Landmark and Legacy: Nebraska’s Chief Standing Bear Trail

Until 2015, Larry Wright Jr. had never walked the abandoned Union Pacific railway that ran alongside the Big Blue River in southeastern Nebraska, a path similar to one his ancestors traveled—against their will and on foot—years prior to the railroad’s completion in the early 1880s.

In the spring of 1877, U.S. Cavalry evicted the Ponca from their home along the Niobrara River in northern Nebraska. It’s a history that Wright, chairman of the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska, knows well.

The order that forced about 700 Ponca to relocate 500 miles from Niobrara to a barren corner of what would become Oklahoma came even after eight Ponca leaders, including Chief Standing Bear, walked for nearly two winter months back home to report that the reservation land they’d viewed in Indian Territory was dangerously unfit for their way of life. Their predictions unfortunately came true.

Arriving too late to plant crops after a journey that led many to succumb to disease and exposure, more than 100 perished in Indian Territory.

“The continuous storms have also caused much annoyance and no little suffering to the Indians, especially to the women and children who were poorly prepared to meet such a condition of the elements,” a U.S. agent said in a letter penned near Beatrice, Nebraska, that June, according to author Joe Starita’s biography of Chief Standing Bear, “I Am a Man.”

Wright visited areas along a 20-mile portion from Beatrice to Barneston.

“I had never been down there before,” Wright said. “To be there and be told that this was the actual land where our people were, I had goose bumps, just imagining our people going through there.”

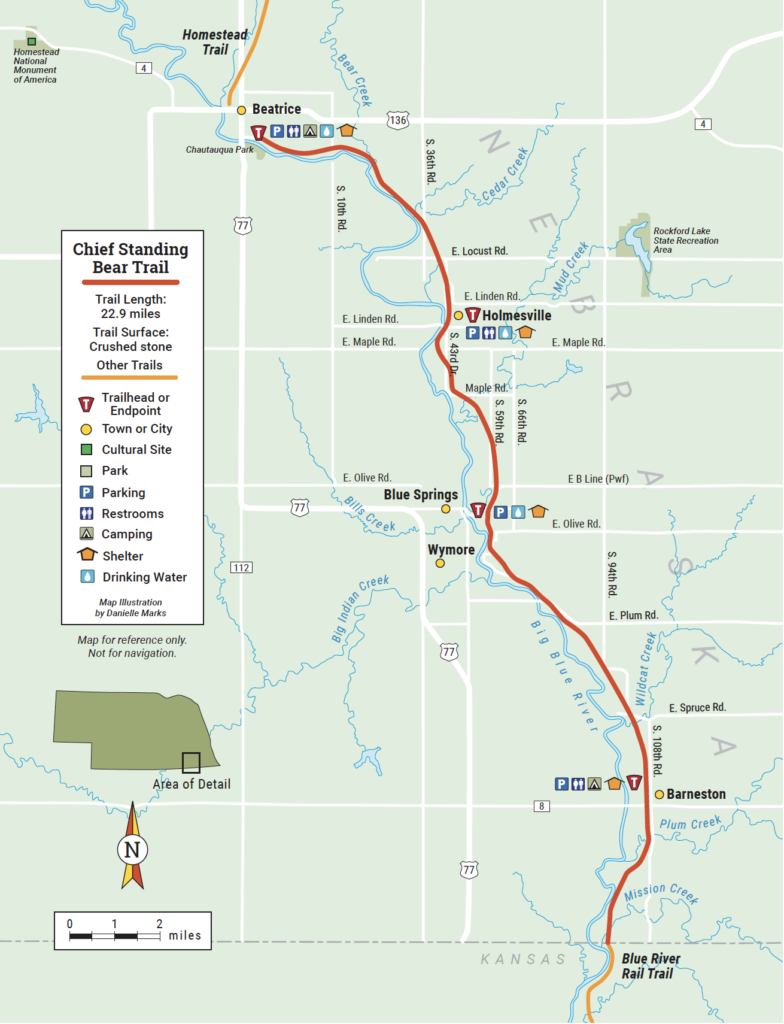

The reason Wright went to see it: The Ponca were going to take ownership of it. The tribe this year officially took possession of the 19.5-mile-long former railway. The 232-acre strip of land, now known as the Chief Standing Bear Trail, completes a nearly 75-mile-long hiking and biking passage from Lincoln to Beatrice to Marysville, Kansas, thanks to the only portion of the Ponca’s path to Oklahoma that has been converted to trail.

