s a western linchpin in plans by the Capital Trails Coalition, an RTC TrailNation™ project, to create an equitably distributed 800-mile trail network in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan region.

Another incredibly impactful pilot, said Fowler, was the trail in Marin County, California, which helped “set off a [regional] active transportation movement.” In the 2000s, the Marin County Bicycle Coalition would serve as a lead advocate for the Safe Routes to School program, which became a fully funded national program in Congress’ 2005 SAFETEA-LU legislation. The coalition was also vital to the passing that same year of the Nonmotorized Transportation Pilot Program—for which it served as one of four pilot communities. The program would avert 85.1 million vehicle miles between 2009 and 2013.

And in Columbia, Missouri, which also served as a Nonmotorized Transportation Pilot Program community, the 9.3-mile MKT Trail became an important precursor to one of today’s most iconic trails, the 240-mile Katy Trail State Park stretching almost across Missouri, with some of the same developers who worked on the MKT going on to build the Katy.

FUN FACT

The effort for Washington, D.C. and Maryland’s 11-mile Capital Crescent Trail involved a coalition that was launched by RTC co-founder Peter Harnik in 1986 and that grew to 38 outdoor organizations. Learn more.

National Trails System Act and Railbanking 101

A Good Little Law

In 1986, Rails-to-Trails Conservancy opened its doors. Launched by co-founders Peter Harnik and David Burwell (RTC’s first president), and attorney Charles Montange, RTC is now the largest advocacy organization for trails, walking and bicycling in the country.

Three years prior, another milestone—a legislative breakthrough—took place that would send ripples through the trail world. That milestone was railbanking, and the author of the legislation was a National Park Service staffer named Pete Raynor.

Related: Central Author of Historic Trail Legislation Named 2018 Doppelt Family Rail-Trail Champion

The National Trails System Act (NTSA) of 1968 had created the nation’s first National Recreation Trails, including the Appalachian Trail and the Pacific Crest Trail. By the early 1980s, railroads were being abandoned in large numbers; however, railroad easements had been proving problematic for the development of the Appalachian Trail in particular.

With leadership from Rep. Phil Burton of California, then-chairman of the House subcommittee on national parks, Raynor set about updating the NTSA with what he calls a “good little law” that he believed, with powerful simplicity, could be extremely impactful. “How about a ‘bank’ for railroad corridors?” he hypothesized. That way, the corridors could be saved for future use, via interim use as trails.

The statute—just two sentences—was first added to the NTSA bill in 1981 and received wide Congressional support. The bill was passed in the 98th Congress and signed into law by President Reagan in March 1983.

Railbanking had an immediate impact in Iowa, the first state to take advantage of the statute. As long-time Iowa trail advocate Tom Neenan, who passed away in 2015, wrote in a Summer 2006 Rails to Trails reader’s letter, “The Iowa Trails Council was conceived in 1983 and officially formed in 1984, almost solely because of the 1983 amendment ….”

Two notable railbanked projects in the state include the 33-mile Sauk Rail Trail in Carroll and Sac counties, born in the mid-1980s from the first railbanking application ever to be filed, and the 52-mile Cedar Valley Nature Trail, which debuted in 1984 as Iowa’s first completed rail-trail, a project of the council, the Iowa Natural Heritage Foundation and RTC. Initially receiving strong opposition, the trail is a beloved regional asset today and serves as the state’s gateway for the developing 3,700-mile Great American Rail-Trail™.

The Great American Rail-Trail comprises 145+ host trails on a 3,700-mile route from Washington to Washington. Learn more about the route.

Trails From Influential Court Cases

Railbanking was challenged early in its existence (and these challenges continue today) in court cases that helped make some of the country’s most renowned trails possible.

After the state of Missouri’s application to railbank a 200-mile section of the disused Missouri-Kansas-Texas Railroad outside St. Louis was approved in 1987, 144 adjacent landowners filed a lawsuit challenging railbanking’s constitutionality. The ruling by the 8th Circuit District Court in 1989, in favor of the trail manager (the Missouri Department of Natural Resources), was a huge win for trails, “restricting the jurisdictions of the courts over legal challenges by adjacent landowners, except in limited circumstances,” said Andrea Ferster, RTC’s general counsel since 1992.

