Washington’s Snoqualmie Valley Trail

Trail of the Month: August 2021

To experience the best of what the Pacific Northwest has to offer, head to the Snoqualmie Valley Trail (SVT). It’s more than a state gem—the trail comes to represent a historical and cultural backbone of western Washington. Considered one of King County’s longest regional trails, the SVT sits neatly between the geographically rich regions of Puget Sound and the Cascade foothills. Located about 30 miles east of Seattle, the nearly 32-mile trail follows the Snoqualmie River downstream and boasts scenes of old-growth forest, mountain ranges and, depending on the season, wildflowers and salmon.

“It’s an alternative form of transportation that’s better for the environment and the health and wellbeing of the people who live here and the people who visit.”

—Caroline Villanova, a community and partnership manager with Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust

“It traverses the most rural and prettiest parts of the county,” said Sujata Goel, a trail administrator who’s worked for King County Parks for the past 14 years.

Ancestral Abundance

Before the trail connected the towns known today as Duvall, Fall City, Carnation, Snoqualmie and North Bend, the Snoqualmie Valley region was home to the Indigenous Coast Salish people since time immemorial.

The Snoqualmie Tribe, for which the region gets its name, was among the largest of the tribes in Puget Sound when the Elliot Bay Treaty was signed in 1855. At that time, they numbered around 4,000 people across Puget Sound and the valley, and their way of life was closely tied to the surrounding ecosystems and nature. So much so that the region is viewed as a spiritual birthplace to their culture. The word “Snoqualmie” or sdukʷalbixʷ in the Native language of Lushootseed, means “moon” or “moon people.”

The Snoqualmie Tribe gained federal recognition in 1999 but was never granted land near their proposed reservation on the Tolt River, between Duvall and Fall City. Today, their reservation sits on 69 acres of land in Snoqualmie.

The Cedar River Watershed Education Center, which is located right off the southern endpoint of the trail at Rattlesnake Lake, delves into the history of the Snoqualmie people and how they lived in harmony with the environment.

The Timber Years

The Snoqualmie Valley Trail exists largely due to the region’s timber industry. As White settlers began to move into the region, many saw potential in the valley’s resources. After the Elliot Bay Treaty was signed, the Snoqualmie Valley became an agricultural and timber hub. The first mill was built in 1872, and by 1877, the Snoqualmie River housed 12 mills.

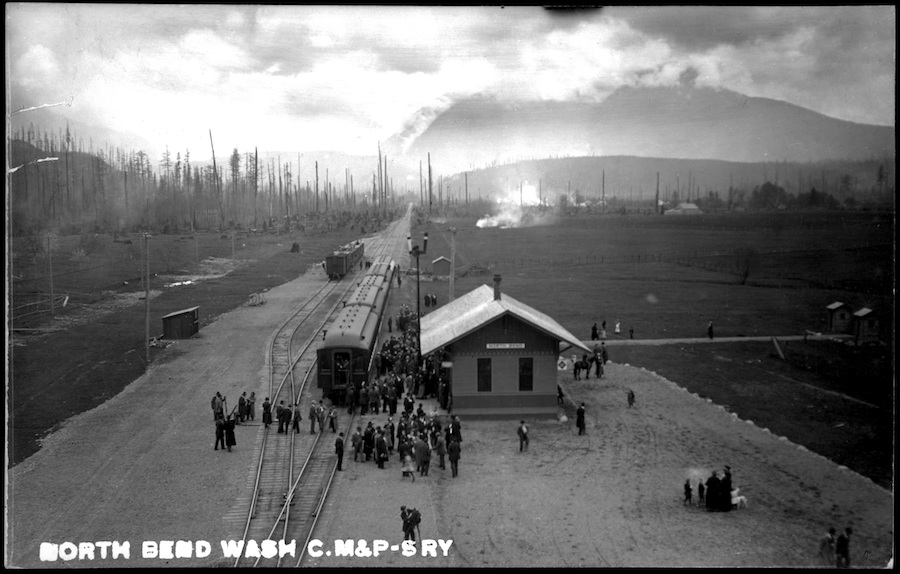

The booming timber industry brought intense competition among railroad companies. In one such case, a years-long lawsuit between two companies ended when one—the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific railroad company (better known as the Milwaukee Road)—was granted permission to construct an extension in the valley. The company finished the spur line in 1911, but, by the 1970s, it was decommissioned. In 1978, King County Parks paid $388,000 for the Milwaukee Road right-of-way, and the trail was partially unveiled to the public in 1990.