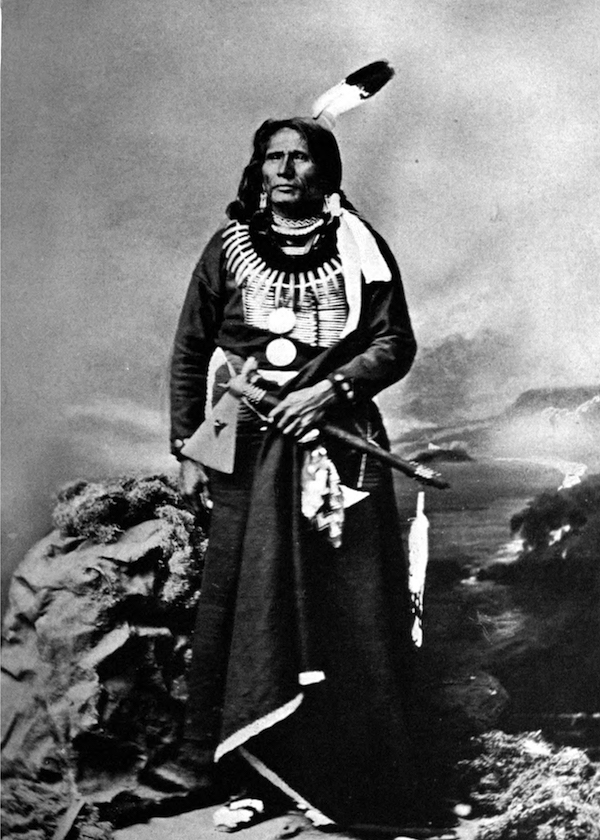

Chief Standing Bear

When Chief Standing Bear and the entire Ponca Tribe were forced to walk south to Indian Country in 1877, his daughter, Prairie Flower, died of tuberculosis within a month of the forced exit. She was buried in Milford, Nebraska. When the tribe arrived in present-day Oklahoma, Standing Bear’s only son, Bear Shield, was one of hundreds who developed malaria and among the third of the Ponca to die from it in the first 18 months in their new home. Standing Bear vowed to his son that he would receive a proper burial in their homeland, even if it meant violating, and then challenging, the law.

Standing Bear and a small group of his followers left the Indian Territory to carry Bear Shield’s remains north, and were arrested in 1879 and held at Fort Omaha. With the help of a newspaper reporter, a pro-bono attorney and a sympathetic general, George Crook, who was also the defendant in the case, Standing Bear sued to prove that a Ponca deserved the rights of a U.S. citizen.

“This hand is not the color of yours, but if I pierce it, I shall feel pain,” Standing Bear said through his interpreter during the two-day landmark federal trial that he won in 1879. “If you pierce your hand, you also feel pain. The blood that will flow from mine will be the same color as yours. I am a man. God made us both.”

A Step in the Right Direction

The Ponca Tribe of Nebraska’s history, Wright said, is one marked by outside efforts to minimize or eradicate the tribe’s identity. Chief Standing Bear, who was arrested after leaving Indian Territory to fulfill a promise to bury his son’s body back home, is known in part for his landmark victory in Omaha’s U.S. District Court. He successfully contested the law that did not consider him a person.

Chief Standing Bear was among a small group of Ponca allowed to return to the Niobrara valley, but the United States officially terminated the tribe in 1966 before recognizing it again in 1990. Not since that year, when a Niobrara farmer returned 26,000 acres to the Ponca, had someone offered to give land to the tribe, Wright said.

Then, in 2015, he heard about a proposal from two longtime coffee buddies in Lincoln, Ross Greathouse and Lynn Lightner. Greathouse, 79, a marathoner and cyclist, is the founder of the Nebraska Trails Foundation (NTF), which purchased the railway corridor running from Lincoln to Marysville shortly after Union Pacific abandoned it in 2000. The railway has been converted to recreational trails over the course of three major projects, the final one being the Chief Standing Bear Trail.

Inspired by a Nebraskan-led effort to get national historic designation for the entire path that Chief Standing Bear and the Ponca walked, Greathouse reached out to Congressman Jeff Fortenberry and Judi gaiashkibos, executive director of the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs, with the possibility of naming the trail in honor of Chief Standing Bear. Both threw their support behind it. Greathouse sought to transfer trail ownership to a natural resources district (NRD), promising nearly $1 million in funds raised for construction and maintenance, but the board for the NRD voted against it.

“We weren’t going to be deterred,” said gaiashkibos, whose grandfather was the last chief of the second rank of the Ponca Tribe. Now a grandparent herself, gaiashkibos has for decades fought for projects like the Chief Standing Bear Trail, which bring a level of statewide visibility to Nebraska’s tribes that previous generations endured without.

The morning after the 2014 NRD vote, Curt Donaldson, a former Lincoln City councilmember, called Greathouse and offered a backup plan.

“He said, ‘Why don’t you give it to the Poncas?’” Greathouse recalled. “The thought had never gone through my silly mind.”

gaiashkibos thought it was a great idea. Wright was initially hesitant.

“My first response, out of habit and history, was, ‘What’s it going to cost us?’” he said. “They said, ‘No, (we’re) going to do it for free.’ I said, ‘Well, nothing ever brought to us is free.’ To their credit, it’s been as promised. From our first meeting with Ross and Lynn talking about this at a coffee shop in Lincoln, their energy and excitement was contagious. That excitement really didn’t build for me until I was actually on the trail.”

The Ponca now partner with the Homestead Conservation and Trails Association, which maintains the trail thanks to $150,000 in funding from NTF and volunteers who want to see the Chief Standing Bear Trail draw more and more visitors.

