Riverfront Resurgence: Pittsburgh’s Three Rivers Heritage Trail

“Is it true you made the Pittsburgh Steelers shorten their practice fields to make room for the trail?” I ask.

Tom Murphy, mayor of Pittsburgh from 1994 to 2006, and the now legendary spearhead of the city’s revitalization in recent decades, doesn’t miss a beat. “Well, that’s the value of being the mayor,” he says. “They didn’t have a choice.”

At the heart of Mayor Murphy’s vision was a burning conviction that the people of Pittsburgh had an inalienable right to access and enjoy the many miles of Allegheny, Ohio and Monongahela riverfront that define their city. A trail system was how he was going to guarantee that access.

So when the city’s NFL team and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center wanted to build a sports science and training complex in the South Side Flats neighborhood that would cut off access to the Monongahela River, Murphy told them they’d have to go back to the drawing board.

“You do what you’re gonna do, but we’re going to have the riverfront,” Murphy said.

To say there was some pushback from the executives would be an understatement. “There was a lot of yelling,” Murphy remembers.

Soon enough, though, the Steelers agreed to shorten their practice fields, and Murphy got his trail.

The Steelers and UPMC were not the only major employers Murphy “encouraged” to rethink their plans to make way for what would become the Three Rivers Heritage Trail; Alcoa and PNC Bank also soon realized that if they wanted to be a part of Murphy’s new Pittsburgh, then the trail was nonnegotiable.

Connecting the Riverfront

Today, the idea that a trail system is a critical piece of infrastructure for a modern city is widely accepted. Back then, it certainly wasn’t. There were many skeptics.

Through this lens, the foresight and courage of Murphy and a small group of trail advocates to commit to the idea of a riverfront trail system is momentous.

The story of how they completely reinvented the role of the riverfront—where the remnants of steel mills and industry lay abandoned and crumbling by the 1980s—actually began when then-Mayor Sophie Masloff was the first leader of Pittsburgh to authorize a strip of land on the Southside for a public trail in 1991. Trail advocates in Pittsburgh were starting to organize, and Masloff’s decision was a key early win. Friends of the Riverfront was formally established in 1991—the group organized cleanups removing tons of trash from the corridor—and formal work on the trail began in 1992 thanks to a $2 million federal grant.

When Murphy took office in 1994, the people whose names would one day be synonymous with blazing the trail in Pittsburgh—John Stephen, Todd Erkel and the late Martin O’Malley, Maxwell King of the Pittsburgh Foundation, and the late John Craig, influential editor of the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette—had the leader in the bully pulpit they needed. Less visible though no less vital was Darla Cravotta, Murphy’s “trails czar” at the city.

Together these early champions did what many thought impossible. It is a gamble that has paid off handsomely. Long gone are the monikers “Smoky City” or “Hell With the Lid Off.” Now, Pittsburgh is routinely listed as one of the best cities in America in which to live and do business, a place where high-tech industries thrive and young people want to be. The 24 miles of multiuse trail along the city’s downtown riverfront is one of the big reasons why.

In this industrial heartland of America—a place so vital in the country’s history over the past 100 years, but still searching, in some cities and towns, for its meaning in the next 100—we are in what feels like a reset of sorts, a crossroads.

“You do what you’re gonna do, but we’re going to have the riverfront.”

