The Road to a Thousand Wonders

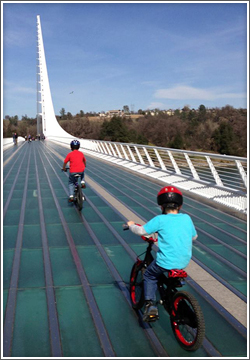

The astonishing Sundial Bridge peeks out from a tall canopy of cottonwood trees as I approach Redding, Calif., on Highway 44. It looks like an enormous white harp or an egret. Designed by Spanish architect and engineer Santiago Calatrava, the eight-year-old bridge radiates over the lush green landscape, linking both sides of the Upper Sacramento River where it makes a wide turn at Turtle Bay. Unlike some of the region’s other manmade marvels, the bridge doesn’t touch the waterway or its precious runs of salmon and steelhead. The tall pylon is the world’s largest sundial and doubles as a support column for the steel cables that suspend the 700-foot structure over the frigid waters of the Upper Sac.

The bridge sits next to Turtle Bay Exploration Park, a 300-acre complex dedicated to discovering the river’s rich history, and featuring a museum, aquarium, arboretum, and botanical gardens. The bridge, park and Redding’s vast network of trails – built in phases over the past three decades – have helped this once-thriving rail hub restore its identity. What were once neglected rail beds and trash-strewn mining roads have been transformed into world-class trails where Olympic athletes train and locals come to spend time outdoors.

“Our citizens here are as proud of the trails as they are of anything,” says Mike Warren, a former Redding city manager and now CEO of Turtle Bay Exploration Park. “People who come into our community are amazed, simply amazed, that a community our size [population 100,000] has this many and this quality of trails.”

“Our citizens here are as proud of the trails as they are of anything,” says Mike Warren, a former Redding city manager and now CEO of Turtle Bay Exploration Park. “People who come into our community are amazed, simply amazed, that a community our size [population 100,000] has this many and this quality of trails.”

“It’s a real social scene, and Redding’s gotten healthier [as a result],” says Laurie Schell, who’s out enjoying the trails on a beautiful spring Saturday in late March.

Redding’s name comes from Benjamin Barnard Redding, a politician and land agent for the Central Pacific Railroad. The company built the western transcontinental railroad, which came through here, and christened the town in his honor when it was founded in 1887. It is home to one of the most photographed peaks in the world, the snow-capped wonder known as Mount Shasta. To the east is the gem of the cascades, Mount Lassen, a dome volcano that last erupted in 1915. To the west sits Mount Balley, a popular mountain biking area that overlooks Whiskeytown National Recreation Area. These stunning vistas of the Cascade and Trinity mountains surround Redding, the gateway to the Sacramento River Trail system.

It’s almost noon when I arrive with my bike at the Sundial Bridge. The shadow of the bridge is about to touch one of the ceramic tile markers in the round, clocklike plaza that lies beneath the gnomon.

Though much loved now, Schell says there was some vocal opposition to the bridge when it was first proposed. The head of the local farm bureau told a New York Times reporter it was “the epitome of waste.” And how does this conservative community feel about it now? “I think they’ve come around, because it’s the center of so much,” Schell says. “It’s family-friendly, and for the older set it just is a peaceful place to visit.”

“I love it here,” says Heather Phillips, as she tosses a ball to her three-year-old son, Zander, who swings a bright green bat but misses. Phillips lived in Redding as a kid and moved back as a young adult.

Redding Revival

Redding is the largest city between Sacramento and the Oregon border. For folks passing through on Interstate 5, it has been considered mostly a stopover to fill up the tank and grab a bite to eat. Until recently it was “built with its back to the river,” says Terry Hanson, a semi-retired Redding community projects manager who, along with a small group of dedicated trail advocates, played a significant role in getting the trails funded and built. “No one enjoyed the river or used the river very often because it was not integrated into the fabric of the community.”

Unlike the people who first inhabited this area and considered the river sacred, those who came in search of gold and other valuable minerals poisoned the water and land, leaving a legacy of toxic waste. The Upper Sacramento River is still recovering from years of hydraulic mining and excavations. For a long time, residents viewed the river primarily as an industrial resource, which explains why so many had turned a cold shoulder.

Now, Redding’s increasingly popular trails, combined with restoration efforts, have brought renewed appreciation for the town’s riverfront splendor. People come to enjoy the trails on foot, bikes, skates, and horseback. There are a total of 226 miles of paved, dirt and single-track trails, with spurs that connect to almost every neighborhood, providing arteries to work, play, and take in this bounty of natural treasures.