History and Scenery

The completed trail runs 22.9 miles from downtown Beatrice, which maintains the first few miles out of town, to the Nebraska-Kansas border, just south of Barneston. After a few blocks of paved city pathway, the trail transitions to crushed limestone, which takes cyclists and hikers under canopies of trees and bisects rolling farmland before the path dips back beneath trees and re-emerges among native prairie grasses, again and again. During a late-May ride, more than one meadowlark, Nebraska’s state bird, scurried across the limestone before sailing off with flights of swallows flushed from the prairie grass as I passed.

“It’s just super long, super straight, and those are fun rides,” said Jacob Olsufka, an avid cyclist and also the Ponca Tribe’s director of finance.

The tree-covered portions are welcome respite once the prairie winds get going.

“That’s our mountain,” said Colleen Schoneweis, who six years ago founded the Beatrice-based Big Blue Biking Club and sits on the Homestead Conservation Board. “The wind is our mountain.”

Sixteen re-decked bridges connect the trail, thanks in part to Lightner, an engineer who renewed his license and came out of retirement to finish the project. The path often runs up alongside the Big Blue River, which grows ever more visible from the Chief Standing Bear Trail once autumn arrives.

“About every mile or 2 miles you hit one of those points, and the river’s right there,” Greathouse said. “And when you get into Kansas, the river’s there all the time. To ride it all the way to Marysville is a real blessing.”

“Very scenic,” said Hal Smith, a Lincoln veterinarian who was biking from Marysville to Cortland with a stop in Beatrice for lunch, where we chatted. “You’re going to enjoy the ride.”

He and four other friends were on their way back home from “credit card camping”—their words—staying overnight at the Marysville Surf Motel. (Some cyclists have taken to calling and reserving rooms from the 11.7-mile Blue River Rail Trail, which connects to the Chief Standing Bear Trail, said hotel manager, Smita Patel. “They can park inside the rooms,” she said.) Smith said they had burgers at Marysville’s Landoll Lanes that night and swung through Barneston’s Grand Avenue Bar and Grill on the return trip. Servers at both establishments said they’re growing accustomed to filling up water bottles.

“It’s awesome,” Smith said. “You can start at Haymarket Park [home of the University of Nebraska’s baseball team] and go all the way to Marysville if you want.”

Trailheads in Beatrice, Holmesville, Blue Springs and Barneston offer shelter and bathrooms but also signage featuring histories of the area, including information about local wildlife, pioneers and the Ponca.

Experience the beauty of Chief Standing Bear Trail

Nebraska historian Jan Eloise Morris said she spent four months researching the pieces that are installed upon the walls at the Blue Springs shelter, which is but one example of the attention to detail that volunteers have given to the rest stop near a 320-person village. There are already 67 bluebird boxes along a 5-mile trail corridor near the shelter, said Dean Cole, a volunteer active at the Blue Springs trailhead. He said in June there were many more projects on the way, including the installation of a medicine wheel adhering to Ponca specification and the planting of rare native species— hickory, black oak and sweetgum trees, among them—at a community arboretum. Aspects from four landscape design submissions from students at a Lincoln community college are being melded into the final plan, which a $6,000 Gage County Foundation grant is helping to fund.

“The trail’s for everyone … and this tragic story has somewhat of a more celebratory ending.”

– Judi gaiashkibos, Executive Director, Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs

Wright said that seeing the collaborative effort building along the trail has reinforced the belief that the decision to take ownership of the trail was the right one.

He stated, “To know that there’s a piece of our history that we’re forever tied to, to have title to it and know that people use it for recreation and will learn a bit of our history as well—a tragic event that tried to get rid of our tribe from Nebraska, but ultimately is still a recognition of [the fact that] we’re still here—it kind of brings it all full circle, and that’s a good feeling to have.”

Working Together to Bless the Trail

The deed for the Chief Standing Bear Trail was officially signed over to the Ponca on May 11, 2017, at a ceremony in Barneston that not only signified the conclusion of the transfer but also the completion of a retracing of ancestral steps that began on April 29 in Niobrara. There, dozens of members of the Ponca Tribe set out in cold rain to follow the path of the Ponca’s Trail of Tears. In all, 263 tribal members registered to participate in all or a portion of the walk over its 12-day duration.

gaiashkibos said she hopes the trail draws many more out to use it now that it’s open.

“I just encourage everybody to get out there and get out on the trail and exercise and be healthy and look at life in a holistic way and open their minds to living together in harmony,” gaiashkibos said. “The trail’s for everyone, and the Ponca people were an important part of Nebraska’s history, and this tragic story has somewhat of a more celebratory ending. We hope the future holds more things like this.”

On the final day, Ponca Tribe of Nebraska members joined together with members of the southern Ponca Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma and Otoe, who participated in the festivities, performed traditional dances and dined on traditional cuisine provided by Schoneweis, who runs a catering business and offered to make fry bread and stew with recipes provided by the Ponca cultural director. This being Nebraska, no one seemed to mind that she subbed beef for buffalo meat in the hominy stew.

This article was originally published in the Fall 2017 issue of Rails to trails magazine. It has been reposted here in an edited format.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.