—Tom Murphy, Mayor of Pittsburgh, 1994–2006

A Trail System Woven Into Everyday Life

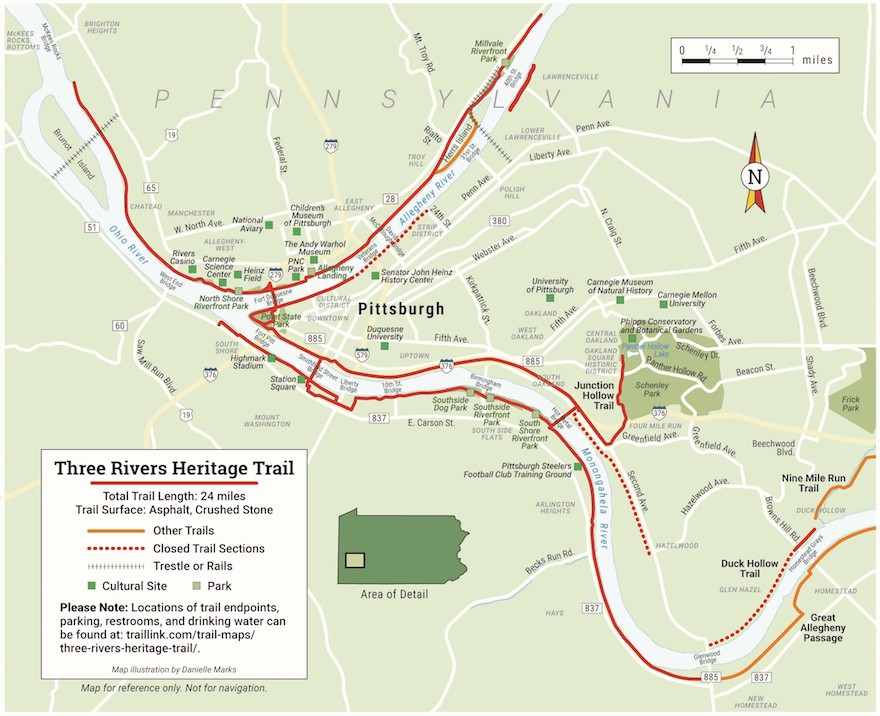

Broadly described, the Three Rivers Heritage Trail follows the Ohio, Allegheny and Monongahela rivers toward their confluence in downtown Pittsburgh and Point State Park at its epicenter. Following the winding vines of these three waterways to the west, north and east, the trail connects people with a vast majority of the city’s attractions and places of interest—from its major sports stadiums, museums and concert venues to the hidden underdogs and future stars of this city’s rising food scene.

To the east, you can follow the Monongahela (the Mon) as far as the tiny community of Duck Hollow, with a diversion along the way into the Oakland Square Historic District and Schenley Park. On this eastern extremity, on the southern bank of the Mon, the connection is made to the 150-mile Great Allegheny Passage.

To the north, the trail passes Washington’s Landing in the Allegheny River before ending just beyond Millvale Riverfront Park. Plans are afoot to extend this section of the trail an additional 26 winding miles up the Allegheny River to the small borough of Freeport (see sidebar).

And to the west, the trail makes it almost as far as the McKees Rocks Bridge before terminating in the largely industrial area of the Marshall-Shadeland, or Brightwood, neighborhood on the northern banks of the Ohio.

The short Duck Hollow and Lawrenceville sections are the only unconnected segments of trail, and therein lies the great strength of the Three Rivers Heritage Trail—its connectivity.

“When I visit Pittsburgh, it is how I get around,” said Eric Oberg, director of trail development for Rails-toTrails Conservancy’s (RTC’s) Midwest Regional Office. “I mainly use it for practical trips. That’s testament to why it’s so great. It really connects to the places you want to be.”

There were 820,000 trips made annually on the Three Rivers Heritage Trail and an $8.3 million estimated impact in 2014.

Particularly for residents and visitors to Pittsburgh unaware of the struggles, conflicts and determined forces that built it, the Three Rivers Heritage Trail seems so obvious. It just makes sense that one should be able to walk, run or ride along the city’s rivers that it it’s inconceivable that there was a time when, barricaded by abandoned mills, razor wire and the detritus of industrial decline, you could not.

In much the same way that the confluence of the rivers at Point State Park is the hub from which the trail system branches out into, and connects, the communities of Pittsburgh, the city itself serves as the hub of the Industrial Heartland Trails Coalition (IHTC) network, a developing system of more than 1,500 miles of shared-use trails through western Pennsylvania, northern West Virginia, eastern Ohio and the southwestern corner of New York.