The communities along the SVT still pay homage to their railroad past; a collection of historical railway depots and museums can be found in all five towns. In Duvall, Depot Park is home to a railroad depot more than a century old. Other depots include a circa 1890s replica in North Bend and Snoqualmie’s elaborate Victorian-era building, the oldest continuously operating train station in Washington and home to the Northwest Railway Museum. The latter two depots both serve the Snoqualmie Valley Railroad tourism line. Tolt Historical Museum in Carnation is another scholarly stop on the trail if you’re looking for regional history.

This August, the town of Snoqualmie celebrates Railroad Days, their annual community festival that began 82 years ago. Contrary to its name, the event got started to commemorate the arrival of the town’s first fire truck in 1939 but today embodies all things “Trains, Timber, Tradition.” This year the festival returns the weekend of Aug. 28.

Rural Growth in the Valley

Snoqualmie Valley is home to nearly 56,000 residents and, as the region has grown, so too have the activities that surround the three-decades-old trail. Nestled in an agricultural setting, farmers markets and produce stands—such as the Duvall Farmers Market, the Carnation Farms Farmstand and the North Bend Farmers Market—have popped up along the route.

“It’s been a weird, quiet year because of COVID; obviously, a lot of events and festivals and things like that were canceled,” said Katie Egresi, who is a Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust communications coordinator and also helps smaller towns get the word out about their events. “Things are just starting to ramp up with farmers markets, [and] once you get into the towns there’s a lot more to do.”

The towns may be small, but they’re home to art galleries, breweries and walking tours. A complete overview of activities along the trail can be found on a handy map provided by Savor Snoqualmie Valley, a cooperative effort to promote the region’s natural and cultural attractions and activities, coordinated by the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust with local government and community partners.

The Trail Today

The converted rail-trail offers walkers, bicyclists, equestrians and others a “more quiet experience,” according to King County’s Goel, who noted that its proximity to the more urban areas of Washington “provides an opportunity to get away from the city.”

The mostly flat, gravel trail runs parallel to the Snoqualmie River and is dotted with grassy parks and scenic views of the forest and summits surrounding some of the more rural parts of western Washington. Between Duvall and Carnation, there’s the Stillwater Natural Area, which is full of wetlands and pastures. Other highlights include Tolt MacDonald Park (home to a 500-foot suspension bridge over the river), the spectacular 270-foot Snoqualmie Falls and Tanner Landing Park, a popular put-in point for whitewater rafting. During the fall, salmon returning to their spawning grounds can be observed at multiple spots throughout the trail.

“My favorite spot on the trail is Tanner Landing Park; this is a park that signifies what is so great about this trail,” enthused Goel. “Here’s this trail, and all of sudden there’s this beautiful park that presses up against the Snoqualmie River. The trail gives you a really great place to have lunch and affords you the opportunity to go down to the river and dip your toes.”

Once the trail crosses under I-90, catch a glimpse of other summits on the horizon, such as Mailbox Peak. Before you know it, you’ve arrived at one of the trail’s most Instagrammable spots: the Tokul Trestle Bridge. The 100-year-old bridge was renovated in 2016 and sits 400 feet above the creek below. From the bridge, the panoramic view of the valley is dense with mountain ranges painted with evergreen trees.

Once a railroad, now a trail, SVT and its purpose continue to evolve.

“The biggest change in value we are starting to see is communities looking for more walkable nonmotorized mobility,” Goel explained, adding, “You see these communities starting to think about this trail as a real asset and focal point for moving people around.”

The Future of Snoqualmie Valley’s Spine

As the communities around the Snoqualmie Valley Trail have grown, so too have their visions for the trail. At least 80 stakeholders from surrounding communities and jurisdictions are part of the Snoqualmie Valley Outdoor Recreation Action Team. The coalition is represented by different city tourism and parks departments, officials from the state’s Department of Natural Resources and other cities and counties, as well as nonprofits.

At the forefront of the coalition is Caroline Villanova, a community and partnership manager with Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust, an organization that advocates for the region that stretches from the Puget Sound to the Snoqualmie Valley. Together, the group has identified missing links along the SVT in hopes to not only improve the route for visitors but for residents as well. At the top of their list is the push to make the trail a car-free highway.

“One of the important parts of regional trails in general is: Is it an element of transportation?” Villanova posited. “[Let’s] start thinking about how regional trails are a form of transportation itself.”

Although King County does not have visitation data for the SVT, sites along the route are very popular. Snoqualmie Falls, for example—which is easily accessible from the trail—receives 1.5 million visitors a year, according to the Mountains to Sound Greenway Trust.