“I think it’s transformed the town,” said Steve Anderson, former head of the federal Bureau of Land Management (BLM) in Redding, and a stalwart trail advocate. “House boating on Lake Shasta was always the thing to do in the summertime. Now [with the trails] what you’re seeing is, ‘Wait a minute, this is a great place to be in the spring, this a great place to be in the fall, and this is a great place to be in the winter.'”

As a result, more people in Redding are biking and walking. A recent study by Healthy Shasta, a local partnership formed to promote healthy and active living among north state residents, found that 62 percent of locals bike and walk for recreation more often since the critical Dana to Downtown trail extension was built along Highway 44 in 2010.

That extension “was really the first decent non-motorized link between west Redding and east Redding,” says Healthy Shasta’s Amy Pendergast. “It crosses the Sacramento River and I-5 safely and pleasantly.” Redding has also seen a reduction in vehicle miles traveled in recent years, and bicycle counts are up on city streets, all spurred by a greater interest in the trails.

The idea to create what is now the Sacramento River Rail Trail had been talked about for decades. A rail-trail study was completed in 1990 with support from the McConnell Foundation, which has funded a lot of trail building here. The study sat on the shelf until 2000. That’s when Kuntz arrived in Redding. He came from the BLM’s Susanville office, where he had worked on the Bizz Johnson Trail – “one of the mothers or fathers of the rail-trail system,” he says. At the time, most of the ballast and rock that held the Redding corridor’s rails and ties in place had been removed. What remained was mostly a rocky undulated path littered with garbage and washed out in some places. Only off-road vehicle enthusiasts ventured there.

All that has changed now. The mostly flat 16-mile Sacramento River Trail begins at the Sundial Bridge and follows the path of an old mining road on the north banks to Keswick Dam. On the south side of the river, the trail runs from the historic Diestelhorst Bridge before turning into the Sacramento River Rail Trail at Keswick Reservoir. The rail-trail then proceeds for 10.7 miles on original railbed, except for a two-mile stretch that winds through rolling hills above the reservoir. It then descends onto the banks of the reservoir and onto Shasta Dam. I’ll be pedaling this 19-mile journey.

Journey of Marvels

The Sundial Bridge extends over the Upper Sac at the start of a large bend, where the river becomes shallow over a wide floodplain, collecting gravel, minerals, and other sediment. Centuries ago the Wintu people built huge villages around the river’s curve, netting an unending harvest of Chinook salmon and mussels.

In the mid-1800s gold miners decimated the Wintu, as well as this part of the river and the surrounding land. The area later was occupied by a sawmill and then a gravel factory that played a key role in construction of Shasta Dam in the 1930s and 40s. The factory, known as the Kutras Aggregate Plant, began years of excavation on the site. What’s left of the factory’s main processing building sits at the entrance to Turtle Bay Park, next to the Redding Convention Center, a crumbling but treasured building that locals call “The Monolith.”

West of the bridge, Phillips and her son lead me to the Arboretum Loop, a 1995 river trail section that circles 200 acres of savanna oak and wetlands. It’s called the McConnell Arboretum in honor of the late Carl and Leah McConnell, whose endowment has supported the river’s preservation and restoration.

As I bike through the botanical gardens, swallowtail butterflies appear. They thrive in jungle-like areas along the river, where wild grape vines wrap around trees. Here they flit about the reddish-purple flowers of redbud trees. Along the trail I’ll see a wide variety of wildflowers, mostly purplish lupine and yellow buttercup. Redbud is everywhere along the trail here as it flows toward a lovely water sculpture, with a spring carved out of green marble.

The botanical gardens span 20 acres, encompassing a separate butterfly garden, a Mediterranean climate garden, a garden for children, and a medicinal garden. It’s a favorite place for Phillips; she’s on the trail here with her family at least three days a week.

“The trail has helped me to kind of slow down and be comfortable living my life without a car,” she says. As we continue pedaling, passersby offer smiles and hellos. “If I didn’t have the trail I don’t know if I would even be riding a bicycle, because I may have been uncomfortable with the idea of riding with traffic.”

Several hundred feet west of the gardens we join the main river trail again and meet up with Jeff and Anne Thomas. Local bike advocates, they run Shasta Living Streets, an organization that hosts open streets events and is working to build support for safe bikeways on city streets. “The trails are opening up people’s minds to that,” explains Anne Thomas. “People get out on the trails and realize how much they enjoy it. Later they think, ‘I just have a short errand to do and I’d like to do it on my bike.'”

She points out that, in addition to drawing 750,000 visitors every year, the trails now are the route of choice for many bicycle commuters. That picturesque ride to the office is one reason people looking to escape high rent and stressful lifestyles in the Bay Area or Southern California are relocating to Redding.