Notably, the Katy Trail, early in its development, had received $2.2 million in funding support from Pat and Ted Jones (founder of Edward Jones Investments)—the latter of whom had drawn inspiration from another iconic trail, the Elroy-Sparta. By the time of its completion in 2011, the Katy Trail, which connects three dozen communities, had become synonymous with rural trail tourism (discussed later).

Related: Pathway to Prosperity: Missouri’s Katy Trail Is a Beautiful Model for Commerce

As the 1980s came to a close, another legal case came about in Vermont that, according to Ferster, is the most influential rail-trail case in the movement’s history. Involving the railbanking of 8 miles of the Vermont Railway in 1987 to create the Burlington Bike Path, the case—Preseault v. the United States—reached all the way to the Supreme Court, whose 1990 ruling unanimously upheld the constitutionality of railbanking. “It was a foundational case for establishing railbanking as a legitimate exercise of governmental power,” said Ferster.

At the outset, the ruling enabled the Burlington Bike Path’s development and evolution into the 13.4-mile Island Line Rail Trail, a spectacular pathway running from Burlington, and across the 3-mile Colchester Causeway over Lake Champlain (with a 200-foot ferry ride), to Lake Hero Island. Managed by the nonprofit Local Motion, the trail is a beloved local asset and international tourism draw.

Related: Rail-Trail Cases That Have Shaped the Movement

Railbanking would have a significant and lasting impact, making some 175 additional rail-trails possible over the next three decades.

FUN FACT

Railbanking set the stage for Nebraska’s developing Cowboy Recreation and Nature Trail, which is currently the longest rail-trail project in the country at 321 miles.

Into the Roaring ’90s and Beyond

Wings of the Southern Rail-Trail Movement

In the late 1980s, the Southern rail-trail movement began to take flight. When Tennessee-bred Marianne Wesley Fowler came to RTC in 1988 as the Southern coordinator, “there were [well-known] rail-trails in just two Southern states,” she affirmed. These included: Virginia’s W&OD Trail near the U.S. capital; the Virginia Creeper National Recreation Trail connecting White Top and Abingdon; and Florida’s Tallahassee-St. Marks Historic Railroad State Trail.

“I decided the best strategy was to have a highly visible, wonderful trail in each state—the closer to the state capital, the better … because the lives of these states revolved around the state capitals,” said Fowler.

RTC looked first to Atlanta, but a series of studies revealed almost no disused rail corridors—“It was a thriving commercial center, not a declining industrial area,” said Fowler. Those studies, however, did provide the contacts needed to help generate support for two potential conversions on the radar—one stretching from Piedmont, Alabama, to just over the Georgia border; and the other running from Rockmart, Georgia, to “Etna” (which, after a muddy trudge, was revealed to be a utility box stenciled with the letters “ETNA”, near Smyrna).

The first, the Chief Ladiga Trail, saw initial opposition—“We don’t do rail-trails,” the mayor of Piedmont, who did not believe the corridor would be abandoned, told Fowler. After the abandonment, that same mayor—appreciating Fowler’s foresight—turned into one of the greatest supporters of the trail, which opened its first section in the mid-1990s.

For the latter, “The Georgia Rails Into Trails Society [GRITS] became very active, and we went through the process of convincing the Georgia Department of Transportation to put the corridor into public ownership,” said Fowler. This project, with later crucial leadership and support by the Path Foundation as well as three counties and four cities, saw its first segment open in 1998 as the Silver Comet Trail.

In 2008, the 61.5-mile Silver Comet Trail and the 33-mile Chief Ladiga Trail were connected, creating one of the longest continuous paved pathways in America.

“If you had told me 30 years ago that a 94.5-mile trail connecting Anniston, Alabama, with Smyrna, Georgia, would have been possible, I wouldn’t have believed it,” said Fowler, in a Spring/Summer 2016 Rails to Trails profile.

But, Fowler emphasized, an important strategy for successful rail-trail development is choosing targets of opportunity. “That’s what made the Silver Comet, just outside of Georgia’s state capital, such an important early target,” she said. “And knowing that the Chief Ladiga … could meet with the Silver Comet at the state border to create a continuous system was very compelling.”