“Connections to local communities will be a huge priority.”

—Courtney Mahronich Vita, Director of Trail Development, Friends of the Riverfront

It’s a matter of geography (and railroad history), but the metaphor is evocative; just as the rich coal seams, waterways and steel mills made Pittsburgh the beating heart of an industrial boom in the century behind us, it is set now to become the center of a new network, a new industry and a new way of life that may mark the century ahead.

Frank Maguire, the trails and recreation program director for the Pennsylvania Environmental Council (PEC), a leading partner for IHTC along with RTC and the National Park Service, says the story of the Three Rivers Heritage Trail is a rallying cry for the other trail groups in the IHTC, and an inspiration to fledgling trail dreamers everywhere.

The Three Rivers Heritage Trail is at the epicenter of a 1,500-mile trail network effort to reimagine America’s industrial heartland. Learn more at RTC’s partner, the Industrial Heartland Trails Coalition.

“It is a wonderful example for other projects, given the scale of the issues they’ve had to overcome,” he says. “Those groups look at Pittsburgh and think ‘It is possible. Let’s keep beating our heads against the wall for a little while longer, because everything is achievable.’ ”

Expanding The Three Rivers Heritage Trail

Already one of the best urban trail systems in America, the Three Rivers Heritage Trail isn’t done yet. Current trailbuilding efforts are focused on extending the trail an additional 26 miles along the Allegheny River from its current northern terminus outside Millvale to Freeport.

The extension, a mix of on- and off-road sections, will connect the Three Rivers Heritage Trail to the planned 261-mile Erie to Pittsburgh Trail.

As with any good rail-trail project, it’ll be complicated; the corridor passes through a number of municipalities, and ownership of the land is uncertain in some areas. However, a number of municipalities are moving ahead.

Blawnox and Tarentum have already opened on-road sections, and after learning that it already owned the riverfront property needed to build its segment, the borough of Brackenridge is in the design and engineering phase.

The development known as Riverfront 47, currently in design, will include a trail from Sharpsburg to Aspinwall Riverfront Park. Also in design is a trail from Shaler Township to Etna, the new home of Friends of the Riverfront.

“Connections to local communities will be a huge priority,” said Courtney Mahronich Vita, director of trail development for Friends of the Riverfront. For more information about the expansion, visit friendsoftheriverfront.org.

A New Perspective

When Valerie Beichner took over as the new executive director of the nonprofit Friends of the Riverfront (FOTR) at the beginning of this year, she held a series of informal chats over coffee with locals to hear their ideas about the trail, the organization and the community.

FOTR manages and oversees the maintenance and development of the Three Rivers Heritage Trail, supported by a team of more than 1,500 volunteers, in strong and vital partnership with other local organizations including PEC, RiverLife and Allegheny County.

Beichner’s goal was to strengthen the bond that local communities felt to the trail and, in doing so, help foster a sense of ownership, a feeling that the trail is a part of the community.

Beichner said that in response to safety concerns related to opioid use and homelessness that came up during the discussions, FOTR is creating a program to train trail volunteers on how to make decisions about stewardship activities when, for example, they see a needle on the trail or interact with a person who is homeless.

“We feel we have a responsibility to be both good stewards and compassionate human beings simultaneously,” she affirmed.

Beichner is bringing a new and unusual perspective to what the trail can mean to Pittsburgh, and what it can become, with a key goal to make the Three Rivers Heritage Trail a safe and accessible place for all.

There is a growing urgency in Pittsburgh to make sure low-income neighborhoods and people with mobility issues are able to access the Three Rivers Heritage trail and enjoy its benefits.

The “for all” part is particularly important to her. As Pittsburgh continues to grow, the spoils of the city’s prosperity may not be shared equally, and there is a growing urgency among Beichner and her peers to make sure low-income neighborhoods and people with mobility issues, in particular, are able to access the trail and enjoy its many benefits.