“If you had asked me if I wanted to move to Redding 10 years ago I’d say, ‘No way. Forget about it,'” says John Eliot, who moved with his family from San Diego to the Redding area in 2007. He takes the popular Middle Creek Trail from the historic town of Old Shasta to the river trail to commute to his acupuncture practice. “As a young professional, I like being out in nature and it’s what attracted me to Redding.”

We’re on the part of river trail that was the first mile to be constructed in 1983. Before that, the old mining road was strewn with trash, and homeless camps were common. I find it easy to slow to a snail’s pace on my bike without worrying. People are cool and the trail is smooth. Up ahead, several anglers are a little more than knee-deep in the river, vying for Redding’s well-known stock of native rainbow trout and steelhead.

Soon we pass a seasonally erected diversion dam that extends across the river at Caldwell Park, home of the Redding Aquatic Center. Built in 1916, the dam steers water into a canal system every spring through fall, routing it to farmland south of Redding. It contains two fish ladders to help push salmon and other fish upstream as they make their final journey home. When this spectacle happens, visitors can take a peek underwater by stepping down to a glass viewing area just off the trail.

Several hundred feet up the trail, a stunning piece of railroad history comes into view: a 70-year-old rail trestle built by the American Bridge Company when a 26-mile chunk of the Central Pacific Railroad was diverted for construction of Shasta Dam. The truss bridge, with its rusty triangular components below the deck, is still used by Union Pacific and Amtrak, and stretches almost a mile over the river.

The Shasta Route

The railroad used to wind through the canyon as part of the Southern Pacific Railroad’s California-Oregon line, which was marketed in the early 1900s as “The Road to a Thousand Wonders.” The segment from Gerber, Calif., 40 miles south of Redding, to Ashland, Ore., was known as the Shasta Route. I wonder what it must have been like for passengers traveling in ornate wooden rail cars. At the time, there was an abundance of resorts, the most popular being the world-renowned Shasta Springs, at the base of Mt. Shasta, where guests got to sip its famous sparkling water. Among the regulars were Mae West, Jimmy Dorsey, Lena Horn, and Cary Grant.

Just beyond the trestle, we approach Lake Redding Bridge and the historic Diestelhorst Bridge. Built in 1915, the Diestelhorst was the first highway bridge to cross the river, and at that time the only way into Redding from both north and south. In the 1990s, with the popularity of the river trail growing, the Redding City Council decided to make it a biking and walking bridge, providing a critical link to the rail trail on the south side of the river. The Diestelhorst was closed to cars in 1997. Now the Lake Redding Bridge accommodates automobiles – as the plaque reads, “in order to retain the historic Diestelhorst Bridge as a pedestrian crossing, and to provide a new state of the art bridge for present and future generations.”

The Diestelhorst is a particularly magical spot for Phillips, because this is where she got married. “I think it’s just gorgeous at sunset, with the western mountain range right there,” she says.

At this juncture, trail users can choose to continue west on the north side. This stretch from the Lake Redding Estates subdivision to Harlan Drive and upstream to a spectacular stress-ribbon bridge was the second phase of the river trail, built in 1985. As Hanson recalls, it wasn’t easy, mostly because the developer of a local housing estate was fiercely opposed to providing an easement. But as local journalist Paul Shigley writes, “The city stood tough and somewhat unwittingly birthed the riverfront trail system that has become one of the community’s greatest assets.”

We make our way back from the Diestelhorst Bridge on the south side of the river, following the trail as it winds along original railbed. Initially a crushed granite path, the corridor was paved in 2010. A small, jungle-like forest huddles next to the trail to our right. As we pedal up the trail, the river changes color. No longer turbulent, it turns from blue to greenish, reflecting the rich green habitat along the banks. In the waters one might spot river otters, muskrats, and elusive beaver hauling mud and sticks to build dams in the tributaries. Trail regulars occasionally see a black bear or a mountain lion. Sometimes they encounter skunks, garter snakes, and gopher snakes. Rattlesnakes aren’t awake in late March, but will soon emerge.

This time of year is spectacular for bird watching. On a typical spring day you’re likely to see an abundance of migratory birds from Latin America, including the yellow warbler and the yellow-breasted chad. Quail frequent the trail. Canada geese are prevalent throughout the region, along with mallards and mergansers. Bald and gold eagles can be spotted. Woodpeckers such as the red-breasted sapsucker are common in foothill pine trees. In the wintertime thousands of robins fill the skies.