Related: Rails to Trails Green Issue 2014: The Southern Rail-Trail Movement

DID YOU KNOW?

The vision for Florida’s Pinellas Trail began in 1983, after a 17-year-old boy was killed while riding his bike on the Belleair Causeway. Today, the trail, which opened its first section in 1990, is one of the most used in the country. Learn more.

Paradigm Shift

In 1991, a federal transportation bill was signed into law by President George H. W. Bush that introduced the nation’s first dedicated funding programs for trails: Transportation Enhancements (now Transportation Alternatives) and the Recreational Trails Program.

Since 1991, more than $15 billion has been dedicated for trails, walking and bicycling projects through these programs, which have been vital to trail development in all 50 states.

By the end of the 1990s, America surpassed 1,000 known rail-trails. By 2020, more than 40,000 miles of multiuse trails covered America, including 24,000+ miles of rail-trails. And as the movement evolved, so too did another paradigm—the impact of rail-trails as economic and tourism generators, for small town revitalization, and for regional competitiveness.

“Initially, rail-trail development was about preservation—the opportunity to preserve open space that would have otherwise been lost—and recreation, creating places where people could go out and enjoy nature,” said Keith Laughlin, president of RTC from 2001 until his retirement in 2019. “But over time, we [as a national movement] began to see the economic benefits, the health benefits, that just started piling up as more trails got built.”

Laughlin mentions one of the first to resonate on a national level—the Katy Trail—which has evolved since 1990 to become a premier tourist attraction in Missouri, drawing some 400,000 people annually, with towns that welcome trail users to their restaurants, shops, lodging establishments and other attractions. A 2012 study by Missouri State Parks found the Katy had a direct economic impact of $18.5 million annually.

“It was one of the first trails where we had this idea of the ‘trail town,’” noted Laughlin. “It really captured people’s imaginations.”

Another trail to make enormous economic waves in the 2000s: the 150-mile Great Allegheny Passage (GAP) (gaptrail.org), which connects 15 mostly former industrial communities between Pittsburgh and Cumberland, Maryland, that have reinvented themselves as trail towns. The trail connects to the C&O Canal Towpath for a seamless 334.5-mile route between Pittsburgh and Washington, D.C. A valued asset by local residents, and a tourism draw for people from around the world—the GAP attracts nearly 1 million visitors annually and generates tens of millions of dollars per year in trail-user spending. Both trails also serve in their states as gateways of the Great American Rail-Trail.

Over the past 20 years, rail-trails have shifted in the minds of America’s collective consciousness. The early rail-trails were models for those that came after—and all have worked together to demonstrate the power of trails and make the case for their development nationwide.

“Thirty-five years since RTC first started, trails can now be found in the cities, towns and countryside of every state, and our country is better for them. Millions of people enjoy the economic, health, environmental and transportation benefits they bring to communities,” said RTC President Ryan Chao. “Now more than ever, we understand as a nation how essential safe, equitable access to these vital outdoor spaces is for all people. As RTC continues to connect the nation by trail, we do so with deep appreciation for all the people and trails that helped build our thriving movement.”

RTC’s co-founder, the late David Burwell, said in a 2006 Rails to Trails interview, “My dream is that one day you could go across this entire country … on flat, wide, off-road paths. I want rail-trails to be America’s main street.”

Now, his dream is becoming a reality the same way the early founders took their individual visions and collectively ingrained a new paradigm: their communities, and a nation, made better by trails.

Related

- In February 2021, RTC celebrates its 35th anniversary! Check out an interactive timeline of major milestones for RTC and the rail-trail movement.

- To access map, photos, reviews and loads of other trip-planning information on the trails mentioned in this article, visit RTC’s free trailfinder website: TrailLink.com.

- Many trails mentioned in this article are part of the National Trails System. Learn more.

- Many of these influential trails have been inducted into the Rail-Trail Hall of Fame. Learn more.

Special acknowledgments: Thank you to Peter Harnik, whose research for the upcoming book, “From Rails to Trails: The Making of America’s Active Transportation Network,” was used for the creation of this article. Special thanks also to Keith Laughlin, Marianne Wesley Fowler and Andrea Ferster for their insights and perspectives on the national rail-trail movement.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.