“Since there is such an increase in visitation in the valley, how can we help current residents and [give them the] opportunity to get around town and connect between towns?” Villanova asked.

While the SVT has lots of connections to other trails, including the more rugged Tolt Pipeline Trail and Little Si Trail, Villanova said the coalition has identified 30 priority missing-link projects. Among them is the proposal to grow the SVT.

“There’s a potential trail connection on the northern end of the trail from Duvall that crosses into Snohomish County and that, in the future, may bring together multiple different county regional trail systems,” she explained. That trail segment, not yet in development, would span 2.8 miles.

The Snoqualmie Valley Trail is also a key part of the Washington segment of the Great American Rail-Trail®, a developing 3,700-mile route across the country. The mega trail will connect 12 states plus Washington, D.C. So far, the Evergreen State’s portion is about 70% complete with 183 miles of missing links to go, including a 7.6-mile gap in Snoqualmie that would connect the SVT to the Preston-Snoqualmie Trail.

Farther south, in Cedar Falls, the SVT currently connects to the Palouse to Cascades State Trail. Although this developing pathway has a few gaps, it already offers more than 200 open miles of trail, making it one of the longest rail-trails in the country; it continues the Great American route across Washington, tying it into Idaho’s trail network at the border.

Related: A New Frontier (Rails To Trails Magazine)

“The SVT is the backbone to the Snoqualmie Valley, and it offers an experience that’s off the beaten path to get out and explore the Valley,” said Villanova. “It serves the purpose of connecting these smaller communities and make it feel like a larger Valley [and] it’s an alternative form of transportation that’s better for the environment and the health and wellbeing of the people who live here and the people who visit.”

Related Links

Trail Facts

Name: Snoqualmie Valley Trail

Used railroad corridor: The Snoqualmie Valley Trail is built on a branch of the Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific Railroad (better known as the Milwaukee Road).

Trail website: King County ParksLength: 31.7 miles

Counties: King

Start point/end point: NE Woodinville-Duvall Road (Duvall) to Rattlesnake Lake at Cedar Falls Road SE (south of Riverbend)

Surface type: Apart from the recently renovated Toluk Creek Trestle (which spans 100 feet) and an on-road detour in Snoqualmie, the trail is primarily crushed gravel.

Grade: The SVT is flat with an elevation gain of 322 from Fall City to Snoqualmie in the middle section of the trail. It is currently not ADA compliant.

Uses: Walking, bicycling, horseback riding, fishing and cross-country skiing

Getting there: The Seattle-Tacoma International Airport (17801 International Blvd., Seattle), which sits about 35 miles west of the trailhead, is the nearest airport. Travelers can head north on I-405 and then east on I-90 to reach the trail. Local King County transit route 629 stops at multiple areas along the SVT.

Access and parking: The trail can be accessed at multiple parks and trailheads across the five cities that the SVT runs through. Parking options from north to south include:

- Duvall Park & Ride (NE Woodinville Duvall Road, Duvall)

- Depot Park (26227 NE Stephens St., Duvall)

- Duvall Park (NE 138th St. and Carnation- Duvall Road NE, Duvall)

- Stillwater Wildlife Recreation Area (off SR 203, Carnation)

- Nick Loutsis Park (32401 Entwistle St., Carnation)

- Tolt MacDonald Park (31020 NE 40th St., Carnation)

- Fall City Community Park (4105 Fall City-Carnation Road SE, Fall City)

- Tokul Road and SE 60th Street (Snoqualmie)

- Meadowbrook Farm (1711 Boalch Ave. NW, North Bend)

- Torguson Park (750 E. North Bend Way, North Bend)

- Tanner Landing Park (North Bend)

- North Bend Park & Ride (331 W. North Bend Way, North Bend)

To navigate the area with an interactive GIS map, and to see more photos, user reviews and ratings, plus loads of other trip-planning information, visit TrailLink.com, RTC’s free trail-finder website.

Rentals: For bike rentals on the SVT’s north end, visit Pacific Bike & Ski (15635 Main St. NE, Duvall; phone: 425.844.0485), located just two blocks from the trail. On the trail’s southern end, Singletrack Cycles (119 W. North Bend Way, North Bend; phone: 425.888.0101) is less than a mile from North Bend’s Torguson Park access point. For rental options for other types of recreational activities, like paddle sports and climbing, check out these venders near the trail: Fall City Floating (4104 Fall City-Carnation Road, Fall City; phone: 844.831.0448) and Pro Ski and Mountain Service (112 W. 2nd St. #856, North Bend.; phone: 425.888.6397 EXT. 1).

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.