Past historic Middle Creek Road, where another paved trail goes to Old Shasta, I see what looks like a trailer park. A plaque identifies this as the former site of the 1883 Waugh Hotel, which closed in the 1920s. A few mobile homes sit on the site now and nothing remains of the hotel. Middle Creek Road itself was built when the Central Pacific Railroad tracks were laid. “Travel was slow and arduous in those days of horse-drawn vehicles and wood-burning locomotives, and frequent two-way stops were necessary,” the plaque reads. Hence the hotel. A Wells Fargo messenger was brought to the hotel after being fatally shot in a stagecoach holdup on May 14, 1892. The perpetrators, Charlie and John Ruggles, “were lynched by the railroad tracks in downtown Redding by a mob that broke into the county jail.”

Farther up the trail, desert-like rocky grasslands line the river. Mount Balley graces the western skyline. I spot a suspension bridge ahead, which takes trail users to the southern side of the river, forming a loop popular with locals that leads back to the Sundial Bridge. This is the spectacular Sacramento River Trail Bridge, a 420-foot long, 13-foot-wide, stress-ribbon concrete structure. Its cables are deeply anchored in solid granite. Built in 20-foot segments over two years and completed in 1990, it was the first of its kind in North America. I ride onto the bridge’s deck and take in the view. I see Keswick Dam up ahead, the next leg of my journey.

The dam was built in 1950 to help regulate releases from Shasta Dam. Beyond it, the trail begins to get a little difficult, even for an experienced hill climber from San Francisco. This is where many locals turn around and head back. Mountain bikers can cross to the north side of the river to access an extensive system of unpaved trails, including the upper and lower Sacramento Ditch trails.

At Keswick Dam Road I reach the base of what is aptly called Heart Rate Hill. This is the trailhead for the Sacramento River Rail Trail, and the road is the only one I’ll cross on my ride. “Dear Trail User,” a Heart Rate Hill sign reads, “this slope in front of you can be used to determine your heart health. The same protocols used in a doctor’s office treadmill are here. Take your pulse. Make careful note of the time and seconds. Walk or run the hill to the next sign.”

As I climb the hill, with the sun pouring down, I break into a sweat and start breathing more heavily. Locals call this portion of the trail the roller coaster. It gets steeper as I pedal on. Signs warn bicyclists to proceed slowly on the descents. The trail rises above the river, which turns into Keswick Reservoir beyond the dam. Here I get a breathtaking view of the vast river canyon below.

Heart Rate Hill

A fork in the rail-trail at the top of Heart Rate Hill leads to a spectacular viewing area built by the local Rotary Club. “We didn’t have any money for it and they came to us and said ‘Hey, that’s a great spot; we’ll do the work for you,'” explains trailblazing advocate Bill Kuntz, who works in the local BLM office. That community spirit is typical of how the river-trail was built: volunteers and even prison inmates from the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection pulling together to turn an abandoned rail bed into the magnificent rail trail it is today.

After the roller coaster section, the trail winds down around rock and grass to hug the reservoir’s banks. Westward is Iron Mountain, where miners “once pulled iron, silver, copper, zinc and pyrite,” a BLM brochure explains. It now is a superfund site, and the culprit for so much of the river’s degradation. Restoration funds were used to build the rail-trail.

Shasta Dam, the end of my ride, is not far from here, but just pass Motion Creek is another prominent piece of rail history: a 500-foot-long rail tunnel, once abandoned and marked with graffiti but now part of the rail-trail. Afternoon sunshine lights the way through the tunnel, except for a blink of darkness as it curves. A flock of turkey vultures circles above when I emerge.

The rail-trail ends at Coram Road, which ascends to the top of Shasta Dam. I’m out of breath and tired when I reach the road. To my left is the Chappie-Shasta Off-Highway Vehicle Area, a 52,000-acre expanse that offers 200 miles of roads and trails. Shasta Dam towers 600 feet above me. It’s a steep climb to the top, but I continue without stopping, motivated by the view that awaits.

I’m not disappointed. From atop the dam, the view is simply incredible. To the north sprawls an endless lake, with Mt. Shasta reigning above. To the south lies a spectacular canyon, “The Road to a Thousand Wonders.”

For Kuntz, the trails are not only about rediscovering the river, or the rich history of the area, but also about getting people off their couches. There is a deep sense of accomplishment for him and others who worked tirelessly to build this remarkable trail system.

“I meet so many people, especially mothers with their kids and other women, who didn’t have much opportunity to go out and use trails around here,” says Kuntz. “Some of them have lost 20 pounds, 30 pounds, and they’ll come up to me and shake my hand and say ‘Thank you for your trails. They saved my life.'”

This feature first appeared in the Fall 2013 edition of Rails to Trails magazine. Due to space restraints, we had to edit the original down quite a bit, so we’re pleased to present the uncut story with many additional travel facts and descriptions. One of many perks provided when you become an RTC member, our quarterly magazine includes lots of great stories like this.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.