Concretely, that looks like wayfinding and signage improvements, ramps and sidewalks in some places, as well as less tangible, but equally important, education and outreach efforts in communities to make sure residents know where the trail is, where it goes and what it can offer.

And early next year, FOTR plans to launch an Augmented Reality mobile app to test tech-friendly ways to help trail users find and access local businesses along the trail—an important step toward sharing the economic benefits of the trail throughout the community.

Just as Tom Murphy was driven by a social consciousness to make the riverfront available to the people of Pittsburgh, Valerie Beichner’s passion for equity and access for all are natural continuations of the mantra that underpins this city’s trail-building history.

Loved by Locals

Her apparent energy for continued improvement and creative reinvention is echoed by the locals I spoke with for this story. All described a favorite memory, or several, of how the trail played a starring role in the ways they enjoyed their home city.

For Jeff Seigler, a planning consultant who moved to Pittsburgh two years ago, that memory was of him and his young son riding together.

“We got off the light rail at Station Square and rode our bikes up to the Hot Metal Bridge, and crossed over. We then rode downtown to The Point, back over the Fort Pitt Bridge and back to the light rail station,” he remembers. “It was awesome; it’s super cool for a kid to be able to bike in the city.”

For Seigler, the trail system was a big part of the reason he moved to the area.

“I wanted to live in a city that I felt was great, that reflected my priorities,” he said. “This is the kind of city where I want to be—where other forms of transportation are available.”

Like Beichner, many locals expressed their love for the trail through their desire to see it improve. Almost all spoke of a need to connect it to more neighborhoods, to more people, and to spread the benefit of a safe walking

“This is the kind of city where I want to be.”

—Jeff Siegler, Pittsburgh resident and trail user

Connection Case Study: Millvale

More than 820,000 trips are made on the Three Rivers Heritage Trail each year, generating an estimated total annual economic impact of $8.3 million in 2014.

That number continues to grow each year. A number of Pittsburgh business executives I spoke with for this story described the trail as an important recruiting tool, and a critical part of Pittsburgh’s ability to attract and retain talented workers.

Inside this frame of economic development, the small community of Millvale, at the trail’s northern extremity along the Allegheny River, is a prime example of how important those connections to and from the trail are.

Millvale local Shawn Lang is the co-proprietor of the Pittsburgh Food Truck Park, which each weekend during the warmer months brings together food trucks from around the area at Millvale Riverfront Park, right on the Three Rivers Heritage Trail.

Millvale is the story of Pittsburgh writ small, one of several old boroughs in and around Pittsburgh that have suffered common pre- and post-industrial fortunes. Now, entrepreneurs of food and drink are part of a small but noticeable resurgence in Millvale, one in which the proximity of the trail plays a key role.

Lang estimates that 25 percent of customers at the food truck park come directly from the trail, in addition to those who learned about the park by passing it on the trail. “The trail was one of the main factors in us choosing that location,” he said.

Lang believes the trail will soon become a strong draw to new residents and the businesses that follow, noting that it is often quicker to ride to downtown Pittsburgh than drive.

If they can only improve that connection.

At present, you can easily ride right past Millvale and never know it was there; the historic business district, including several terrific restaurants and craft brew spots, a short stone’s throw from the trail. And if you do want to ride or walk into Millvale, you have to brave an off-ramp of the busy Pittsburgh-Buffalo Highway.

“The trail is very central to the future of the neighborhood, but it is not as integrated as it should be to the rest of the community,” said Zaheen Hussain, who is working in Millvale on promoting a sustainable, vibrant community. “The trail is a huge opportunity … but the community connectivity piece needs more work.”

If history is any guide, that challenge will not be shirked.

This article was originally published in the Winter 2019 issue of Rails to Trails magazine. It has been posted here in an edited format.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.