History Happened Here: Sidepaths and the Persistent Dreams of Trail Building

As we close out Bike Month, we’re pleased to run this guest blog exploring the history of bike paths in America by Dr. James Longhurst, associate history professor at the University of Wisconsin – La Crosse.

Right now, in the middle of the 21st-century bike boom, the rail-trail movement is the most successful way to build trails for bikers and walkers. But it’s certainly not the first; many other plans for trail building have come and gone.

Bicyclists were looking for places to ride just as soon as the high wheel appeared in America. Particularly when the easily mastered “safety” bicycle became widely available in the 1890s, cyclists built separate trails for their own use. These riders weren’t yet trying to get off the road—automobile traffic did not yet exist—but were instead dealing with two 19th-century problems. First, roads outside of cities were unpaved and haphazardly engineered, impassable in bad weather and rutted in good weather. Second, there were very few roads overall.

The first successful idea was for cyclists to build paths on their own through club membership or contributions. These were generally recreational trails that connected cities to nearby lakes or tourist attractions; they cut through fields and forests and didn’t necessarily follow existing roads. For example, in 1895, Chicago cyclists proposed “a sort of bridle path, such as is provided for equestrians, except of course with a different surface” in their parks.

But the bike boom soon overwhelmed voluntary cycle-path building, leading one cyclist to propose in 1897 a far reaching-plan “to induce railway companies to build cycle paths along their rights of way. They could be built of cinders, at small expense to the companies, and easily maintained.” The benefits of building alongside railroad tracks were numerous: “Good riding surface, absence of grades; direct connections between points; stations and mile posts would show distances…frequent wagon-road crossings would afford connections in all directions…” and more. But this idea wouldn’t take hold for almost a century; 19th-century railroads weren’t known for their charity, no matter how small the expense.

By 1897, riders in upstate New York came up with another new idea called a “sidepath.” They proposed a separate, bicycle-specific network of paths, paved and maintained by the sale of legally required sidepath tags, and enabled by state laws creating county commissions. Like sidewalks, sidepaths would be built alongside existing roads, in the existing right-of-way. The New York cities of Rochester and Niagara, as well as Minnesota’s Minneapolis and St. Paul, each built hundreds of miles of these hard-surfaced paths.

RELATED: History Happened Here: The Minuteman Bikeway (A Revolution on Two Wheels)

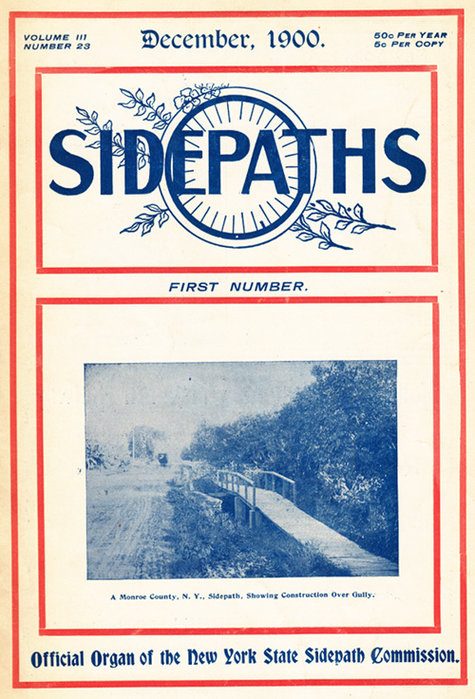

Still, there were complications: States that tried to build sidepaths through taxes rather than tag sales ran into legal and political opposition, and the national League of American Wheelmen (LAW) originally had mixed feelings about separate paths undermining their support for paving new roads. But by the turn of the century, states and cities across the nation had built successful networks, which were chronicled in the popular press and Sidepaths, the magazine of the movement. Journalists were dreaming of a transnational network of bicycle-only paths stretching uninterrupted “from New York to Buffalo and between Detroit, Chicago, Milwaukee and Minneapolis,” thus creating a “transcontinental highway” of sidepaths, putting Europe to shame and making the United States “pre-eminently the country for tourists.” By 1900, even the LAW was convinced; one league publication predicted that “within five years, this country will possess a system of sidepaths that will extend almost everywhere.”

But the sidepath movement died out as quickly as it appeared. The bike boom itself was fading, and the legislative successes of the Good Roads movement seemed to make sidepaths unnecessary. These new, taxpayer-funded roads paved over sidepaths where they had been built. Cyclists weren’t overly concerned; without significant automobile traffic, the new roads seemed to be a dream come true.

Still, as cars became more numerous throughout the 20th century, cyclists and hikers kept returning to ideas for separate trails. Some advocates were calling these “bikeways.” By 1964, Secretary Stewart Udall’s Department of the Interior was promoting trails, paths, lanes and routes under that catch-all term. The next year, Udall commissioned the study that would eventually produce the Trails for America report, calling for new hiking trails and bikeways. “To avoid crossing motor vehicle traffic,” said the report, “bikeways would be located along landscaped shoulder areas on frontage roads next to freeways and expressways, along shorelines, and on abandoned railroad rights-of-way,” or “along quiet back streets and alleys.” It was a fine idea, but there wasn’t a lot of federal money available. While some bikeways were built, it wasn’t until later decades that “rail-trails” emerged out of the list of suggested bikeway locations as the more successful model.

Remembering some of this forgotten history might help us treasure the success of rail-trails but also remind us of backup plans and alternatives. It’s clear that money and politics can endanger these visions—but also that the power of persistent dreams keeps driving innovative plans for trails.

Donate

Everyone deserves access to safe ways to walk, bike, and be active outdoors.